Nuclear energy remains one of the most promising areas of cooperation between Russia and African countries. Africa accounts for only 6% of global energy[1], while nearly 600 million people in Sub-Saharan Africa live without access to electricity[2]. Electricity demand in Africa today is 700 terawatt-hours (TWh), and it is expected to doubled by 2040, reaching 1 600 TWh[3].

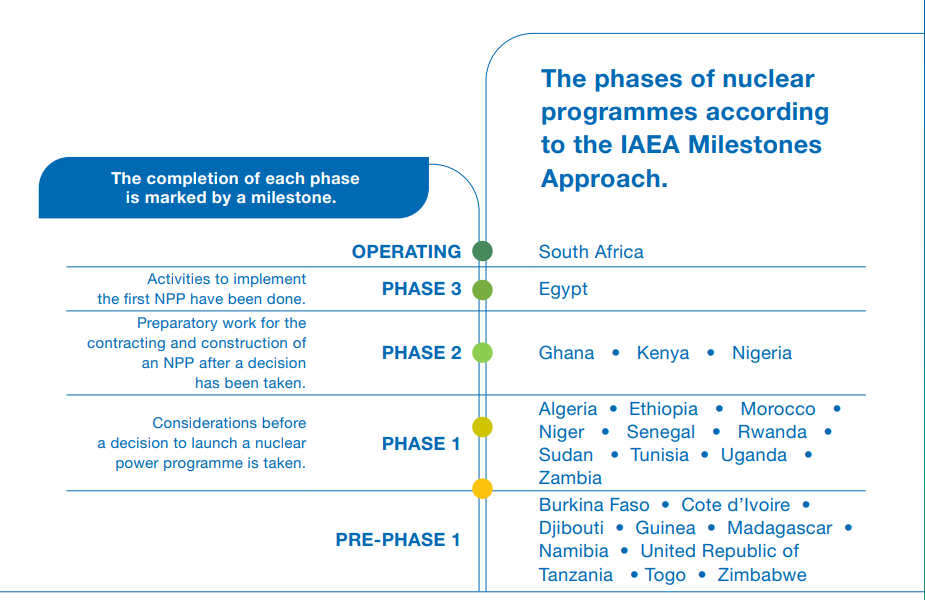

Due to demographic factors, such as rapid population growth, Africa has even greater growth potential. In 2025, Africa’s population is 1.5 billion people, and it is expected to reach 1.7 billion by 2030. Additionally, Africa is gradually industrializing, while more than 600 million people still do not have access to grid electricity. The energy deficit, which is one of the main obstacles to achieving sustainable economic growth in the region, is prompting African governments to seek solutions in the energy sector. According to the Outlook for Nuclear Energy in Africa, published by International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA) in 2025, more than 20 African countries exploring potential of nuclear energy[4].

Is Building a Nuclear Power Plant a Feasible Solution for Africa?

Although African countries are expressing political demand for nuclear energy, the high cost and politicization of such projects are hindering their implementation. The lack of continuity in some countries and the fragility of their governments are also worth considering. These factors pose an obstacle to the consistent development of dialogue in nuclear energy.

There are few countries in Africa that have tens of billions of dollars to spend on building nuclear power plants. As some experts point out, building a nuclear power plant is an expensive project with a long return on investment[5]. Furthermore, many African countries depend on loans from the World Bank and the International Monetary Fund. These loans will undoubtedly prevent an increase in budgetary burdens and will instead promote solutions based on renewable energy sources. For example, a Russian loan is financing 85% of the construction of a nuclear power plant in Egypt, which is the second highest economy in Africa (after South Africa) in terms of GDP[6]. It is even less clear how other African countries interested in building nuclear power plants plan to finance them.

Assessing the prospects for constructing nuclear power plants in Africa, many factors must be considered: insufficient power grid infrastructure development, a shortage of qualified personnel as well as the significant influence of Western companies. Security and safety issues must be given particular attention, while the standard of nuclear safety in all countries must be equal to that in Russia, China, South Korea or any other country which exports its nuclear technologies. There must be no such thing as Egyptian or Burkinabe nuclear security. If an accident occurs in Burkina Faso or Egypt, it will spell the end of nuclear energy for everyone[7]. In this regard, it is also necessary to raise the standards of nuclear education and train specialists from Africa in Russian universities on nuclear specifics. Currently, the number of students and graduates in nuclear fields is growing; however, this does not allow us to consider taking practical steps.

