Julia Melnikova: Recent years in context of Russian-Chinese relations have been eventful. First and foremost, Moscow and Beijing celebrated the 75th anniversary of diplomatic relations in 2024. The Russian President visited China – as his first foreign trip since the reelection. The coordination and elaboration of Russian and Chinese positions in preparation for the BRICS summit in Kazan was also visible. What of the past events do you remember most?

Andrey Denisov: Much has happened in Russian-Chinese relations. To list them all would take a very long time. But I would note the following. First, they were very intense – in terms of both personal contacts and all kinds of exchanges, partly for objective reasons. Our activity in the West has understandably diminished. Now the focus is, of course, on the South and the East – that is, the countries of the Global Majority. This is entirely natural, and China is one of the poles of the modern world. But the development of bilateral relations, even apart from the international context, also leaves a certain imprint and requires more frequent communication.

For example, we’ll count from the beginning of 2013 – I began my term as ambassador, Xi Jinping was first elected President of China in March 2013, and Vladimir Putin began his presidential term a year earlier. Since then, there have been several dozen meetings between our leaders, both in Russia and China, at bilateral events and, as we say, in third countries, on the sidelines of various international forums. All of them were rich in content, never routine or formal.

As you know, such meetings are often called meetings on the move. Although, in fact, they are actually sitting down. In 2024, for example, three such meetings took place, and this number includes full-fledged visits. However, there could have been as many as five. As I already mentioned, our leaders also usually hold meetings on the sidelines of international forums.

The APEC summit in Lima, Peru (November 15-16, 2024), and the G20 summit in Rio de Janeiro, Brazil (November 18-19, 2024), took place. The President of China participated in both forums, and Russia was represented by Foreign Minister Sergey Lavrov.

However, here’s what’s important: at the meeting of our ministers in Rio de Janeiro, in addition to President Xi Jinping, the Chinese delegation naturally included the Minister of Foreign Affairs, who held a separate meeting with Sergey Lavrov. Following this meeting, the Chinese Ministry of Foreign Affairs published a very revealing press release. These aren’t just words from a press conference or answers to journalists’ questions. This is an official document of the ministry.

It stated that the ministers, having met in Rio de Janeiro, discussed in detail the agreements reached by the leaders of our states at the BRICS summit in Kazan, where, as was again stated, almost verbatim, it was said that the leaders discussed the further deepening of the strategic partnership at the next stage of development.

Statements in documents like these, especially when presented by China, are never random. What actually happened is that the leaders of our countries, meeting over the course of a year, outlined certain milestones and prospects for the future. This was probably the most important thing.

…The main written outcome of the Russian-Chinese “summit” (May 8, 2025) is the “Joint Statement”. The very first pages of this lengthy document contain important provisions, some of which have not previously appeared in similar texts. Specifically, it speaks of “the military brotherhood and traditions of mutual assistance between the two countries, forged during the Second World War, as the solid foundation of our relations today”. It mentions the “spirit of eternal good-neighbourliness and friendship”. It emphasizes the “broad commonality of national interests in the long-term: historical perspective”. Finally, it states that Russian-Chinese relations possess “unique strategic self-sufficiency and a powerful internal driving force”.

These and other formulations reflect historical continuity and simultaneously look to the future, which in itself deserves close attention. These are not simply solemn rhetoric. These are commitments that the parties intend to adhere to, taking into account the highest political level of adoption. Their weight is particularly compelling against a global political backdrop that is far from stable and orderly.

Andrey Denisov

10th International Conference “Russia and China: Cooperation in a New Era”

May 30, 2025

https://russiancouncil.ru/analytics-and-comments/analytics/mnogopolyarnost-i-mnogostoronnost-razdvoenie-edinogo-ili-dva-v-odnom/

Of course, this isn’t exactly a convergence of the two countries’ positions on international affairs. They were already quite close – though they weren’t entirely identical, because we are two great powers with our own interests, our own areas of priority. And we’re not part of any alliance, so we have no alliance obligations that would commit us to unquestioningly adhere to certain statutes. We have nothing of the sort. Nevertheless, life itself is pushing us to further align our positions on the international situation. This is perhaps the most important thing.

