The proverbial “interesting times” are again upon us. Unlike at the turn of the 1990s, when the change of world order per se was essentially peaceful and consensual, this time rivalry among great powers is visible, and occasionally violent. Realpolitik is back, with a vengeance. The post-Cold War global hegemon, the United States of America, is fighting back to preserve its primacy, very much against the odds. China, longtime an economic colossus keeping a reasonably low geopolitical profile, is rising fast as a technological and military power, with a growing diplomatic clout. India, resentful over Western colonial domination that for two centuries held it back economically and technologically, is determined to repeat China’s success, although in its own inimitably Indian way. Russia, having made a comeback from its catastrophic downfall as the Soviet Union, has ended its futile quest for an autonomous position within the wider West, and is charting its own way as a distinct “civilization state”.

Currently, these are the four truly sovereign major players in the world system whose policies will largely shape the new international order to replace the post-Cold War American dominance and the 500-years-old supremacy of the West.

The Leading Powers

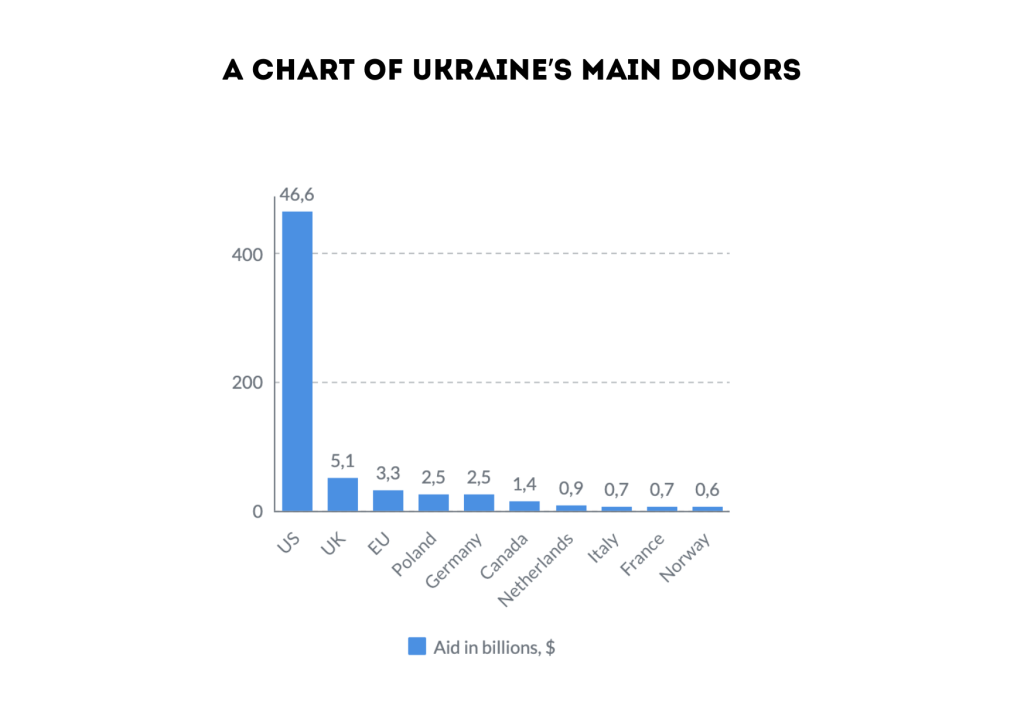

The dynamics in the relations among these four players are high. Russiahas been defending its vital national security interests against the collective West of NATO/EU countries in a proxy war in Ukraine. The conflict there, which began in 2014 with the Western-engineered coup d’etat and Russia’s reaction to it in Crimea and Donbass, escalated in 2022 to a full-scale war between Russia and the Western-backed/-trained/-equipped Ukrainian forces along a 2,000-km-long frontline. Early in the war, the Joe Biden Administration in Washington set the goal of inflicting a strategic defeat on Russia[1] – something that American leaders carefully avoided during the Cold War. The Ukraine conflict then intensified and threatened to lead to a direct clash between Russia and NATO countries, raising the specter of a nuclear conflagration engulfing not just Europe, but much of the world.

