Before moving on to an analysis of trends in the NPT review process, it’s worth asking a simple question: is the NPT and its review process even necessary? What is its raison d’etre, especially in an era of stingy travel allowances, late visas, and rampant politicization? Is there a hidden meaning behind three inconclusive preparatory committees in a row, all incapable of producing recommendations for the inevitably fruitless NPT Review Conference?

There’s a temptation to give quick answers. Like, “we don’t need that kind of hockey”[1].

But it seems we still need hockey (meaning nonproliferation as a diplomatic sport) itself. Therefore, the real question is: how to play on changed ice? And what are the limits of what is possible at the NPT Review Conference, which will be held from April 28 to May 22, 2026, in New York?

Formalities: Why is a Review Process necessary?

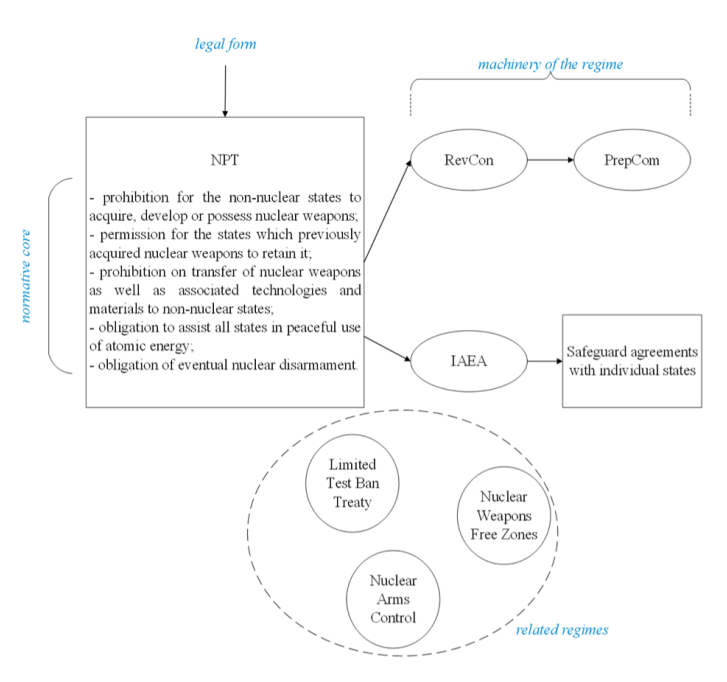

Let’s start by going back to the basics. Article 8 of the NPT provides for the convening of a conference of the parties to the Treaty “to review the operation of this Treaty with a view to ensuring that the objectives set forth in the Preamble and the provisions of the Treaty are being realized”. At the 1995 NPT Review and Extension Conference, it was decided to hold Review Conferences every five years.

Three preparatory committees are convened three years before the Review Conference, and if necessary, Preparatory Committee IV is held in the year of the Conference. The stated goal is to review the principles and objectives of the Treaty, as well as ways to achieve them, and to develop recommendations for the Review Conference. The conferences, in turn, are to evaluate the results of the review cycle and identify areas and methods for further progress[2].

…The fact that the NPT was granted indefinite status reflected the international community’s understanding of the need to preserve it as a universal instrument for ensuring international security and, at the same time, the agreement of States parties to undertake efforts to supplement the obligations contained in the Treaty with new measures for the practical implementation of its provisions. Further developments in subsequent review cycles have confirmed the validity and timeliness of the decision to extend the Treaty indefinitely. It has allowed States parties to more thoroughly address the strengthening of the Treaty regime, particularly with regard to the first two pillars – nuclear disarmament and nonproliferation. As a result, it was possible to agree on the so-called 13 steps of the 2000 Review Conference (RC), as well as the 2010 Action Plan adopted as a result of the successful conclusion of the next Review Conference.

Andrey Belousov

Deputy Permanent Representative of the Russian Mission to the UN Office and other International Organizations in Geneva

https://pircenter.org/en/editions/experts-on-the-npt-indefinite-extension-and-future-prospects-for-the-npt-2026-review-conference/

However, the organizational aspects of the Preparatory Committee’s work are not regulated in detail. The Final Document of the NPT Review Conference stipulates that the Third Preparatory Committee should submit consensus recommendations to the Review Conference. However, this has not been achieved since the decision to improve the effectiveness of the NPT review process was adopted, and a factual summary of the results of the work was only adopted in 2002[3].