Julia Melnikova: There’s no doubt that developing strategic cooperation with China is an axial direction of Russian foreign policy, embodying a Pivot to the East that has been ongoing for over a decade. To what extent is this a systemic trend? Will changing foreign policy conditions impact the development of the Russian-Chinese partnership?

Andrey Denisov: The situation is truly challenging – for us, for China, and for the entire world. We, Russia, inevitably adapt to changes in the international situation. China’s policy, however, is primarily focused on maintaining some kind of stability. Beijing has a stake in this. China is one of the protagonists and key participants in globalization. Globalization, which has, to a certain extent, reached a dead end, but will probably be revived with time – because such is, perhaps, the fate of humanity: it will either, so to speak, solve problems together, or simply perish. But these are philosophical generalizations.

At this point in history, our discord is impossible – I’m absolutely convinced of that. This is primarily due to the difference in approach between “our people”, as they say, and those on the other side of the counter or the other side of the barricade. Because, after all, on the other side, the world is black and white: “Either you’re with us, or you’re with them”.

Mao Zedong’s contribution to Marxist thought lies in his so-called “theory of two distinct types of contradictions”[1]. There are contradictions between us and our enemies – in common parlance, antagonistic ones. And then there are, as he put it, contradictions within the people. This means contradictions with those who simply hold different views, but are nonetheless not our adversaries. And we simply need to work with them, or at least get along with them.

Our position boils down to this approach. We’re not calling for everyone to support or share our position on the Ukrainian conflict, for example. We’re more counting on understanding our motives, our concerns about security and the situation of the Russian-speaking majority – I insist that this is a majority in Ukraine, not a minority. These are well-known positions. And if countries don’t show what’s called open support – and China, by the way, doesn’t either, since it also shows understanding, it doesn’t express support directly – then we believe this is a benevolent stance toward our country.

The Americans behave completely differently. They say that if you don’t condemn “Russia’s aggression”, then you’re supporting it. That’s all. And they told China something like this: you should stand on the “right side of history”, so that we can then gather all our forces and throw them at you.

But the Chinese have already seen this – it’s impossible to hide. Therefore, there are objective factors that force us to respond to emerging challenges from a common starting point.

Vladimir Legoyda: Continuing with the topic of Russian-Chinese cooperation, the idea of a strong state is, in general, common to both us and the Chinese. But as a former Americanist, I remember we always said that Americans differentiate between the state and the people. For us, our Homeland, people, and state are practically identical concepts. How similar are we to the Chinese in this regard?

Andrey Denisov: In general, they’re probably similar. A strong state is needed everywhere. If in football they say “the order beats the class”[2], then at the level of state building this is even more true. You can have scientific and technological achievements and a high level of education, but this won’t help you survive if the state doesn’t function effectively. And if it does, then everything else can be built.

If there is a difference between us and the Chinese, it was more in the realm of ideology, and now that has disappeared. For example, half a century ago, when I first came to China as a student, there was a campaign of criticism of Lin Biao[3] and Confucius. In particular, they criticized his [Confucius’s – Editor’s note] expression, “Míng fù guó qiáng” [Chinese: 民富国强] – “the people are rich, the state is strong”. I asked, which is correct? The correct translation is the opposite: “Míng qiáng guó fù” [Chinese: 民强国富] – “the people are strong” (primarily ideologically), “the state is rich”. The question arises: for whom, exactly, is it rich? But there was no answer to this question; it was never posed in principle. It was believed that it didn’t matter who the people were, as long as the state was rich. That is, the priority of the state over the individual was probably as high as it was in our country in those years. And then, gradually, it somehow shifted.

But we are in the middle between East and West. For example, China has never had large landed estates, and therefore no hereditary aristocracy. The Chinese language does have words like “baron”, “count”, and so on, but these are court, not property titles. They are not landlords. In China, the state has always been the core of social organization. The emperor, ruling by mandate of Heaven, appointed viceroys whose job it was to keep the population subservient and pay taxes. This is precisely why the attitude toward the state and toward officials in China is still significantly more respectful than even ours, let alone in bourgeois democracies.

China has showbiz stars, astronauts, more billionaires than the US, and bloggers with an audience of 200 million. But the main criterion of social status is proximity to the state. A government official still ranks above all of these.