Reacting to the challenge of China’s economic and technological ascendance, the first Trump Administration in the United States dumped America’s long-lasting “hedge and engage” mode of its China strategy and opened a trade and technology war against Beijing. This course was inherited and embraced by the Biden White House. Against this background, Sino-U.S. geostrategic tensions over Taiwan and the South China Sea have heightened. An arms race between the world’s two biggest economies has quickened its pace. Donald Trump’s second coming to the U.S. presidency resulted in an even bigger emphasis in Washington’s foreign policy on thwarting China’s challenge to American global dominance.

Washington’s attempt to simultaneously hold back China and Russia has naturally provided an additional impetus for the Sino-Russian strategic partnership. The partnership itself, which began as far back as 1989 with the reconciliation between Moscow and Beijing, is largely driven by the two countries’ national interests and is not a latter-day version of the Sino-Soviet bloc of the 1950s. However, faced with American pressure, Russia and China have upgraded their cooperation and coordination, including in the politico-military field. In contrast to the 1970s, when the Nixon Administration, by means of the much-celebrated Triangle strategy, successfully managed to play Beijing off Moscow, or to the 1990s, when both Russia and China prioritized cooperation with Washington, the United States has now succeeded in turning two of Eurasia’s principal powers into its adversaries: a major strategic blunder of American foreign policy.