It should be noted that the issue of improving the Review Process’s mechanics has been raised repeatedly at events within the NPT Review Process. The latest round of this discussion began after the 10th NPT Review Conference in 2022, which concluded without adopting a final document. Following its conclusion, and in advance of the first session of the Preparatory Committee, it was decided to convene a working group on enhancing the effectiveness of the Review Process[4].

It appears that the discussion that took place in 2023 reflects the sentiments of the States Parties to the Treaty regarding the specific parameters for reviewing its operation.

The following organizational and bureaucratic problems were noted: insufficient time for interactive discussions and duplication of ideas expressed within various PrepCom clusters, as well as a lack of a clear division of powers between the PrepCom and the RevCon. Specific considerations on this matter were presented by the United States[5]. Among the most unorthodox ideas was abandoning the structuring of the RevCon’s work into main committees. Instead, it is proposed to move directly to an article-by-article analysis of treaty implementation.

In addition, initiatives were put forward to create some kind of permanent operating body (from the NPT Secretariat to a support unit), to hold regional seminars and to appoint the Conference leadership in advance.

From the Russian side’s perspective, the potential benefits of streamlining the review process, however, do not outweigh the existing gaps and shortcomings. In particular, the added value of the European Union speaking independently is questionable. As noted in the Russian delegation’s statement, the European Union uses this platform to make unfounded accusations against member states and politicize the discussion. Furthermore, given the pressing need to save time, the rationale for a separate slot for non-governmental organizations to speak is unclear.

The most important thing, however, is that states’ full participation in the review process is not impeded. In this context, the practice of refusing to issue or delaying visas to experts from the Russian delegation cannot be described as anything other than outrageous. Despite some progress in this area compared to previous years, in 2025, visas were issued to two Russian experts only on the day of the event and after the personal intervention of the Chair[6].

…The NPT indefinite extension was a very important step that confirmed its uniqueness for international security. It eliminated the need to decide every five years whether to keep the treaty or not. It gave us confidence that there is no more proliferation of nuclear weapons in the world. Only specific issues inside and outside the NPT will need to be addressed. Since there are five states outside the Treaty, four of which are nuclear-weapon states, it is obvious that simple co-optation is not the answer. It is necessary to consider this issue on a case-by-case basis.

Alexey Arbatov

Academician of RAS Head of the Center for International Security at IMEMO RAS

https://pircenter.org/en/editions/experts-on-the-npt-indefinite-extension-and-future-prospects-for-the-npt-2026-review-conference/

The reporting dimension of the debate around improving NPT implementation deserves special mention. Non-nuclear-weapon states have raised the issue of the nuclear-weapon states’ national reports being subject to interactive review in terms of their implementation of Article VI of the Treaty. In fact, this idea became the core of the exchange of views within the relevant Working Group in 2023. As a compromise, the Philippines proposed the following wording, which would allocate a separate slot for reviewing national reports of states, and nuclear-weapon states in particular, in a manner that would allow for questions to be raised and clarifications to be provided regarding their content[7]. However, despite the absence of objections from the majority of working group participants, a consensus decision on this point was not reached.

In this case, we’re talking about form over substance. Non-nuclear-weapon states have the capacity to discuss the nuclear doctrines of nuclear-weapon states: there are bilateral consultation mechanisms and a format for sideline events. Detailed information on this matter is included in national reports submitted according to the format agreed upon by the nuclear-weapon states. Adding specially allocated time for their discussion – especially given the previously expressed concerns about time constraints – would add nothing to this. Sapienti sat[8].

At the same time, the authors of such initiatives, hoping that such discussions will increase transparency regarding existing nuclear arsenals, fail to take into account that the degree of such transparency is a purely national matter. The decision to publicize specific aspects of nuclear force activity must not undermine national security. In the context of the hybrid war unleashed against Russia, the added value of such transparency is, we repeat, unclear. At the same time, the Western “troika”, nodding at such approaches by the anti-nuclear vanguard, apparently hopes to disadvantage Russia and China by portraying them as opponents of nuclear disarmament.

Macro Trends of the Review Process

Two consecutive NPT Review Conferences (in 2015 and 2022) concluded without the adoption of a consensus final document. The third session of the Preparatory Committee for the 2026 NPT Review Conference also failed to produce agreed recommendations for the Treaty’s review. Thus, the Vietnamese Presidency of the Review Conference faces the virtually impossible task of finding common ground after failing to do so for over 16 years.