Russia has achieved several successes in its cooperation with African countries in nuclear energy. South Africa was the first African country with which Rosatom began working: Techsnabexport (also known as TENEX) started supplying nuclear fuel to the Koeberg Nuclear Power Plant in 1995. From 2007 to 2009, Rosatom‘s subsidiary Isotope imported molybdenum-99. In 2012, Rosatom opened a regional office for South and Central Africa (a division of Rosatom International Network). However, nuclear energy development opportunities in South Africa are limited in the medium term. The most optimistic scenario is extending the operating life of the Koeberg NPP.

With the launch of the Ed Dabaa nuclear power plant in Egypt, Russia will become the first country in 40 years to build a nuclear power plant in Africa, enhancing its image in the region while allowing Egypt to become an energy hub. More importantly, Egypt’s nuclear power plant is being built with cutting-edge technology. This unique experience will increase Rosatom‘s chances of building nuclear power plants in other countries. There will be a particular impact on interest in Rosatom‘s services among countries in the Middle East and North Africa.

In overview, the construction of nuclear power plants in most African countries may only be in demand in the medium or long term, provided that the industrialization and overall growth of African economies continues. For now, Russia should focus on establishing a long-term presence in Africa by training personnel, participating in the development of sectoral strategies, roadmaps, and action plans, creating the legal and regulatory framework, and establishing Centers for Nuclear Science and Technology as a possible base for further expansion.

Who Wants to Have NPPs?

Algeria, Ghana, Zambia, Kenya, Libya, Morocco, Nigeria, Sudan, and Ethiopia have all expressed interest in building nuclear power plants at various times. However, for some reasons, these plans remain more in the realm of demagoguery and politics than economics. Compared to other African countries, the governments of Egypt and South Africa have been the most consistent supporters of nuclear energy development, although it is worth noting that Pretoria’s interest has recently been called into question by public opinion. For instance, in August 2024, South Africa’s Department of Energy announced its decision to withdraw the tender for constructing 2,500 MW of nuclear facilities, allowing the public to participate in the discussion. Although nuclear energy remains part of South Africa’s plans to ensure energy security, public opinion is an important factor in this area’s decision-making process[8].

As of August 2025, Russia had concluded intergovernmental agreements on cooperation in the peaceful use of atomic energy with 15 African countries: Algeria, Burkina Faso, Burundi, Ghana, Egypt, Zambia, Zimbabwe, Mali, Nigeria, the Republic of Congo, Rwanda, Sudan, Uganda, Ethiopia, and South Africa. Basic agreements governing the general framework for cooperation in the peaceful use of atomic energy have been signed with all of these countries.

Additionally, agreements have been signed with Zambia, Nigeria, and Rwanda regarding cooperation in the construction of centers for nuclear science and technology. However, the agreement signed with Nigeria in 2016 has not yet entered into force. Two more agreements have been signed with Nigeria: one regarding cooperation in nuclear and radiation safety regulations for the use of atomic energy (2021, not yet in force), and one regarding cooperation in designing nuclear power plants (2012, in force).

Floating Nuclear Power Plants (FNPPs): a Reasonable Solution?

On paper, one of the most attractive solutions for reducing Africa’s electricity deficit is the use of floating nuclear power plants (FNPPs). FNPPs are low-capacity nuclear power plants that offer several advantages.

First, FNPPs can be used almost anywhere in the world as long as there is access to the sea. Second, unlike traditional nuclear power plants, FNPPs can meet a specific location’s electricity needs and can be easily transported at any time. Third, customers do not need to decommission nuclear power plants at the end of their life cycles. The handling of spent nuclear fuel is the responsibility of FNPP owners (service providers). Fourth, customers do not need to train a large number of personnel, create expensive infrastructure, or build nuclear power plants over long periods of time. Overall, FNPPs are cheaper than traditional large- and medium-capacity nuclear power plants in terms of total cost. However, despite the positive aspects of FNPPs, there are many uncertainties regarding their prospects, casting doubt on the possibility of their use outside the owning country, particularly in African countries.