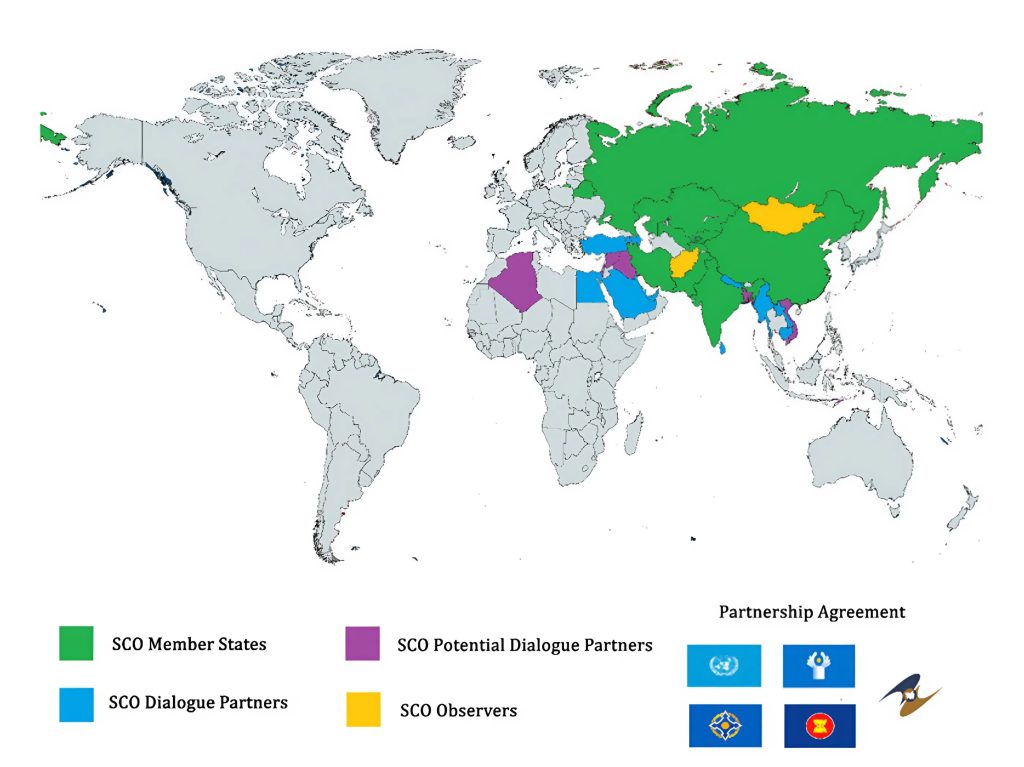

Meanwhile, Eurasia’s third major power, India, has been raising its international profile as a newly non-aligned power. India is on good terms with the United States, whom it sees as a vital partner in technology and a key market. New Delhi also entertains a close relationship with Russia, that has been India’s premier source of defense equipment and a highly reliable political partner. India is wary of China due to historical disputes over the border in the Himalayas, Beijing’s support for Pakistan, and more generally as an economic and geopolitical rival in Asia. In May 2025, India has had to fight a brief (87-hour) war against Pakistan, provoked by a gruesome terrorist attack against civilians in Kashmir. New Delhi’s careful balancing game is illustrated by its simultaneous membership – alongside Russia and China – in the BRICS group and the Shanghai Cooperation Organization (SCO), and in the QUAD format with the United States and its allies Japan and Australia.

Other Important Players

The four leading powers at the start of the second quarter of the 21st century are not the only significant players on the world stage, of course. The countries of Europe – the EU member states and the United Kingdom – are desperately trying to regain their international relevance in the face of the challenge posed by the Ukraine war and the policies of the Trump Administration. Essentially, Donald Trump has reversed the state of play within the Western world. He drastically reduced Washington’s historical commitment to support and indulge U.S. allies and clients around the world. The focus of Trump’s White House has shifted from ensuring that the periphery of the American empire can thrive and expand (enabling “the march of democracy without borders”) to shoring up the empire’s somewhat hollowed-out imperial homeland (“making America great again”). Thus, Trump openly treated the Europeans, alongside Japan, Canada, Australia and others as simultaneously political vassals and economic competitors. The 47th U.S. president is capitalizing on American security commitments, which are no longer taken for granted. One can argue that Trump’s putting price tag on U.S. support and raising tariffs at the same time is his pre-emptive strike at multipolarity. It is meant to ensure that, in a multipolar world, which is coming anyway, America is the biggest and the strongest pole of all, able to enjoy primacy with reduced responsibility.

Unable and unwilling to stand up to the United States, but adamant to remain in the game, the Europeans have used the Ukraine conflict to solidify their union by treating Russia as if it were a mortal danger to themselves. Within a few years starting from the mid-2010s, they have succeeded in re-identifying the core purpose of the EU as an anti-Russian bloc. This is a third iteration of the prime objective of European integration, since preventing another war among the European powers (after 1945); and making Europe “whole and free” by means of incorporating the Eastern European countries – all the way to the Russian border (after 1989). This explains the massive European political, financial and military investment in Ukraine, and the deep involvement of the European countries, particularly of Britain, France, and Germany, in training, equipping, advising, and guiding Kiev’s war efforts against Russia, complete with their suspected involvement in the acts of sabotage and even terrorism inside Russia.

These activities have made Moscow fundamentally reconsider its assessment of Europe. No longer Russia’s preferred foreign partner as in the post-Cold War times, or even a seemingly reluctant follower of Washington’s policies, as during the Cold War, Europe, in many Russian eyes, has re-emerged as a coalition of historical enemies driven by a desire to defeat and if possible, destroy Russia[2]. Today’s Europe, from that perspective, has much in common with the Europe under Napoleon that invaded Russia in 1812, or under Hitler in 1941. Both those invasions assembled combined forces of many countries which were allied or subservient, respectively, to Paris and Berlin. The difference is that the united political Europe of the 2020s, while it has as much hatred, fear and contempt for Russia, has far less power than its historical predecessors. Yet, the degradation of Europe’s strategic thinking as well as its absence, since the 1950s, from strategic decision-making, even about itself, raise concerns in Russia about the potential for European countries’ fateful miscalculation.

