Eseniia Kosulina: About fifteen years have passed since the Arab Spring, but its consequences are still felt in the region. What important lessons, in your opinion, did the Middle Eastern states learn from it? Have they become more resilient to modern security challenges or, on the contrary, more vulnerable?

Vitaly Naumkin: Fifteen years ago, when my colleagues and I began to comprehend the new turbulent transformation processes that had begun in a number of countries in the Arab East, we preferred to call them the Arab Awakening rather than the Arab Spring, although this term is also difficult to call impeccable from today’s perspective. What happened to the states in which the situation seemed quite prosperous and the regimes stable? Of course, not long ago in Egypt, for example, there were “bread riots”, and in this same country and a number of other states, the activity of radical Islamist organizations had long since begun to grow. The ruling elites “slept through” the preservation of the previous factors of protest movements and the emergence of new challenges, including multiple imbalances in institutional development, which in turn created the ground for ongoing internal conflict.

As a result, we see that today external stabilization seems rather shaky, and the problems unresolved: it is enough to mention the difficult situation in the area of interethnic and interfaith relations or the failure of the outdated practices of the ruling regimes, which often not only fail to untangle the conflict knots, but sometimes even reinforce the lines of confrontation. The example of the collapse ofthe revolutionaryBaathist regime in Syria speaks for itself.

Eseniia Kosulina: How can Middle Eastern countries join forces to strengthen collective security and counter common threats? What is the main obstacle to regional stability today?

Vitaly Naumkin: The states of the Middle East are clearly interested in creating a system of collective security in it, which would facilitate the unification of efforts in countering common threats to their security. In the context of this interest, Russia has proposed its draft Concept of Collective Security[1] for consideration by the parties. I will not presume to judge the merits of this document, which Moscow is not imposing on anyone, only offering its advisory assistance. However, the Institute of Oriental Studies of the Russian Academy of Sciences, within the framework of “second track diplomacy”, has taken upon itself the task, with the approval and assistance of the Russian Foreign Ministry, of organizing a series of meetings of high-level representatives and experts from interested states and international organizations (the UN, LAS, GCC, African Union, etc.) recommended by the relevant governments to consider Russian proposals.

Several such meetings were held in Moscow, and the last one was attended by about 40 experts from 19 countries, not counting Russia, as well as a number of Western countries. Both the similarity of approaches to the urgency of developing the foundations of the above-mentioned system and serious disagreements between the participants were revealed. Thus, the representative of the UAE, for example, believed that the majority of the participants allegedly ignored “Iran’s expansionist policy in the region”. The expert narrowed the boundaries of the region to the Gulf zone itself, excluding Israel, which has nuclear weapons, and expanding them to Lebanon, and this point of view was supported by Bahrain.