In China, irrigated agriculture was the foundation of the economy. To establish it, armies of labor were needed, just as in Egypt during the construction of the pyramids. This could only be accomplished through state efforts. In Europe, things were different. We, of course, adopted some things from Europe and ended up somewhere in the middle. But still, like China, we need a strong state. That’s without a doubt.

Julia Melnikova: Let’s discuss the UN, which is currently going through difficult times. Given the extreme uncertainty we’re experiencing, there’s a feeling that if reform of the entire UN system were to begin, we could face chaos in international security and communications for all nation states. How does China view the UN’s current role? How important is this issue for it? And do Russia and China share similar positions on UN reform?

Andrey Denisov: I’d start by noting that the UN is truly a vast, complex system. There are so-called special agencies, more than a dozen of them, each comprising various divisions and mechanisms that carry out their own specific activities. There are peacekeeping operations whose budgets exceed the regular budget of the UN itself. In short, there’s a lot going on within those two letters in English (UN), or three letters in Russian (ООН), or three characters in Chinese (联合国)… It’s worth remembering, first of all, the English proverb: if it ain’t broke, don’t fix it.

The system truly needs reform, but it hasn’t broken down. It’s perfectly clear that the UN continues to play an important role as an organization with universal legal personality, which cannot be replaced. And, in my opinion, even the most ardent critics of the UN or the most radical advocates of its reform cannot help but think that while it’s easy to destroy, creating something new isn’t just difficult, it’s probably downright impossible in today’s world.

When people talk about UN reform, they often think primarily of the Security Council (UNSC): expanding, maintaining, or eliminating the veto power, the categories of permanent and non-permanent members, and so on. It’s as if the entire world has truly converged on this focus. In reality, as we see, the system is complex and expensive. And perhaps we should begin not with this, but with the effectiveness of the considerable resources invested in UN operations.

Regarding China: China is a permanent member of the UNSC, values its permanent membership very highly, and tries to use it whenever possible to advance its general line in foreign affairs. Furthermore, China is very cautious about various options for expanding the Security Council, especially in the permanent membership category. I can’t say that our positions here are entirely aligned. And, again, that’s normal. We are, after all, large countries, and we have specific interests and our own views.

…As the first founding member to have signed the UN Charter and a permanent member of the UNSC, China has always firmly upheld the authority of the United Nations and supported the central role of the United Nations in international affairs. <…> China always calls for win-win cooperation, opposes zero-sum game, and advocates making the pie of cooperation bigger together for the benefit of more countries and people. <…> In a world fraught with changes and turbulence, countries expect the United Nations to effectively play a leading role in addressing global challenges and the Security Council to shoulder the important responsibility of maintaining international peace and security under the UN Charter. The Security Council reform is an organic part of a comprehensive reform of the United Nations.

China supports the two Co-chairs to promote steady progress in the reform of the Security Council in the right direction from the long-term development of the United Nations and the common interests of all member states, increasing the representation and voice of developing countries, giving more small and medium-sized countries the opportunity to participate in decision-making, and enabling all member states to benefit from the reform.

Wang Yi

Foreign Minister of the PRC

February 28, 2024

https://www.fmprc.gov.cn/eng/wjb/wjbz/hd/202403/t20240318_11261742.html

Incidentally, we don’t always vote the same way in the UNSC. I don’t recall, for example, us voting “for” and China voting “against”, but there have been times when we voted “for” and China abstained, or vice versa: China voted “for”, and for some reason we abstained. The reason, incidentally, is always well-founded and is always communicated to our partners.

In short, China, fundamentally committed to stabilizing the international system as a whole, is pursuing this line at the UN as well. We shouldn’t expect any revolutionary calls from China in this regard.