What is particularly stunning is the change in Russian attitudes toward Germany. Russians forgave Germany for the horrendous civilian casualties (over 15 million out of 27 million people) resulting from Hitler’s invasion. They gave their consent for the two German states’ unification and withdrew their troops from East Germany. They subsequently even thought that Germany was their country’s best friend in Europe, and approached it accordingly. Now, Russians are stunned to see Berlin as the frontrunner among the supporters of the Kiev regime – a regime whose ideological roots go all the way to erstwhile Nazi collaborators in western Ukraine who are elevated now to the position of father figures of the present-day Ukrainian state. Besides supporting Kiev, Berlin aims at massively expanding Germany’s defense industry and turn the country into the main pillar of Europe’s military might. Germany’s and Europe’s rearmament and remilitarization plans are being laid out explicitly with the objective of being able to fight Russia already in the medium term. Fifty years after the signing of the Helsinki Final Act of the Conference on Security and Cooperation in Europe which stabilized the Cold War’s bipolar order, and 35 years after the Charter of Paris for a New Europe, which appeared to offer a prospect for cooperation and integration across the now defunct Iron Curtain, NATO and Russia are closer to a shooting war between themselves than they have been at any time since the 1962 Cuban missile crisis.

East Asia and Eastern Europe are not the only battlefields in the new confrontation. In the Middle East, the decades-old Israeli-Arab/Palestinian conflict has been replaced by one between the leading regional powers, Israel and Iran. The Israeli leadership, with full backing of the United States, has used the 2023 mega-terrorist attack by HAMAS to try to deal a crushing blow to its main regional rival, Iran, which is a member of the China- and Russia-led Shanghai Cooperation Organization (SCO) and the BRICS group. In June 2025 Israel and the United States attacked Iran’s nuclear facilities to annihilate the program. Iran hit back at Israel with its own missiles. As a result, Tehran’s nuclear program has suffered a setback, but it has not been bombed out of existence. New clashes between Israel/U.S. and Iran are thus likely – unless Iran bows to the pressure and changes course, which cannot come without a major domestic clash of interests.

The fact that in the shooting wars between the nuclear powers: Russia, on the one hand, and America, Britain, France, on the other, in Ukraine; between India and Pakistan in South Asia; and between Israel and the United States against near-nuclear Iran in the Middle East, nuclear weapons have not been used, so far, should not breed illusions: for the major powers of the world, war has re-emerged as a usable tool not only in the peripheral engagements (as in, e.g., Afghanistan), but in direct major-power conflicts – by proxy or not.

Russian Transformation

Against this background, the trends in Russia’s situation noted in the previous edition of the Security Index have grown stronger. Above all, the country’s domestic transformation, while difficult, is deepening. The notion of Russia as a unique civilization state first enshrined in the 2023 Foreign Policy Concept[3] is being more widely accepted. The country’s political system – with its clear emphasis on the central role of the State and the importance of the unity of leadership – is being less and less linked to the Western concept of liberal democracy. Instead, it is being increasingly legitimized by Russia’s own historical experience and the practical needs to withstand the pressures from the West and the complexities of the ongoing war environment. A new set of values is emerging – away from the post-Soviet dominance of money and material benefits, and closer to the traditional Russian emphasis on patriotism, family and things spiritual. Some sort of a cultural revolution is quietly taking place, though its victory is still far from assured.

Russia’s war effort is being supported by its defense industry which has been able to dramatically increase production of weapons and materiels. Russia is in fact competing against the combined capacities of Ukraine’s Western backers. While the economy at large has not been completely mobilized for war, an industrial policy has begun to emerge, with the state becoming much more active in directing economic development than at any time since the end of the Soviet period. Despite the 30,000-plus Western sanctions and other restrictions imposed on Russia over the past decade, but particularly since 2022, and the inevitable hardships of the war, including its substantial human losses, patriotism is running high[4], with the support for the Kremlin policies, including the conduct of the war, remaining steady at a record-high (around 80%) level.

One major change in Russia’s international environment has been Europe emerging as the principal foreign adversary, and even an enemy of Russia, replacing the United States in that position. Britain, France and above all Germany are now widely considered Russia’s principal foes, a throwback to the 19th and early 20th centuries. In Germany’s case, a parallel with the 1941 Hitler invasion of the Soviet Union is all too obvious. This is a reaction in Moscow and across Russia to the Europeans’ coming to the fore of the Western effort to support Kiev politically, financially and militarily – following Trump’s desire to stop the fighting or at least distance himself from what he calls “Biden’s war”. The result is that Europe, which after the end of the Cold War was considered the world’s model region in terms of demilitarization, reconciliation and cooperation, isbecoming one of the main hotbeds of tension and a likely battlefield, even after the end of the shooting war in Ukraine.