The main factor preventing the potential use of FNPPs in the medium term is their limited availability. Currently, only one FNPP exists in the world: the Akademik Lomonosov, which supplies heat and electricity to remote areas of the Russian Arctic and Far East. The emergence of new FNPPs is only a matter of time. Interest in FNPPs is growing, and several countries are developing their own FNPPs. However, the prospects for scaling up FNPP production, let alone using them for commercial purposes, lie more in the realm of long-term planning, though in 2025 there have been statements by Russian officials about plans to export FNPPs by 2030[9].

Another disadvantage of FNPPs is the high cost of the electricity they generate. The costs of using them are justified in regions with difficult climatic and geographical conditions, where FNPPs are one of the most effective means of generating electricity. However, this scenario is inapplicable to Africa, where the shortage of electricity affects the population as a whole rather than specific regions. An exception is the need to electrify specific areas of the country, such as those with concentrated production facilities or mineral extraction sites. It should also be noted that operating FNPPs requires constructing coastal infrastructure that meets all safety requirements. Additionally, it is important to consider the need for nuclear fuel reloading and regular maintenance[10].

The most controversial issue regarding FNPPs is their international legal regulation. For example, problems could arise even with regard to the Akademik Lomonosov, which was built in Russia and then transported for use within its borders. To avoid these problems, the fuel was loaded onto the FNPPs in Murmansk rather than St. Petersburg, where the Akademik Lomonosov was constructed, when the floating power unit passed through the waters of the Baltic Sea[11].

Taking a broader view of this issue in the context of exporting FNPPs to foreign markets and considering the nuclear nonproliferation regime, experts believe that the BOOT-R (build-own-operate-transfer-return) model is the best option. Thus, cooperation should be based on an intergovernmental agreement in which the FNPP-supplying country builds, loads fuel, transports, installs, operates, maintains, and owns the FNPP that generates electricity in the host country. The host country’s responsibilities would be limited to connecting to electrical grids and pipelines, as well as protecting the facility. It would not have access to FNPPs, their technologies, or nuclear fuel[12].

A bilateral agreement between the supplier state and the recipient country, outlining their mutual obligations regarding all legal and organizational issues prior to exporting FNPPs, is necessary to settle any potential legal disputes. Agreements with the IAEA on nuclear nonproliferation guarantees will also be required[13].

From a technical point of view, a floating nuclear power plant is a unique and reliable solution, but its operation is only feasible in certain cases. A number of African countries have expressed interest in acquiring FNPPs, but they will not solve even a fraction of the energy problems currently facing these countries[14]. FNPPs are a new project, however, so it is reasonable to assume that their potential applications, as well as technological improvements, will expand and make them more profitable.

Examining the Cases

Egypt

Several key factors drive interest in nuclear energy in Egypt. First, population growth, urbanization, and industrialization are leading to an ever-increasing demand for electricity. Second, the shortage of drinking water necessitates the use of desalination technologies, particularly in remote areas, which affects energy requirements[15]. Third, nuclear energy is seen as a convenient, cost-effective, and promising energy source. Once implemented, it will supplement traditional energy resources and accelerate technological development, stimulating social and economic progress. Fourth, nuclear energy is the optimal solution for reducing greenhouse gas emissions. This aligns with the goals of the energy transition and is part of the national long-term strategy, “Egypt Vision 2030”[16].

Energy is one of the most intensive areas of cooperation between the Arab Republic of Egypt and the Russian Federation. In 2008, the two countries signed an intergovernmental agreement on the peaceful use of atomic energy. Then, in November 2015, Moscow and Cairo signed another intergovernmental agreement on the construction and operation of Egypt’s first nuclear power plant. The plant is to consist of four power units, each with a capacity of 1,200 MW, and will use Russian technology[17]. Additionally, the Russian government provided export credit for this purpose. As of 2025, Egypt only has one research reactor, the ETRR-2. It has a capacity of 22 MW and was commissioned in 1992. TVEL, a Russian company, was the supplier of nuclear fuel for this reactor[18]. There is also an ETRR-1 research reactor designed by the USSR with a capacity of 2 MW. It was in operation from 1961 to 2010.