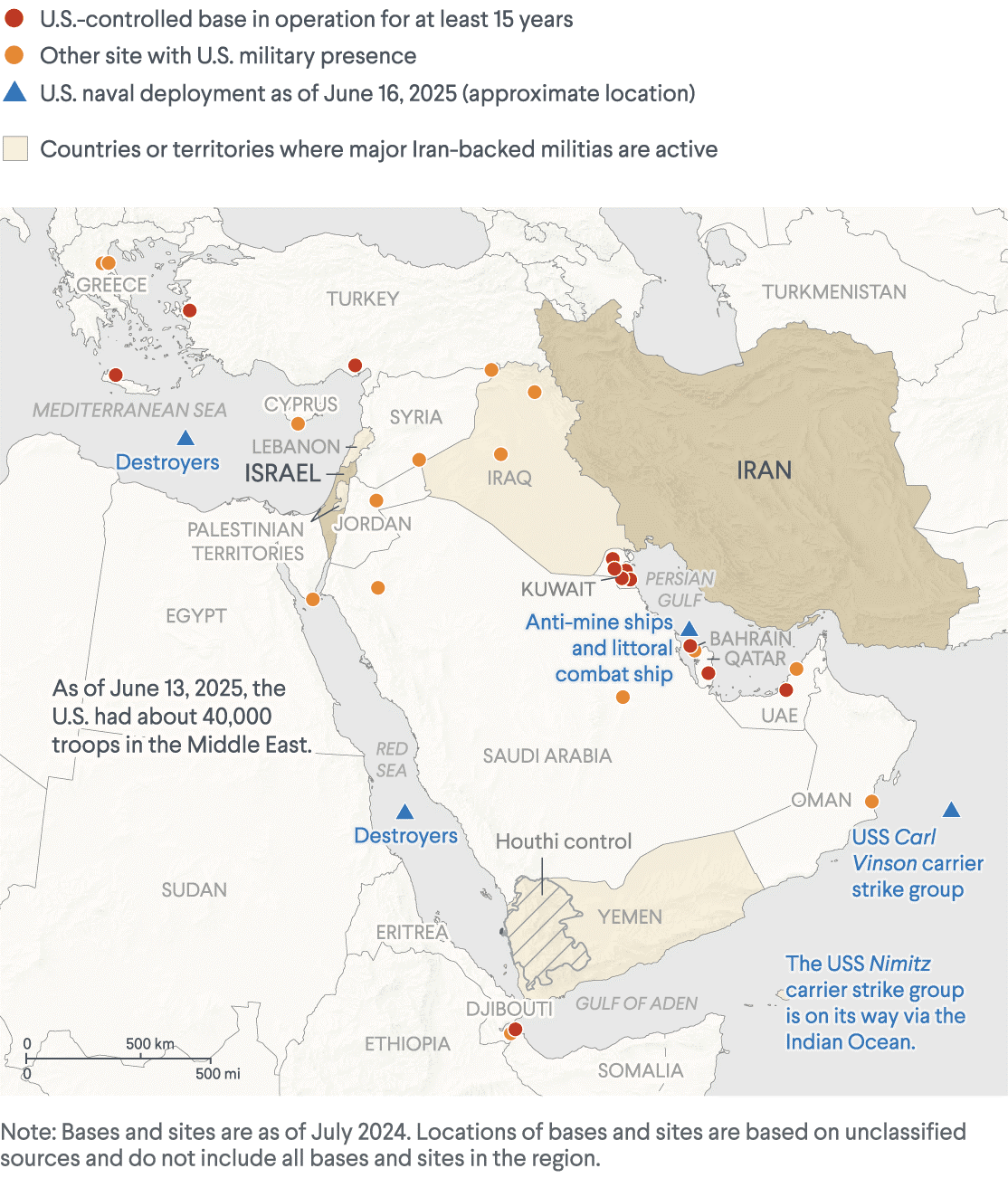

The Iranian representative at the second meeting noted the insufficient attention paid by the Russian draft Concept to the “destabilizing role of the United States”. He also defended the view that the Gulf zone is a small area of water in which there are “too many foreign ships”.

The Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action (JCPOA) topic was also touched upon, with participants noting the split in the GCC, which manifested itself at that time in attempts to isolate Qatar at the initiative of the Saudi Arabia and the UAE. Discussing the possibilities of regional cooperation to address the problems of resource shortages, ecology, and socio-economic imbalances, a number of participants acknowledged the severity of these problems (Bahrain, Kuwait, Yemen), but noted the “disunity and selfishness” of their regional neighbours. An expert from the UAE took advantage of the discussion on this topic to accuse Iran of appropriating water resources from Iraq, without criticizing Türkiye’s similar actions in relation to Syria and Iraq (of which it is often accused by others), not to mention Israel. Overall, it was not possible to reach a consensus.

Experts highly appreciated Russia’s role in striving to help countries in the region in their efforts to form a system of collective security in the region and consolidate counteraction to common threats.

Eseniia Kosulina: Over the past decade, the US has not abandoned attempts to build a collective security system in the region similar to NATO, but has failed each time. What is the key problem with the American project? Is there a demand for the formation of alternative security projects today, and who is more interested in them?

Vitaly Naumkin: The problem with the US is that the implementation of their ideas and projects is seen in the Arab East as a result of pressure, not independently made decisions. These states prefer to demonstrate their independence by putting an end to all vestiges of colonialism.

Eseniia Kosulina: How do you assess the current role of the League of Arab States in preventing and resolving conflicts in the Middle East? Does the concept of Arab Unity continueto serve as a link between the Arab countries of the region or is it time to reform the organization?

Vitaly Naumkin: Unfortunately, the role of the LAS is clearly insufficient. Contradictions between member states often hinder the adoption of consolidated decisions, which requires first resolving conflicts and at least mitigating contradictions, often secondary and inspired by the opponents of the Arabs.

Eseniia Kosulina: How balanced are the interests of the League of Arab States and the Gulf Cooperation Council? Do you think that the Gulf monarchies are trying to distance themselves from the rest of the Arab world and create their own security system? What is the danger of such trends?

