There is no political analyst or policymaker who in the past few years would not have characterized the level of the present state of the US-Russian relations as the lowest since the end of the Cold War. Essentially, this is an accurate assessment of where things stand as of today. Yet, this framing barely gives a sense of the magnitude of the problem and its implications for the two states and the rest of the world. The relations between Russia and the United States as they used to be throughout the Cold War and later in the post-Soviet era are over. No matter whether the present situation has arisen from a single crisis or erupted as a result of gradual crumbling of the system designed in the past, what has truly made the relations suffer is the erosion of their two fundamental pillars – the principles and the agenda. The formerhasserved as a support skeleton forthe interaction between the two powers since the end of the World War II (WWII) (1939-1945). The agenda served as flesh of the relationship that eventually made the two arch enemies maintain contact despite their bitter disagreements on how the world should look like. Both the principles and the agenda thus used to define the relationship for over seventy years. Both dramatically changed some time ago, even if the thinking about them largely persists.

The Cold War paradigm revisited

The Cold War is frequently referred to as a benchmark of the US-Russia relations[1]. Yet, today’s situation gives a sense that it is rather misleading. Contemporary Russian discourse tends to use the term Сold War primarily in three contexts:

- to refer to a historical period that shaped the international system for the most of the 20th century;

- as a catchphrase for contemporary US-Russia confrontation;

- to describe the situation when amidst serious ideological disagreements the great powers would still abide by certain, though unspoken, rules of the game.

The last point is especially sensitive to most senior Russian decision-makers and larger political community. In a number of occasions, the Cold War is counterintuitively portrayed as a gold standard that the contemporary great power rivalry should seek to reproduce should it find ways to avoid a disastrous nuclear war. The problem with such a vision today is that both the intentions of the actors and the structural factors of the rivalry are different.

Modern world is more complex and intertwined than it used to be between 1946 and 1991. Today’s Russia is no Soviet Union. Its resources are more modest, the scope of its global ambition is narrower, and unlike the USSR, Russia promotes no particular ideology in the world arena. An autocratic character of Putin’s governance – as it has come to be portrayed in the West – and Moscow’s inclination towards promotion of conservative values offer some competitive advantages for Russia in international politics. Yet, they do not make up for the lack of ideology in modern Russia neither even pass for one, albeit they are often perceived that way by outsiders.

Unlike the Cold War era, there is today a great asymmetry between the US and Russia in terms of what they each want from the world and from one another. The United States seeks to preserve its declining – yet still dominant – position against rising China. Russia, meanwhile, does not seek to establish dominance in the world, nor does Moscow seek to prove that its socio-political formation is a more efficient development model than that of the US, as it did during the Cold War. This is China’s approach. Rather, deceived by the West in the 1990s and mistreated in the 2000s, Moscow has embarked on de-Westernization of the international system, even if Russia still occasionally attempts to engage with that system on its own terms.

As a result, in Russian political discourse the idea of a multipolar world – the term coined in the mid-1990s – has come to represent the ideal of a just and inclusive system that would be more responsive to Russia’s national interests. In the policy-making community the concept of a multipolar world occasionally clashes with the proposition that a world with multiple power centers may be a lot more chaotic and is unlikely to be any friendlier to Russia. Yet, the dissatisfaction with the existing US-dominated system prevails over the concerns about what a multipolar world might bring. This makes one conclude that the concept of multipolarity is rather a euphemism for post-American or even less-American world, a general direction in which, according to Russian views the world is and should be going, but not a final destination for the world system. Bluntly put, Russia does not in fact envision the system it eventually seeks to construct, but it does know what system it seeks to deconstruct.

There are other narratives outside the Cold War framework that relate to the historic period but offer a slightly different understanding of the present character of the relationship. One of them argues that Russia and the US are somewhat predestined foes[2]. This vision suggests that Russia and the United States have never really been true partners in the post-Cold War era, and they usually criticize the very debate over the crisis of partnership. This narrative may not be representative of the academic and expert community but is supported by various political commentators, talking heads, and journalists[3]. Moreover, this narrative suggests that Russia and the United States by nature have irreconcilable interests in some of the world’s key regions and that their policies cannot be married. This narrative is in many ways appealing to uninformed public which makes it easier for the authorities to embark on a more anti-Western/Russian policy.