The construction of a nuclear power plant in Egypt marks a new stage in technological development for both Egypt and Russia. The plant will be equipped with VVER-1200 reactors, which belong to the “3+” generation and meet the highest international standards for efficiency and safety[19]. The construction of the Ed Dabaa nuclear power plant is of fundamental importance to Egypt due to its scale. It will be the largest power plant project since the construction of the Aswan hydroelectric power plant. The Ed Dabaa Nuclear Power Plant will also provide a solid material and technical foundation of electricity and fresh water for the economic development of sparsely populated coastal areas along the Mediterranean Sea.

In cooperation with the Russian Federation, nuclear fuel supplies for the reactors are being implemented. Contract documents for the delivery of low-enriched nuclear fuel components to Egypt for the ETRR-2 research reactor in Inshas have already been signed, with the first deliveries under this contract made in 2020[20].

One of the most important achievements resulting from the successful completion of the Ed Dabaa Nuclear Power Plant construction and launch is Egypt’s strengthened leadership position among Arab and African countries. This achievement reduces the scientific and technological gap with other countries in the region through knowledge and technology transfer and localization, which contributes to national security. Egypt is already considered a leader in nuclear technology in the Middle East and Africa. The planned commissioning of a nuclear power plant by the end of this decade will only strengthen its status as a regional nuclear science hub.

South Africa

The only nuclear power plant on the continent is located in South Africa – the Koeberg NPP, which was commissioned in 1984 and is owned by Eskom, the state-owned electricity holding company. The NPP was built under the specific conditions of South Africa’s energy independence and access to the technologies needed to develop nuclear weapons.

Since the mid-1970s, South Africa had been actively developing nuclear weapons, focusing its scientific research in atomic energy on this goal. These aspirations were driven by foreign policy factors, such as growing instability in neighbouring countries and mounting tensions with the West. Political and rebel movements operating in neighbouring regions were considered the main external threat[21]. In 1979, the so-called Vela Incident[22] occurred when a flash was detected in the Southern Hemisphere believed to have been caused by the explosion of a low-yield nuclear device. Six nuclear bombs were produced in South Africa while it was developing nuclear weapons, as the country’s top leadership later acknowledged[23].

Radical changes took place in and around South Africa in the late 1980s and mid-1990s, affecting the nuclear industry. South Africa reduced its presence and influence in neighbouring countries and regions. Notably, from 1988 to 1990, South Africa renounced military intervention in Angola and control over Namibia. Then, political transformations occurred within South Africa. Ultimately, these changes resulted in the loss of power by the regime that had ruled the country for the past thirty years. These reforms included a review of foreign policy, which caused South Africa to lose interest in nuclear weapons. In 1989, South Africa officially renounced and disposed of its nuclear weapons.

South Africa was the first African country with which Rosatom began cooperation in 1995 when Techsnabexport started supplying nuclear fuel to the Koeberg NPP. For most of the past decade, the construction of a nuclear power plant in South Africa remained Rosatom’s key project in Africa. On September 21, 2014, Russia and South Africa signed a strategic partnership agreement on nuclear energy and industry. This agreement included preparations for constructing power units with a total capacity of over 9 GW and a cost of at least $70 billion[24].

In South Africa, the prospect of concluding a deal with Russia regarding nuclear power units has drawn sharp criticism from experts, opposition parties, and some government officials. South Africa’s largest opposition party, the Democratic Alliance, publicly accused President Jacob Zuma of secretly signing an agreement with Russia to build nuclear power plants. Although Zuma officially denied the allegations, they played a significant role in shaping the image of a corrupt regime and its subsequent defeat in the internal party struggle. Political dialogue in South Africa is inclusive. Any major deal involving foreign participation requires a broad discussion of the interests of many actors, both formal and informal.

In March 2017, Pravin Gordhan, the South African finance minister and a vocal opponent of the large-scale program to build new nuclear power plant units, was dismissed. On April 6, 2017, the High Court of the Western Cape Province in South Africa ruled that the 2015 tender process for the construction of nuclear power units with a total capacity of 9.6 GW was invalid, thereby invalidating the relevant intergovernmental agreements with Russia, the United States, and South Korea. The court also ordered parliamentary hearings on the project to be held[25]. The lawsuit was filed by Earthlife Africa, a non-governmental volunteer organization, and the non-profit Southern African Faith Communities’ Environmental Institute.