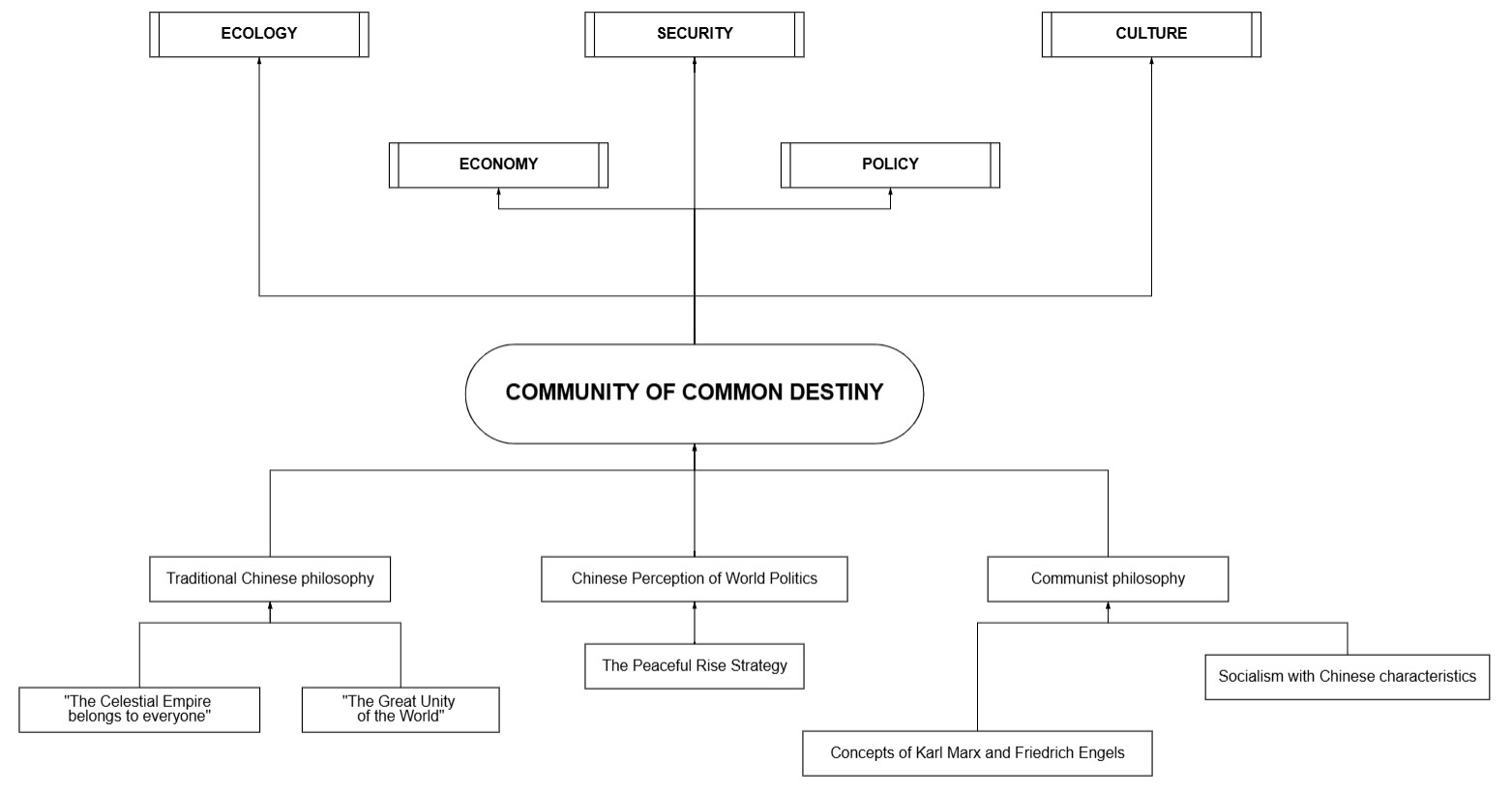

Julia Melnikova: In parallel with its role at the UN, China is also actively developing its own foreign policy doctrine. The idea of a “Community of Common Destiny”[4], global initiatives in security, development, and civilization… In your view, how does this system complement or perhaps differ from the Russian idea of a multipolar world? And who is the target audience for China’s foreign policy conceptualization?

Andrey Denisov: Let’s talk about the target audience right away. Chinese foreign policy doctrines and initiatives are, as the Pope’s encyclicals say, Urbi et orbi – that is, addressed to the entire world. But they are probably primarily addressed to that same Global Majority, because Beijing expects understanding and a favorable attitude toward these initiatives. Incidentally, they are of a general nature. And, in principle, there is no element of conflict. If this is a global development initiative, then it is about the right to development for all, regardless of political systems, external influences, and so on. If it is about global security, then it is for all, not selectively.