Another narrative, call it the narrative of the new normal, insists that what is happening now in the US-Russia relations should not create a doomed vision of the future. It pictures the relationship as something where the cycles of confrontation are replaced by the cycles of resets and again by the cycles of confrontation. This narrative suggests that the two parties should learn to adjust to working with one another under the pressure of new conditions of adversarial nature.

Certainly, all of the narratives have their own merits. But the reference to the Cold War era comes in handy regardless of which narrative one chooses to share. For the majority of the Russian political establishment, thinking in Cold War terms props up the idea of Russia’s greatness. Perhaps this is one reason why out of all the episodes of the Cold War times, Russia often chooses to focus on détente, the period when – in the face of nuclear disaster – great powers abided by the same rules. This is the period when Moscow felt most equal to Washington.

For the American elites, the Cold War paradigm likewise seems comfortable and understandable. This was an era of rapid American development, an era that helped mobilize the population against a serious enemy, and an era from which America emerged as a winner. Whereas Russians stress détente, Americans, perhaps not coincidentally, frequently highlight the Ronald Reagan presidency (1981-1989) – the period when the US dealt the most decisive blow to the Soviets.

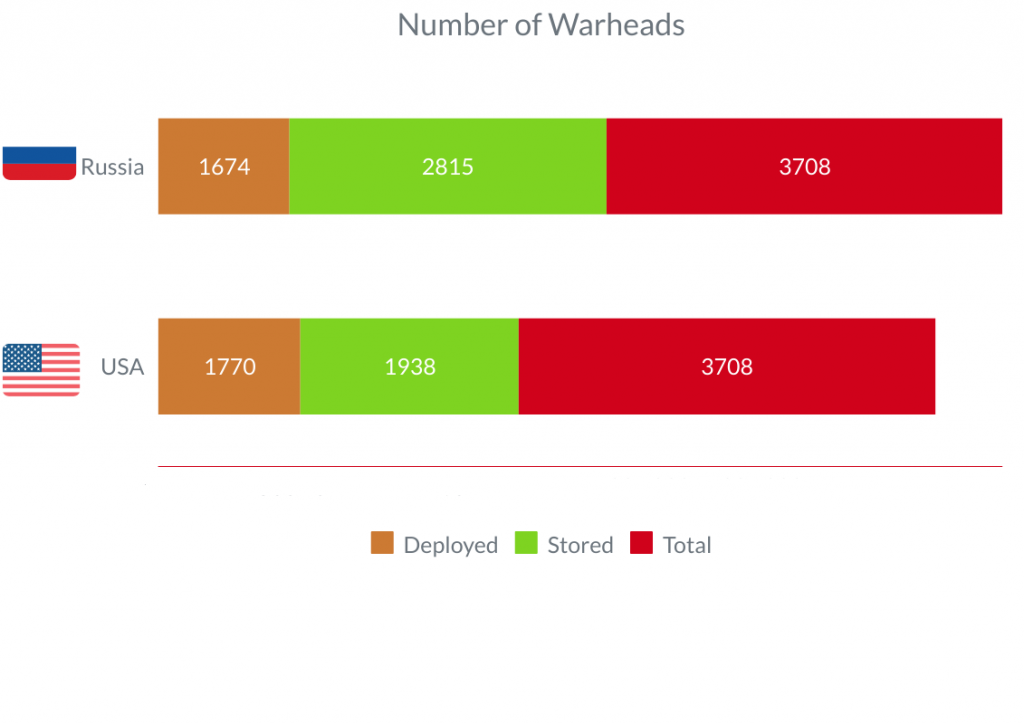

Now that the grand showdown with China is on the agenda, the US decision-makers also evoke the era of the Harry Truman presidency (1945-1953). America needs a new strategy for the containment of China, similar to the one that was designed in the late 1940s and early 1950s to fight the Soviets and communism. There seems to be a bipartisan consensus in Washington that the rivalry with Beijing is systemic and will define the 21st century. Whereas China is a strategic challenger, Russia is a strategic nuisance – and only enjoys the modifier strategic due to its nuclear arsenal, cyber and some space capabilities[4]. This essentially undermines the philosophy that shaped the relationship in the previous era – the systemic struggle of the two mutually respected great powers – and puts the US-Russia relationship into some other category.