The collapse of the Rosatom-South Africa nuclear deal has damaged the foundation of Russian-South African relations. The project had been a pillar of the bilateral agenda for nearly a decade.

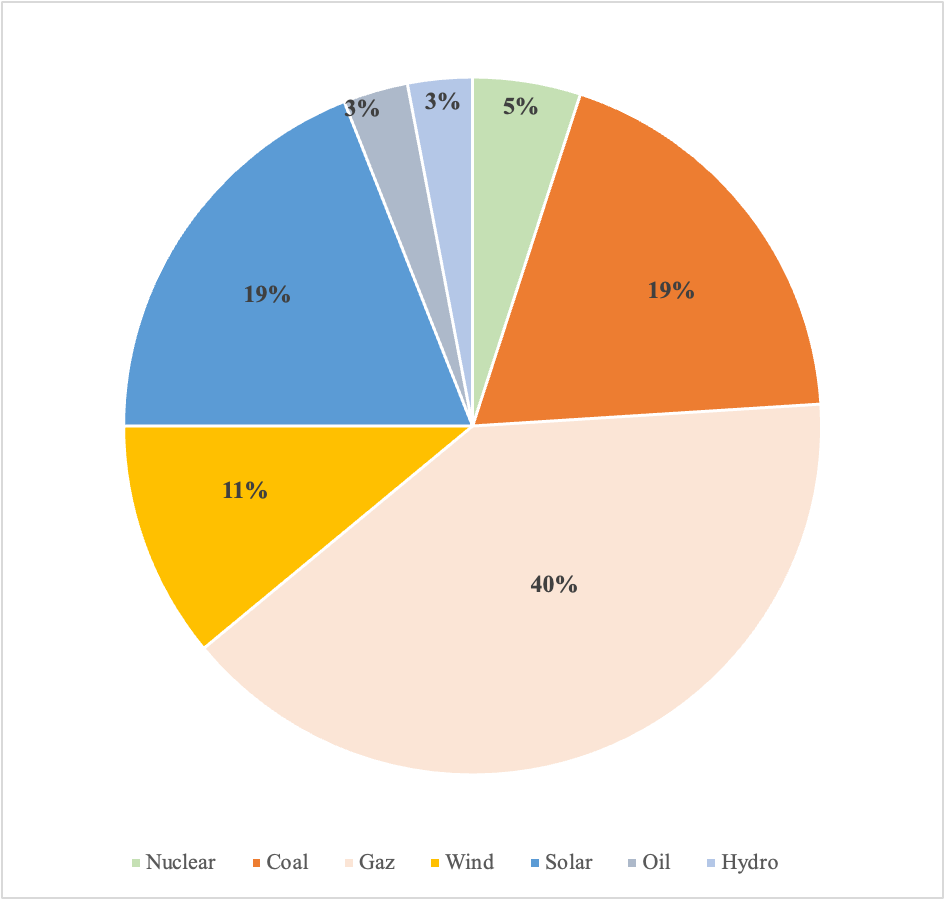

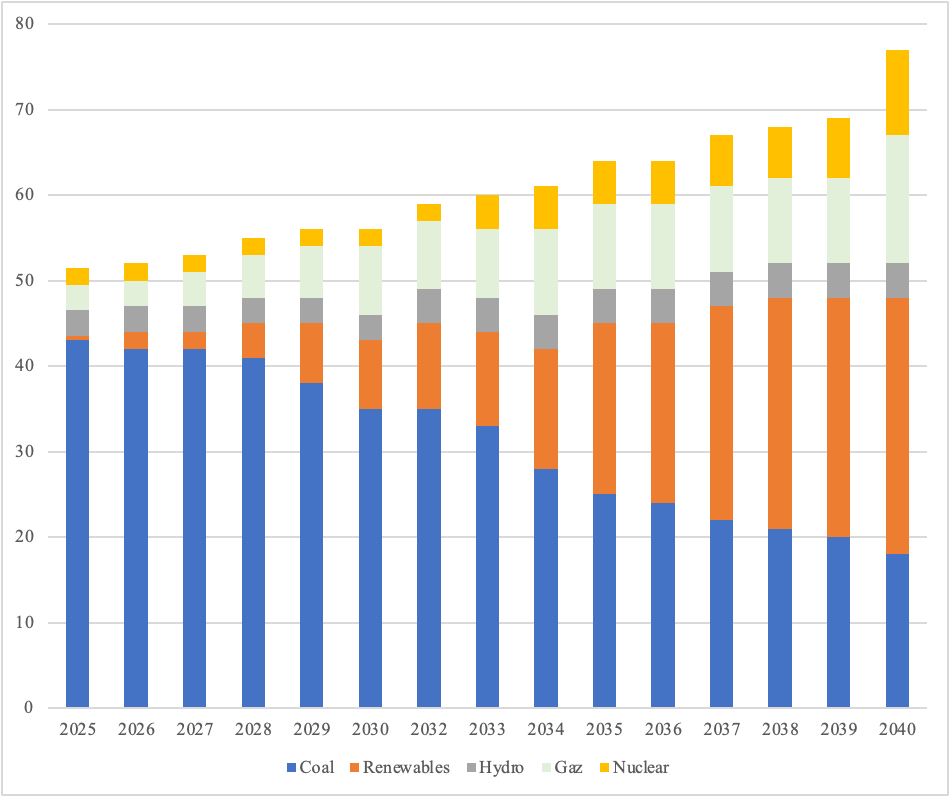

Overall, it should be noted that the potential for developing nuclear energy in South Africa is limited in the medium term. The most optimistic scenario is extending the operating life of the Koeberg nuclear power plant. South Africa’s economic conditions dictate the need for new wind farms, solar power plants, and gas-fired generation facilities. Deviating from these efforts, especially circumventing South Africa’s adopted energy strategy, would be a waste of resources. However, South Africa is considering building new nuclear power plants to diversify its energy sources[26]. Such a strategy is linked to the systematic phase-out of coal-fired power plants, which have historically met most of the country’s electricity needs, and the transition to the wider use of renewable energy sources. Though, the prospects of such initiative seem very dim.

Conclusion

Energy shortages are one of the main obstacles to sustainable growth in African economies, so African governments are demonstrating a growing demand for any energy solutions. They are turning to the experience of proven contractors, particularly in the nuclear sector.

Russia and Rosatom have undoubtedly achieved some success in African countries: the expansion of the legal framework for the peaceful use of nuclear energy and the construction of nuclear power plants in Egypt are the result of Russia’s long-standing work in this area.