Toward the United States, the attitudes in Russia have become more nuanced with the advent of the Trump Administration. America remains Russia’s most formidable adversary; however, there is a hope that some sort of an understanding could be reached with Washington which at least would lead to Trump winding down its participation in the Ukraine war. Should that happen, there is a potential for a modicum of U.S.-Russian cooperation elsewhere, in particular in the economic field. This hope, which resulted from the August 2025 Alaska meeting between Presidents Putin and Trump, is tempered, however, by the existence of the dominant anti-Russian majority within the U.S. political class, with the neocons on both sides of the aisle still in positions of power and influence. Reversing that course and adopting a realist and pragmatic attitude toward Russia would require nothing less than a revolution in U.S. foreign policy. As Trump’s attempts at brokering peace in Ukraine have demonstrated, a coalition of American Democrats; the neocons from both parties; and U.S. European allies can massively weigh in on Trump’s policies.

Russian Priorities

Russian foreign policy priorities have basically remained unchanged since 2022. If anything, they have become more pronounced and better established. Top among them is strengthening the country’s real sovereignty. This means enhancing Russia’s economic resilience in the face of sanctions and restrictions; expanding the country’s technological capabilities and reducing its dependence on others; acquiring intellectual sovereignty complete with the philosophical underpinnings of a unique worldview and some sort of a practical ideology that would guide the state and provide a clear orientation for the bulk of the Russian people. Four years into the war, all of this, of course, is still more of a plan than actual reality.

Moscow’s short-term – up to three years – priorities are focused on achieving an acceptable outcome in Ukraine. This means a stable political settlement, not a truce. In security terms, this would mean transforming Ukraine into a neutral buffer state between Russia and the NATO/EU Europe. In future, Ukraine should be forever barred from joining NATO; host no foreign forces in its territory, whether on a permanent (bases) or a temporary basis (exercises, training missions, and the like); accept limits on its military power and defense industry. More broadly, Russia seeks a politico-military equilibrium on the dividing line between itself and NATO, making the situation on its western flank essentially predictable, but much of this is for the medium- and longer-term future.

In territorial terms, an acceptable settlement would mean securing the entire territories of the four regions – two in Donbass (Donetsk and Lugansk) and two in Novorossia (Zaporozhie and Kherson) which joined Russia in the fall of 2022 and are now part of the Russian Federation’s constitutional space. Moscow is determined to assume full control all of those territories, about a third of which is still in Kiev’s hands. To achieve this, Moscow is prepared to trade some small pieces of land in Kharkov, Sumy and other Ukrainian oblasts that Russian forces hold. Russia would also insist on the international recognition of the its borders, including, besides Donbass and Novorossiya, also Crimea and Sevastopol, which acceded to Russia in 2014.

In political terms, Russia wants a neutralist regime in Ukraine to replace the one which it sees as having Banderist (i.e., pro-Nazi) roots, and which espouses ultra-nationalist and Russophobic ideology, and practices terror. In a crude comparison, Moscow would probably settle for a regime that is reminiscent of the one established in Finland, a Hitler ally, which it defeated in 1944. This means a predictable government, broadly loyal to Russia in foreign and security policy terms, and widely autonomous in handling domestic affairs. Such a regime would need to rediscover Ukraine’s bilingual (Ukrainian/Russian) character, restore the position of the Russian language and culture alongside the Ukrainian language and heritage, and honor the rights of the Ukrainian Orthodox Church that is affiliated with the Moscow Patriarchate.

To help achieve these objectives, Russia’s foreign policy strategy would need to cement Moscow’s relations with Minsk. In the course of the Special Military Operation in Ukraine, Belarushas emerged as Russia’s only true ally among the former Soviet republics. The Union State of Russia and Belarus has recently acquired a nuclear dimension. Moscow’s new nuclear doctrine has explicitly extended a nuclear umbrella to Belarus. For the first time since the dissolution of the Soviet Union, Russia has deployed its non-strategic nuclear weapons in the neighbouring country. Medium-range nuclear-capable missiles, such as the Oreshnik, are also on its way for deployment there. Belarusian leader Alexander Lukashenko, in power since 1994, won another five-year term in 2025. It is in the Russian interest that power transition in Belarus, whenever it happens, results in an even closer relationship between the two countries.