“The Russian Federation is interested in maintaining strategic parity, peaceful coexistence with the United States, and the establishment of a balance of interests between Russia and the United States, taking into account their status as major nuclear powers and special responsibility for strategic stability and international security in general. The prospects of forming such a model of US-Russian relations depend on the extent to which the United States is ready to abandon its policy of power-domination and revise its anti-Russian course in favor of interaction with Russia on the basis of the principles of sovereign equality, mutual benefit, and respect for each other’s interests”.

2023 Russian Foreign Policy Concept

Source: Russian Foreign Ministry

(https://mid.ru/en/foreign_policy/fundamental_documents/1860586/)

“The United States, under successive administrations, made considerable efforts at multiple points to reach out to Russia to limit our rivalry and identify pragmatic areas of cooperation. President Putin spurned these efforts and it is now clear he will not change. Russia now poses an immediate and persistent threat to international peace and stability. This is not about a struggle between the West and Russia. It is about the fundamental principles of the UN Charter, which Russia is a party to, particularly respect for sovereignty, territorial integrity, and the prohibition against acquiring territory through war”.

2022 US National Security Strategy

Source: White House

(https://www.whitehouse.gov/wp-content/uploads/2022/10/Biden-Harris-Administrations-National-Security-Strategy-10.2022.pdf)

The problem of mutual perception

The issue of how Russia and the United States perceive one another is important in the sense that it helps to understand a number of critical issues at the center of the expert debate, among others, those concerning the root causes of the confrontation and how far the two parties can go[5]. There is no unanimity on what should be considered as the starting point of the confrontation. Yet, many Russian and American policy analysts share the view that the crisis in Ukraine was not the very cause but rather a concentrated expression of hibernating disagreements between Moscow and Washington. Metaphorically speaking, it was the spark that set on fire the haystack of mutual suspicions and misunderstandings that have been piling up for years. There are arguably four mutual perception images of Russia and the US that dominate the expert and policy discourse at the moment.

1. Both parties strongly believe that the other party started it first. Practically every single issue that Russia and the United States have clashed over in recent few years is deemed to be initiated by the other party. From Georgia to Syria to the Snowden case and to the Maidan protests and the subsequent war in Ukraine, Russia and the US have promoted conflicting narratives and acted out of the assurance that they were on the right side of history while the opponent was not. Such perceptions leave narrow odds of marrying the interests since both are positive of their self-righteousness and expect the opposite party to concede first, if not change its policy course. As a result, mutual grievances keep mounting which is gradually clogging the very communication with each other. Eventually, the parties end up thinking that any dialogue is meaningless.

2. Both countries see one another as declining powers. In the US, policy-making circles would usually point to some statistical evidence in this argument: the state of affairs in the Russian economy and national demographics, ethnic and social issues that make the power vertical rather fragile – all of that topped off with the external challenges that demand a high level of national unity and elite mobilization. None of that, according to the majority of American Russologists and decision-makers, is in place.

The sentiments prevailing in Moscow, in turn, are somewhat similar. Few believe that America is the shining city on a hill, the way they did at the dawn of the collapse of the Soviet Union and onwards. Three decades after the end of the Cold War have exposed America’s thirst for hegemonic world order. Forever wars have shattered its international image and leadership. No matter whether this is a genuine belief or wishful thinking, the perception of America as a colossus with feet of clay is gaining momentum and is getting stuck in the minds of the Russian public and elites. Eventually, this common perception creates an impression in both Moscow and Washington that the power of the opponent has many limits and thus can and should be challenged.

3. Both powers see each other as revisionist. Should the US-Russia relationship be seen through the lens of political psychology, one might see it as a case for what is called fundamental attribution error[6]. The theory suggests that people frequently tend to perceive aggressive behavior as caused by aggressive personality characteristics, whereas aggressive behavior can also often be provoked by situational circumstances. That is to say, the parties tend to overemphasize one’s own policy (even personal) characteristics and ignore situational factors in judging the behavior of the other[7].