However, demand for nuclear power plant construction services in most African countries will only be in the medium to long term subject to the development of industrialization and overall growth of African economies. Should we expect large dividends from Africa? Unlikely. At the same time, this doesn’t mean cooperation should be curtailed. On the contrary, the contacts and connections being established between our countries today will soon serve as a solid foundation for the implementation of ambitious projects.

[1] Africa – Countries & Regions. International Energy Outlook // IAEA. URL: https://www.iea.org/regions/africa

[2] Mission 300: Overview // World Bank. URL: https://www.worldbank.org/en/programs/energizing-africa/overview

[3] Africa Energy Outlook 2019. International Energy Outlook // IAEA. URL: https://www.iea.org/reports/africa-energy-outlook-2019

[4] Outlook for Nuclear Energy in Africa 2025 // International Atomic Energy Agency. URL: https://www-pub.iaea.org/MTCD/Publications/PDF/p15896-PAT-011_web.pdf

[5] Nuclear Renaissance: Russian Specifics and Global Context. Security Index №2 (85), Vol.14. URL: https://pircenter.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/10/Иванов-В.Б.-Каграманян-В.С.-и-др.-Ядерный-ренессанс-Российская-специфика-и-глобальный-контекст.pdf (in Russ.).

[6] African countries with the highest Gross Domestic Product (GDP) in 2025 // Statista. URL: https://www.statista.com/statistics/1120999/gdp-of-african-countries-by-country/

[7] Viktor Murogov: “Russia is “doomed” to develop nuclear energy” // Security Index №3, 2005, pp. 21-30. URL: https://pircenter.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/11/Ядерный-Контроль-№77-2005.pdf (in Russ.).