Moscow’s other overt wartime ally has been the Democratic People’s Republic of Korea (DPRK). A friend in need is a friend indeed: Moscow’s ties with Pyongyang have been strengthening rapidly. The Korean People’s Army (KPA) 11,000-strong deployment to the Kursk region in 2024-2025 was instrumental in liberating part of the region from the Ukrainian forces. As long as the war continues, Russia would materially benefit from a fresh deployment of the KPA troops to the Russo-Ukrainian border that would relieve Russia’s own forces to fight inside Ukraine. Continued provision to Russia of North Korean artillery ammunition and other materiel constitutes important assistance to Russia’s war effort as it faces the Western coalition’s massive support for Kiev. In return, Moscow is providing North Korea with the things that Pyongyang values, from energy to space technology. Based on the 2024 bilateral treaty on strategic partnership which includes a mutual military assistance clause, Russia and North Korea have upgraded their relationship to a functioning alliance.

Expanding and deepening ties with non-Western countries – often referred to now as the Global Majority – is Moscow’s top diplomatic priority, particularly in terms of economic security and political dialogue. BRICS members stand out as the most important group in that category. In particular, Russia’s relations with China are of critical importance, given the geopolitical position of both countries vis-à-vis each other, China’s huge industrial capacity, its energy and other raw materials requirements (which Russia can help satisfy), technological prowess, military power and diplomatic clout. Even though Beijing professes neutrality in the Ukraine conflict, and its stake in protecting its access to the Western markets makes it careful while doing business with Russia, China’s de facto backing of Russia (even if it is limited) is of unique importance to Moscow. Making sure that the Russo-Chinese strategic partnership continues to grow strong and develop is a first-order priority to the Kremlin.

India is also Russia’s strategic partner that needs constant attention. Even though Delhi entertains close relations with the United States (institutionally through the QUAD group) and rejects any notion that BRICS is an anti-Western bloc, it has emerged as a major buyer of a discounted Russian oil – and thus an alternative to the European market that has been closing fast to Russia. The rough handling of India by Donald Trump in his tariff wars and his demand that other countries do not buy Russian oil has infuriated many Indians and tempered somewhat the pro-U.S. tilt in Indian society. For Russia, this is a positive development, which strengthens India’s strategic independence. A closer alignment among Eurasia’s three great powers, Russia, India, and China (RIC) has been Moscow’s strategic priority since the mid-1990s.Yet, realizing the potential of such an alignment it would require a fundamental improvement of the Sino-Indian relationship, which is plagued by mutual suspicion and grievances. In August 2025, Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi’s first trip to China in seven years, to attend a SCO summit, inspired some hopes in Moscow.

Relations with other members of the BRICS group, which expanded in 2024, are also prioritized in Moscow’s foreign policy, though in the short term they do not come close in significance to ties with Beijing and Delhi. Moscow’s relative passivity during the 12-day war that Israel and the United States waged in 2025 against Iran revealed the shallowness of the strategic partnership – even now treaty-based – between Moscow and Tehran. The work on the North-South logistical corridor linking Russia to India via Iran, which Russia actively seeks to re-energize, has been marking time, creating little enthusiasm in Iran. Russia has had more interaction with Iran’s Gulf neighbour and fellow BRICS member, the United Arab Emirates, which has turned into a gateway for Russians to the Middle East and beyond. The Shanghai Cooperation Organization (SCO) has not had a particularly good year, with two of its members – India and Pakistan – waging a short war in 2025.