In the case of the US-Russian relations, the phenomenon of fundamental attribution error is frequently materialized in the form when one party tends to excuse its own behavior in terms of external circumstances – democracy is under attack, they lied to us about NATO non-expansion[8] – while explaining the behavior of the other party in terms of attributed innate bad qualities – the United States is an imperial power that seeks hegemony, Russia is autocratic, etc[9]. This interpretation is frequently projected onto the regional policies of Russia and the US, and especially true for the post-Soviet space. For example, Russia is frequently castigated for what is seen as its ultimate intolerance of democratic processes in the neighboring countries which is attributed to fundamental vulnerability of the nature of the Russian regime to democratic developments[10]. In turn, Russia’s political establishment often sees the drivers of America’s own foreign policy as sinister in character and strategic in nature thus dismissing any thought that a policy may be a byproduct of an opportunistic move.

Therefore, the phenomenon of the fundamental attribution error largely creates the perception asymmetries in the US-Russian relations and often leads the two countries to erroneous conclusions about one another that subsequently lead to confrontational policies even when you do not have to move there.

4. Both see each other as a source of global insecurity. This perception manifests itself in what the leadership in Moscow and Washington say about the implications of American and Russian policies respectively. Under President Barack Obama (2009-2017), Russia was put alongside the Islamic State of Iraq and Syria (ISIS)[11] on the list of the world’s daunting challenges. President Joe Biden (2021-present) has recently established a direct link between Russia and Hamas[12].

Although President Putin is usually more cautious about calling names, he also does not mince words to say that the world has had it enough with American dominance and policing. Such a vision implies greater focus on one another as the part – if not the reason – of the problem, not the partner to its solution. However, it frequently ignores the other – at times more critical – factors that complicate these problems and clouds any cooperation prospects to tackle more serious challenges and even rules out the possibility of holding the very discussion that seeks cooperation.

Russia and the United States until 2025: no further harm

On top of the destruction of the relationship philosophy of the past and the perception issue of the present, there is a visible exhaustion of the agenda of the bilateral relationship that also casts a shadow on its future. The current state of relations between the US and Russia is largely a result of where things have been drifting since the reset policy of 2010-2011. The policy initially sought to leave Russian-American aspirations and interests in the post-Soviet space outside the equation. To some extent, the tacit agreement to do so was purposeful – otherwise any fresh start in the US-Russia relationship would have been hard to elaborate.

Besides, both nations took some time to recalibrate their respective policies in the region. The war in Georgia in 2008 brought to an end a number of integration projects in the former Soviet Union. The 2008 Global Financial Crisis also hit Russia badly, and it was time for Moscow to gather stones: the then president Dmitry Medvedev was focused on the mega-idea of modernization. For the Obama administration, the post-Soviet space did not rank high on the foreign policy priorities list – it sought to clean the mess left by the George W. Bush administration (2001-2009) in Afghanistan and the Middle East and was gradually pivoting to the East. In practice it meant redistribution of political, military, and financial resources elsewhere.

The apparently good personal chemistry between Medvedev and Obama gave the initiative to the much desired at the time political will. Cardinal Richelieu’s behest to start any negotiations with the easiest matters was at play. Certainly, the Iranian nuclear issue, the New START Treaty and the deals over Afghanistan were far from being easy. But they were the areas where both Russia and the US had a solid mutual interest in seeing each other as partners. Yet, once this agenda had exhausted itself and the old-new bilateral grievances would prop up here and there – from the Arab Spring, Snowden case to Syria – the cooperative spirit evaporated rather swiftly.

No matter whether the return of Vladimir Putin to the Kremlin was the root cause that only snowballed the confrontation – as Americans would claim – or it simply added a bit of spice to systemic problems, the post-Soviet issues would have been eventually put on the agenda sooner or later. Piling disagreements between Moscow and Washington long before the political crisis in Ukraine in the late 2013-early 2014 brought the unsettled post-Soviet affairs into the spotlight. The crisis in Ukraine switched the rivalry from the competition to the confrontation mode. The reset that was once deemed to give the relationship a fresh start, eventually put it on a downward trajectory.