There is a Global Civilization Initiative[5] that essentially presupposes both of the above. That is, global civilization is shaped by a wide variety of countries and peoples, and it develops historically, and there is no need to artificially interfere with this process for some far-fetched or ideologically driven reasons.

There are some more concrete proposals, like the well-known “One Belt, One Road” megaproject. This is more of a material concept, as we’ll call it. None of them, in my view, have any potential for conflict, and none of them isolate anyone from what they call their essence. Essentially, all of these Chinese initiatives are, in one way or another, inviting.

Beijing has realized its strength. You see, over the past few decades, China has been building its, well, literally, muscles faster than it has been able to rewire its consciousness to match those muscles.

About five or six years ago, China overtook the US in GDP, calculated using purchasing power parity. We understand that this is a misleading indicator, and we shouldn’t rely on it. If we use the traditional calculation method, that is, using the exchange rate, then for the US, either way, because it uses the dollar, yes, so purchasing power parity and the exchange rate are the same indicator. Not so for China. Based on the exchange rate, it still lags behind, but it’s already somewhere on par with the US, and these two countries are significantly ahead of all other countries in the world. That is, those in third, fourth, and fifth place are a significant distance behind the two global leaders, which is why China has become more active.

This was even evident in the Ukrainian Crisis: China put forward its own initiative, its own regulatory plan, which, in terms of approaches – perhaps not the specific content, but the approaches there – are precisely about ensuring security for all participants, that’s the main thing, and that’s what, in principle, seems so promising to us.

Recently, China joined forces with Brazil and formed a joint settlement plan, which is being offered primarily to the global majority because it is being met with understanding. One hundred and fifty countries are, to varying degrees, receptive to such Chinese initiatives regarding the Middle East and its crises. I say “renewed numbers” because the Syrian crisis[6] has been added to the Palestinian-Israeli, Israeli-Lebanese, and Israeli-Iranian conflicts, effectively eclipsing all others.

China has made relevant statements regarding the Syrian crisis, and perhaps in the past, Beijing perhaps delayed publicly expressing political opinions a bit. Now the situation has changed. China feels it is an active participant, not just entitled but obligated to engage in resolving international conflicts.

We, at the very least, don’t object to this, because we don’t have to agree with China’s approach in every way – we don’t coordinate it – but the underlying thinking is quite close to our hearts. We understand China’s motives in putting forward its initiatives.

[1] The idea was first expressed in the Mao Zedong’s essay “On Contradiction” (1937) and based on statement that all movement and life is a result of contradiction. Mao further develops the theme in his speech “On the Correct Handling of Contradictions Among the People” (1957). This idea also forms the philosophical underpinnings of the ideology of Maoism – Editor’s note.

[2] A popular expression attributed to one of the founders of Soviet football, Nikolai Starostin (1902-1996). It means that a well-established system and discipline are more effective than the individual skill of isolated, disorganized individuals – Editor’s note.

[3] Lin Biao (1907-1971) – was a Chinese political figure and Marshal of the People’s Republic of China, considered Mao Zedong’s right-hand man and successor until his death in a mysterious plane crash over Mongolia. He was posthumously declared a traitor and expelled from the Communist Party of China. – Editor’s note.

[4] Also known as “Community of Common Destiny for Mankind”, “Community with a Shared Future for Mankind” and “Human Community with a Shared Future”. The slogan was first used by Hu Jintao and has been frequently cited by Xi Jinping to describe a stated foreign-policy goal of the PRC. First of all, the aim of creating a “new framework” of international relations which would promote and improve global governance – Editor’s note.

[5] This is a diplomatic initiative of the PRC, proposed in 2023. Its goals include strengthening mutual understanding among peoples, promoting the development of civilization, promoting equality and mutual learning among civilizations through dialogue, and countering the concept of the superiority of one civilization over others – Editor’s note.

[6] This refers to the collapse of the Bashar al-Assad regime and the transfer of power into the hands of the armed opposition led by Ahmed al-Sharaa in December 2024. For more information on the development of the key crises in the Middle East, see Chapter 11 of this Yearbook. – Editor’s note.