Russia is not limiting its Global Majority priorities to the BRICS and SCO groups, of course. It works not to lose the momentum with the African states; is busy to organize the first Russia-the Arab League summit in the Fall of 2025; builds on the already vibrant ASEAN connection – especially with Vietnam, Indonesia, Malaysia, Myanmar, Laos and Thailand. In 2024, Russia has had to witness the fall of a friendly regime in Damascus, but has been trying to salvage its two bases in Syria, which are important as a way station en route to Africa, the continent that Russia is now rediscovering for economic and other opportunities. Moscow’s decision to recognize the Taliban regime in Afghanistan signals its desire to secure its southern flank. Relations with Turkey, a NATO member with an autonomous regional policy in the Middle East, the South Caucasus and Central Asia, will continue to be a combination of competition and cooperation. It is in Moscow’s interest that the latter prevails over the former.

In Central Asia, Russia’s immediate priorities center on strengthening economic ties with the members of the Eurasian Economic Union – Kazakhstan and Kyrgyzstan, and also with Uzbekistan, the region’s biggest nation. In the South Caucasus, Russia is essentially acting in a holding pattern. It aims at containing the newly surfaced serious tensions with Azerbaijan, managing Armenia as it is drifting away toward the West, and keeping things steady with Georgia as Tbilisi defends its sovereignty now vis-à-vis the EU. At the same time, Moscow has markedly intensified its interaction with Abkhazia, materially integrating it with Russia. In Moldova, a cleft country between the EU and Russia, Moscow supports groups that favor politico-military neutrality and restoring economic links with Russia. As long as the Ukraine war lasts and sucks a lot of energy of Russian foreign policy, the former Soviet countries will probably remain on the backburner of Moscow’s foreign policy.

In the medium-term – from three to five years – Russia would need to manage the continuing confrontation with the West, promoting its interests while avoiding a head-on collision with its adversaries. The end of fighting in Ukraine will not bring peace and reconciliation with Russia’s European neighbours. Moscow’s goal would be to separate, to the extent possible, its relations with the United States from those with the European Union countries. America, with its basic self-confidence and a global agenda, may be more amenable to a more productive relationship with Russia. By contrast Europe, in a sharp contrast to Moscow’s post-1945 worldview of its western neighbours, has emerged as Russia’s main adversary. The current political elites of Europe, as they despair of the decline of their world role, appear weak, hysterical, and blindly Russophobic. In dealing with Europe, Moscow would prioritize deterrence of the anti-Russian forces, led by the United Kingdom, Germany and France, and selective engagement with those countries, like Hungary, Slovakia and potentially others, that are prepared to act in their national self-interest.

Russia’s mid-term strategy would seek to prevent a major war between NATO and Russia, which might be sparked off by renewed tensions in Ukraine; some maladroit moves by the neighbours (such as the Baltic States), or provocations (engineered, e.g., by Britain) going awry. Deterrence based on Moscow’s demonstration of its upgraded arsenal of weapons systems, now including medium-range ones, and its readiness to use them in a crisis situation, would be the chief means of war prevention.

U.S. adversity toward Russia, so deeply entrenched in the American ruling elite, will not disappear soon. Moscow, however, will remain open to contacts with Washington on some issues, from regional affairs – e.g. the Arctic, to economic cooperation – e.g., rare earths. Restoring a meaningful dialogue on strategic stability is another area of potential Russo-American interaction. Yet, the overall importance of relations with the United States in Russia’s foreign policy will be far below the levels of the second half of the 20th and the early 21st centuries.

Should Russia-U.S. dialogue bear fruit or even continue in a sustained mode, this could at least partially unlock the potential of Russian-Japanese and Russian-South Korean economic exchanges. Tokyo and Seoul, which would not break with Washington’s policies on Russia, bear little animus against Moscow – unlike Brussels and the European capitals. America’s Asian allies’ attitude toward relations with Russia could resemble the approach taken by Turkey, a NATO ally with a complex, but working relationship with Russia. If this happens, Moscow would be happy to resume economic cooperation.

Russia’s long-term priorities are centered on the goal of self-empowerment. Having proclaimed itself a civilization state, Russia would need to live up to that notion. The bulk of the tasks it would have to complete before the goal is reached are domestic, from winning economic and technological sovereignty to achieving intellectual independence as a “sovereign humanity” on a par with the Euro-American community, China, India, the Muslim world, and others. In foreign policy terms, Moscow’s priorities are focused on helping create a new non-hegemonic world order – post-American and post-Western.