Vitaly Naumkin: No, I don’t think so. The LAS and the GCC differ not only in the scale of their activities, but also in their main content. In the GCC, the key areas of cooperation in recent years have become security (both in terms of countering external threats and in terms of countering attempts to destabilize the domestic political situation) and economic cooperation and integration – ultimately, this is an integration grouping. It is no coincidence that the question of its transformation from a Council into a Union has long been discussed in the GCC countries.

At the same time, the LAS is not and has never been an integration grouping; it is aimed at shaping the regional space of Arab countries. Accordingly, it has never reached the point of creating a unified security system (although such ideas have been discussed at various times). So the integration of the GCC, including in security matters, seems to me to be quite normal and does not contradict the activities of the LAS.

Eseniia Kosulina: Let’s continue the topic of regional organizations. The escalation of the conflict between Iran and Israel in June 2025 once again provoked a discussion about the need to gradually create a nuclear-free zone in the Middle East. Is there a chance to implement this project? How can regional organizations help speed up this process?

Vitaly Naumkin: This idea has long been on the agenda, and Russia remains its consistent supporter. At the same time, the chances of its implementation in the entire Middle East today seem not very high – primarily due to the numerous security dilemmas in the region. More realistic was the discussion of a nuclear-free zone in the Persian Gulf region, but now the escalation you mentioned is also throwing this discussion back. In the event of a return to it, the key issue will be the issue of security guarantees for individual states.

Eseniia Kosulina: In your opinion, what is the main lesson that regional states should learn from the current round of the Palestinian-Israeli conflict?

Vitaly Naumkin: To put it briefly: problems must be solved. The unresolved Palestinian problem, the neglect of it, first created the illusion of its secondary importance, and then the opportunity to neglect it by taking unilateral steps. The result was the tragedy of October 7. The response to the tragedy was further neglect and attempts at a unilateral solution. The result was a humanitarian tragedy in the Gaza Strip, actions close to genocidal practices, which will inevitably entail further radicalization. Another result was a decrease in support for Israel in the world, the growth of anti-Semitism and Islamophobia, and the political dead end into which Israel has driven itself.

Eseniia Kosulina: To what extent does the Russian approach to ensuring security in the Middle East correspond to the interests and needs of the countries in the region? In what areas is dialogue particularly effective today?

Vitaly Naumkin: Of course, it seems to me that it does. In essence, what is the quintessence of the Russian approach? That regional security should be comprehensive (that is, including all possible aspects of security), inclusive (that is, taking into account the interests of all regional players) and provided by the countries of the region themselves, because only this will be able to ensure their sovereignty and independence. Gradually, all three of these characteristics are finding increasing understanding among regional elites. Today, there is no longer such rejection of Iran as before, an increasing number of countries understand that neither the United States nor anyone else can ensure their security, and the very notion of security is becoming increasingly complex. Of course, there is the problem of small states for which reliance on external guarantees is both traditional and natural. However, in recent years, they have also seen an increasing desire for multi-vectorism, which could balance the unilateral American influence. It is enough to look at Qatar or the UAE in this regard.

Eseniia Kosulina: What role do you think science diplomacy plays in reducing tensions in the Middle East? Does it help opposing sides look at pressing issues from new angles?

Vitaly Naumkin: In essence, scientific diplomacy can only play a supporting role, strengthening classical diplomacy. In the Middle East, where international relations and foreign policy in general are often not very institutionalized, where wide networks of personal contacts traditionally play a huge role, traditional mediation mechanisms exist, and at the same time many conflicts are developing, a very broad field of activity for those engaged in scientific diplomacy.

Our institute – the Institute of Oriental Studies of the Russian Academy of Sciences – has always been quite active in this regard. We can recall the Dartmouth Conference, four rounds of inter-Palestinian consultations, three rounds of international expert meetings on security issues in the Gulf, the Valdai Club Middle East Dialogue, the “Russia – Middle East” Forum and our other regular events. In some cases they had a direct effect, in others – not, but even then, in my opinion, they played and continue to play an important role in creating dialogue formats, creating space for diplomacy.

Eseniia Kosulina: Not long ago the world crossed the “small equator of the century”: the year 2050 has become chronologically closer to us than the year 2000. In this regard, I ask you to briefly formulate what, in your opinion, should become the main priority in strengthening the global security system in the near future.

Vitaly Naumkin: This is preventing a nuclear catastrophe, strengthening food and environmental security, modernizing international institutions, and increasing their effectiveness.

[1] It is implied, first of all, Russia’s Collective Security Concept for the Gulf region – Editor’s note.