[8] South Africa pauses nuclear procurement process // World Nuclear News. August 16, 2024. URL: https://www.world-nuclear-news.org/articles/south-africa-pauses-nuclear-procurement-process

[9] Rosatom wants to deliver the first floating nuclear power plants abroad in 2030 // Interfax. May 19, 2025. URL: https://www.interfax.ru/business/1026435 (in Russ.).

[10] FNPPs: an expensive toy or an efficient station? // Neftegaz.ru. August 13, 2020. URL: https://neftegaz.ru/news/energy/625777-vyrabatyvaemaya-na-pates-akademik-lomonosov-elektroenergiya-okazalas-znachitelno-dorozhe-sushchestvu/ (in Russ.).

[11] Nuclear fuel is to be loaded into the reactors of a floating nuclear power plant at the base in Murmansk // RIA Novosti News Agency. July 21, 2017. URL: https://ria.ru/20170721/1498928221.html (in Russ.).

[12] Lysenko M., Bedenko V., Dalnoki-Veress F. Legal Regulations of Floating Nuclear Power Plants: problems and prospects. Moscow Journal of International Law. 2019. №3. P. 59–67.

[13] Ibid.

[14] Semenov E. On the prospects of floating nuclear power plants in Africa // PIR Center. February 9, 2024. URL: https://pircenter.org/editions/o-perspektivah-plavuchih-ajes-v-afrike/ (in Russ.).

[15] Lorenzini M. Why the nuclear power plant in Egypt can be considered a long-term victory for Russia // Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists. December 20, 2023. URL: https://thebulletin.org/2023/12/why-egypts-new-nuclear-plant-is-a-long-term-win-for-russia/

[16] The National Agenda for Sustainable Development Egypt’s Updated Vision 2030 // Ministry of Planning and Economic Development (Egypt). URL: https://mped.gov.eg/Files/Egypt_Vision_2030_EnglishDigitalUse.pdf

[17] Russia signed an agreement on the construction of the first nuclear power plant in Egypt // RBC. November 19, 2015. URL: https://www.rbc.ru/rbcfreenews/564deeea9a79473987063238 (in Russ.).

[18] Rosatom supplies fuel components for research reactor to Egypt // TASS. November 22, 2022. URL: https://nauka.tass.ru/nauka/16397393 (in Russ.).

[19] Safety system was delivered from Russia to the El-Dabaa nuclear power plant in Egypt // RIA Novosti News Agency. July 2, 2024. URL: https://ria.ru/20240702/egipet-1956950962.html (in Russ.).

[20] TVEL supplies fuel components for research reactor in Egypt // Neftegaz.RU. February 8, 2024. URL: https://neftegaz.ru/news/nuclear/817443-tvel-postavit-komponenty-topliva-dlya-issledovatelskogo-reaktora-v-egipte/ (in Russ.).

[21] The Nuclear Principality // Atomic Expert. URL: https://archive.atomicexpert.com/page1252866.html

[22] Vela Incident – unidentified double flash of light detected by an American Vela Hotel satellite on 22 September 1979 near the South African territory of Prince Edward Islands in the Indian Ocean, roughly midway between Africa and Antarctica – Editor’s note.

[23] South Africa Says It Built 6 Atom Bombs // The New York Times. March 25, 1993. URL: https://www.nytimes.com/1993/03/25/world/south-africa-says-it-built-6-atom-bombs.html

[24] Russia and South Africa signed an intergovernmental agreement on strategic partnership in the nuclear energy sector. // Nuclear Energy. September 23, 2014. URL: https://www.atomic-energy.ru/news/2014/09/23/51669 (in Russ.).

[25] South African court blocked agreement with Russia on construction of nuclear power plant // RBC. April 26, 2017. URL: https://www.rbc.ru/business/26/04/2017/59008fb59a7947a565925081 (in Russ.).

[26] South Africa pushes ahead with new Cape nuclear plant // Reuters. August 8, 2025. URL: https://www.reuters.com/sustainability/boards-policy-regulation/south-africa-pushes-ahead-with-new-cape-nuclear-plant-2025-08-08/