On the world level, this means creating institutions which would be free from Western domination. BRICS looks like a useful starting platform for this. There are no illusions about the unity of BRICS, which remains highly heterogeneous in a lot of ways, but interaction within BRICS offers precious experience of institution-building without Western guidance. Essentially, the world-level effort focuses on a new financial architecture but covers a wide range of issues, from energy and food security to a dialogue of civilizations as a new way of providing guidance to humanity as a whole.

On the level of Eurasia, the world’s largest continent, the Shanghai Cooperation Organization (SCO), for all its internal divisions, is a platform for managing a security and development agenda in Eurasia (without its westernmost peninsula, Europe). Russia has re-energized its effort to pioneer putting together a Eurasia-wide security architecture, which its sees as a network of close ties among the continent’s existing institutions, bilateral treaties and agreements, logistical and other business projects, technological partnerships, cultural initiatives, and the like.

Within its own neighbourhood Russia will seek closer ties with Belarus within the framework of the Union State; with members of the Eurasian Economic Union and the CSTO, especially Kazakhstan, but also Kyrgyzstan and Tajikistan; with Uzbekistan, Central Asia’s most populous nation. These are the top priorities, linked to what was once called, creating a Russia-led power center in Northern Eurasia. Beyond the countries of the former Soviet Union, Russia will cement its renewed ties to North Korea, and develop its links with Mongolia. In the South Caucasus, next to integrating Abkhazia and South Ossetia with Russia, Moscow will seek to win back influence with Armenia and Azerbaijan, whose relations with Moscow have become badly frayed. There, as in Moldova, Russia’s future influence will largely depend on the outcome of the war in the Ukraine.

Conclusion

With Russia increasingly focused on itself, its policies are likely to be more pragmatic. Moscow’s actions in the wider world – beyond Eurasia – will be guided by its economic interests rather than its geopolitical ambitions. The war in Ukraine has been a harsh but realistic test of Russian capacity to promote and protect its vital interests. The results, which are coming in, are both positive and sobering. The positive side is that Russia has been able to stand up to the maximum economic, financial, political, and information pressure that anyone could have brought to bear on any country in today’s world. Its domestic resilience to that combined pressure has been phenomenal. It has also been able to wage and win a limited conventional war against a medium-sized country supported, armed, trained, equipped, advised, and directed by the United States and the entire Western bloc. Within that struggle, it has been able to retain close friends and partners in the non-Western world. The war itself has provided a powerful stimulus to deal with a number of domestic weaknesses that Russia had been suffering from since the downfall of the Soviet Union. At the same time, Russia has to reckon with the entire West, for the first time in history, lining up against it; Russians have also witnessed what a successful brainwashing campaign could do with the largely Russian-speaking and to a high degree ethnically Russian population of its closest neighbour; Moscow has to take account of the dependence of virtually all countries of today’s world on the U.S. dollar and the Western-centered financial system, and of the immense power of the Western media empire. An analysis of these vulnerabilities points to what needs to be done to make sure that Russia’s security is better protected for the trials that lie ahead: turbulence in the world is unlikely to subside in the foreseeable future.

[1] See statements by U.S. Secretary of Defense Lloyd Austin (Stars and Stripes, April 7, 2022; New York Post, CNN, April 26, 2022). Also, President Biden, according to Brazil’s President Lula da Silva (in an interview with Le Monde on June 4, 2025), “believed that Russia should be destroyed”.

[2] For a detailed and very candid discussion of how Europe is currently viewed in Moscow, see Sergei Lavrov’s remarks at a press conference in Moscow on July 22, 2025, as reported by RIA Novosti News Agency, TASS, RBC and others.

[3] The Concept of the Foreign Policy of the Russian Federation // MFA of the Russian Federation. March 31, 2023. URL: https://mid.ru/en/foreign_policy/fundamental_documents/1860586/ (in Russ.).

[4] All-Russian Center for Public Opinion Polling (VCIOM) poll, released on August 19, 2025 // VCIOM. URL: https://wciom.com/our-news/ratings