Rare episodes of bilateral cooperation that would happen ever since – such as the joint Putin-Obama initiative for the destruction of Syria’s chemical arsenal in 2013 – have not developed into something sustainable and long-term. Russia castigated the US for its superpower arrogance, which is believed to have prevented Washington from seriously considering Russian proposals to address the issues of mutual concern[13]. The West, in turn, labeled Russian behavior in international conflicts (particularly in Ukraine and Syria) as the revisionism of a declining power[14].

The election of Donald Trump to the office in 2016 and the widening socio-political divide in the US made Russia a toxic factor in American domestic politics – an unpleasant makeweight to its usual status of a foreign adversary. The relations between the two nuclear superpowers narrowed down to the topic of the interference of these powers in each other’s domestic affairs. The word cooperation gradually disappeared from bilateral parlance, giving way to de-conflicting when American and Russian troops came dangerously close to each other in Syria.

The list of issues that the states were ready to discuss had been dramatically reduced. The fallout from the Trump-Putin summit in Helsinki on July 16, 2018, made it crystal clear that even the discussions of important state affairs were fraught with further complications and even sanctions. The format of presidential summits therefore lost its significance and was no longer needed as an instrument of crisis diplomacy. What followed was only logical continuation of the general negative trend: the communication channels were cut off; diplomatic missions were shut down. The only intriguing question that remained was which new crisis or scandal would plunge the relations to new lows.

From Moscow’s perspective, the Democrats sought to punish Russia for its interference into the presidential elections in the US and the alleged support for Trump. The Republicans, for their part, appeared keen to rid themselves of their newfound status as the pro-Russia party – the status largely driven by Trump’s complimentary remarks about Vladimir Putin and the general appreciation expressed by Trump’s conservative base for Putin’s style of governance – and therefore aimed to punish Russia in order not to appear weaker than their Democratic opponents. At the same time, the United States expressed confidence that as soon as America needed Russia’s assistance on major issues, Moscow would be happy to help. This attitude apparently persists: “You can walk and chew gum at the same time”, – as President Joe Biden would put it[15].

Russia found this approach disappointing. Moscow eventually recalled its Ambassador Anatoly Antonov from Washington after Biden had agreed in his interview with the journalist George Stephanopoulos, that Putin was a killer[16]. The move may have been largely symbolic – after all, Ambassador Antonov returned to Washington shortly – but it essentially exposed the need for a reassessment of Russia’s relations with the United States. The framework designed in the post-bipolar world with the elements of the Cold War era that kept the relations symbolically afloat in the 1990s has faded into oblivion after Putin’s Munich speech in 2007. The paradigm of the 2000s lost its value with the Crimea’s reunification with the Russia in the spring 2014. The killer moment represented the cut-off point.

In an effort to halt the escalation of tensions, presidents Joe Biden and Vladimir Putin decided to give the summit diplomacy yet another chance. Following the presidential meeting in Geneva on June 16, 2021, Moscow and Washington established two channels: a diplomatic channel led by the then US Deputy Secretary of State Wendy Sherman and Russian Deputy Foreign Minister Sergey Ryabkov that sought to discuss arms control and cybersecurity; and the military channel spearheaded by respective Chiefs-of-Staff, General Mark Milley and General Valery Gerasimov.

The agenda fatigue

The channels established at that time served as a part of political infrastructure to manage confrontation and were instrumental in at least two ways. First, they helped address immediate security challenges, such as avoiding a direct military clash in theaters where Russian and the US forces operate in close proximity to one another or take actions that the other party may consider provocative. Second, they served as a long-term objective of maintaining strategic stability in the new technological era. The nature of strategic stability, however, has recently been changing both quantitatively and qualitatively. With regard to the former, China has been catching up with Russia and the US in building up its nuclear capabilities, including missiles and the means of their delivery. As for the latter, the development of precision-guided and hypersonic weapons that are almost as destructive as their nuclear counterparts but are not subject to the same treaty regulations is a serious concern to all global security stakeholders. The rise of technology runs a risk of shifting the focus of strategic stability from nuclear arms to the cyber domain altogether: like nuclear weapons, cyber warfare has the potential to be the marker of a military might and a great power status.

No one in Moscow or Washington questioned the strategic importance of the issues. Yet, the negotiation infrastructure designed to work on these issues was – and remains – ultimately defense-oriented which means that it makes the parties find ways to fend off (mostly military) threats but it is not designed to promote cooperationin other areas. The fact that the channels failed at clamping the break-out of large-scale military hostilities in Ukraine in February 2022 is a grim testament to it.

The truth of the matter that the US-Russian relationship is in dire need of a comprehensive common agenda was glaringly apparent every time Russians and Americans got together – in academia, expert circles, or as diplomatic working groups. This was the case even before the launch of Russia’s Special Military Operation in Ukraine. The parties would tend to energetically seek a positive agenda, even as the energy of the US-Russia relationship was gradually waning.

The agenda that could at least have got the parties to consider cooperation a decade ago – for instance, the cooperation on Afghanistan or counterterrorism – was no longer interesting for Moscow and even less exciting for Washington. Climate change is now a high-priority issue for the US and is often brought up in conversations on the future of the US-Russian relationship, but there is little here for Russia and the US to talk about. Russia’s reliance on oil and gas as its primary energy resources, the very structure of its economy, its small domestic market, its climatic conditions, and its vast geography do not militate against the rapid development of a green economy, especially now that the European market is hard to get to and Moscow has to look for new markets for the commodities export. It does not help that many senior members of the Russian government take it for granted that the climate change agenda has been pioneered by the West as a tool for maintaining its economic, technological, and political dominance and is nothing more than an upgraded way of the West to continue colonizing less developed nations through the norms-setting policy in key areas that are important to the very survival of nations. In the light of all of that, it is actually a good thing that Russia has not yet taken a serious interest in the climate change agenda, as it is likely to diverge from the American agenda and propose its own vision for how things should work in this area.

Conclusion

The post-Cold War era is over. The world faces yet another historic inflection point. US-Russia relations are no longer central to global international relations, but when it comes to global security there is barely more important bilateral relationship in the world. The previous paradigm for the relationship has been exhausted, yet no new paradigm has yet emerged as of now. It may take some time – and a few election cycles in the US and a change of power in the Kremlin – to create a situation that is qualitatively different from what we are observing today.

Today, both the US and Russia are, for their own reasons, looking inward. The state of relations between Russia and the United States is now less determined by bilateral dynamics and more by domestic considerations and the overall outside dynamics – be these the crisis over Ukraine, the developments in the post-Soviet space, the Middle East or Asia-Pacific. This is the new normal in the relationship. No matter how serious or successful Russia’s Pivot to the East is, it is neither the replacement nor escape from Russia’s own strategy towards the West. If the systemic problems that continue to plague US-Russia relations are still in place, it will echo in the Asia-Pacific where Moscow and Washington may very soon discover that they have diverging interests as well.

Under the unpredictable circumstances, the best solution for the present moment would, perhaps, be taking a strategic pause in order to critically assess the importance of relations for each country. Russia should ask itself what exactly it wants from the United States in the new era. The US, in turn, should ask itself whether its current approach to Russia is in America’s long-term interests.

Five years hence, we may well see a picture similar to what we are observing today: Russia and the US on opposite ends of almost every regional conflict; persistent divisions in some of the post-Soviet states; economic crises that have not brought the parties together. Looking at the relationship in a ten-year perspective, there is a chance that relations will have a more optimistic outlook. In fact, both countries face three of the same major challenges that may define them in the 21st century: how smoothly they navigate periods of elite change; what type of social contract and control system their governments establish with the so-called Big Tech; and their respective relationships with other influential regional powers (India, the EU, Türkiye, Iran, etc.). Russia and the US may still hold divergent values, but they may also emerge as the two big powers that understand each other’s red lines and do not interfere in each other’s internal affairs. If not, a decade from now, commentators will still be referring to the level of the US-Russian relations as being the lowest since the end of the Cold War.

[1] Legvold R. Managing the New Cold War // Foreign Affairs, July-August, 2014. URL: http://harriman.columbia.edu/files/harriman/content/Managing%20the%20New%20Cold%20War.pdf; Monaghan A.A. “New Cold War”? Abusing History, Misunderstanding Russia // Chatham House, May, 2015.URL: https://www.chathamhouse.org/sites/files/chathamhouse/field/field_document/20150522ColdWarRussiaMonaghan.pdf. Chatham House is included in the List of foreign and international nongovernmental organizations whose activities are recognized as undesirable on the territory of the Russian Federation. – Editor’s Note.

[2] Kalb M. Imperial Gamble: Putin, Ukraine, and the New Cold War // Brookings, 2015.

URL: http://www.brookings.edu/events/2015/10/26-russia-ukraine-imperial-gamble.

[3] Applebaum A. The Russian Empire Must Die // The Atlantic, November 14, 2023. URL: https://www.theatlantic.com/magazine/archive/2022/12/putin-russia-must-lose-ukraine-war-imperial-future/671891/.

[4] Kendall-Taylor A., Shullman D.O. China and Russia’s Dangerous Convergence: How to Counter an Emerging Partnership // Foreign Affairs, May 3, 2021. URL: https://www.foreignaffairs.com/articles/china/2021-05-03/china-and-russias-dangerous-convergence.

[5] See: Suchkov M. Whose Hybrid Warfare? How “the Hybrid Warfare” Concept Shapes Russian Discourse, Military, and Political Practice” // Small Wars and Insurgencies, 2021. Vol. 32(3). Pp. 415-440.

[6] See: Markedonov S.M., Suchkov M.A. Russia and the United States in the Caucasus: Cooperation and Competition // Caucasus Survey, 2020. URL: https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.1080/23761199.2020.1732101.

[7] Ross L. The Intuitive Psychologist and His Shortcomings: Distortions in the Attribution Process / Ed. by L. Berkowitz // Advances in Experimental Social Psychology, 1977. Vol. 10, Pp.173-220. New York: Academic Press. URL: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S0065260108603573#preview-section-abstract.

[8] Sushentsov A., Wohlforth W. The Tragedy of US-Russian Relations: NATO Centrality and the Revisionists’ Spiral // International Politics, 2020. Vol. 57 (3). Pp. 427-450.

[9] Sushentsov A. 2018. Psychological Underpinnings of Russia-US Crisis: Symmetrical Paranoia // Valdai Discussion Club, September 4, 2019. URL.: https://valdaiclub.com/a/highlights/psychological-underpinnings-of-russia-us-crisis-sy/.

[10] Rojanski M. Understanding the US-Russia Relationship // The Wilson Center Podcast “Need to Know”, 2019. URL: https://soundcloud.com/the-wilson-center/need-to-know-episode-1-understanding-the-usrussia-relationship-matt-rojansky?in=the-wilson-center/sets/need-to-know.

[11] The organization is recognized as terrorist in the Russian Federation. – Editor’s Note.

[12] Smith D. Biden Draws Direct Link between Putin and Hamas as He Urges Aid for Israel and Ukraine // The Guardian, October 20, 2023. URL: https://www.theguardian.com/us-news/2023/oct/20/joe-biden-tv-address-to-nation-oval-office-speech-vladimir-putin-hamas-aid-for-israel-ukraine

[13] Speech and the Following Discussion at the Munich Conference on Security Policy // Official Website of the Russian President, February 10, 2007. URL: http://en.kremlin.ru/events/president/transcripts/24034.

[14] Pisciotta B. Russian Revisionism in the Putin Era: an Overview of Post-Communist Military Interventions in Georgia, Ukraine, and Syria // Italian Political Science Review, 2020. № 50. Pp. 87-106.

[15] Dobbins J. In Its Relations with Russia, Can the US Walk and Chew Gum at the Same Time? // US News & World Report, August 6, 2017. URL: https://www.rand.org/blog/2017/08/in-its-relations-with-russia-can-the-us-walk-and-chew.html.

[16] Troianovski A. Russia Erupts in Fury Over Biden’s Calling Putin a Killer // The New York Times, March 18, 2021. URL: https://www.nytimes.com/2021/03/18/world/europe/russia-biden-putin-killer.html.

E16/MIN – 24/04/15