It would be incorrect to hurl slogans about the nuclear nonproliferation regime being on the brink of collapse. Nonproliferation still works. Since the last successful Review Conference (in terms of the adoption of a final document) in 2010, not a single new state has acquired nuclear weapons. IAEA safeguards continue to be implemented, the export control system functions, and reliable physical protection of nuclear facilities is generally ensured. Most importantly, Article IV of the Treaty, which provides for broad access for member states to the benefits of “atoms for peace”, is being implemented virtually without interruption.

It is also necessary to differentiate the reasons for the failures of the 2015 and 2022 Review Conferences. In the first case, the trigger was the unwillingness of the United States and Great Britain to join the consensus on the need to convene an international conference on the establishment of a Zone Free of Weapons of Mass Destruction and Their Means of Delivery in the Middle East[9]. In the second case, it was the Ukrainian issue, fueled by a hysterical Euro-Atlantic minority, and specifically issues related to the Zaporozhye Nuclear Power Plant[10]. These issues will be discussed further.

…The indefinite extension of the NPT in 1995 made Israel more reticent in opposing the creation of a Nuclear-Weapon-Free Zone in the Middle East. As a result of all this, Egypt has refused to ratify the CTBT. No NPT party wanted to end the Treaty, and the alternative, which was a 25-year revolving extension, would have been much more effective and useful because it would have put the Treaty and the parties under constant review working for Nuclear proliferation. The indefinite extension was a big mistake that was detrimental and testimony that the best can be the enemy of the good.

Nabil Fahmi

Foreign Minister of Egypt (2013-2014),

Dean Emeritus of the School of Global Affairs and Public Policy of the American University in Cairo

https://pircenter.org/en/editions/experts-on-the-npt-indefinite-extension-and-future-prospects-for-the-npt-2026-review-conference/

However, it should be noted that the absence of a final document is not a failure in itself. The key factor here is the fact that the Treaty’s validity was reviewed in any event. This provides food for thought.

But, of course, it is also true that the discussion materials must sooner or later lead to concrete actions to strengthen the nonproliferation regime in all its aspects and to achieve the noble goals enshrined in the Treaty’s preamble. At the present moment, the nuclear nonproliferation regime is plunging into a crisis, in essence rather than in form, calling into question its fundamental tenets. The lack of final documents at the 2015 and 2022 RevCons and the heated debates in the current review cycle are merely the result of the confluence of several alarming macro-trends.

Trend 1: Modus operandi between nuclear-armed states has slided toward conflict. The “P5” as a format is splintering into a Russian-Chinese tandem and a Western “troika”. In the absence of constructive interaction, the US, France, and the UK are attempting to shift responsibility for the dire state of strategic stability onto Russia and China. Anti-Russian and anti-Chinese rhetoric have become an integral part of every Western speech at Prepcoms[11].

Public squabbles are exacerbated by a reluctance to engage in concrete, substantive discussions behind closed doors. The issue isn’t a divergence of positions, but rather a reluctance on the part of Western capitals to make an effort to uphold the nonproliferation acquis communautaire[12], which is impossible without constructive dialogue.

Attempts to simply sideline the nuclear issue – to compartmentalize it, as the Biden administration has proposed – are not a solution in and of themselves. The current crisis in the multilateral architecture of international security is complex. Hypothetical agreements on individual issues, taken out of this context, will not resolve the overall negative trend of deepening interstate tensions. The most that can be achieved in this scenario is a fine-grained gesture under Article VI of the NPT, which does not imply any real progress.

Trend 2: Growing rejection of nuclear deterrence concept and practices by non-nuclear states. The Treaty on the Prohibition of Nuclear Weapons has gained a critical mass of supporters and allows anti-nuclear radicals to further their narrative about the humanitarian consequences of nuclear weapons and the unacceptability of nuclear deterrence as a concept. As a result, relevant international forums are becoming saturated with a large number of initiatives that divert the discussion and fail to take into account the interests of states with strategic capabilities.

It must be acknowledged that, from the perspective of Russian interests, anti-nuclear radicals can be useful companions in their criticism of Western approaches to the NPT (for example, regarding NATO’s joint nuclear missions). At the same time, the narrative they generate about the NPT’s crisis, the failure of nuclear states to fulfill their disarmament obligations, and the creation of an “in-house” alternative in the form of the TPNW undermine faith in the nonproliferation regime and its intrinsic value.

Meanwhile, the proposed introduction of some kind of expanded reporting obligations as part of the review process misses the mark. Their added value is far from clear, as they address not the root causes of the international security crisis, but rather attempts to “concoct” some bureaucratic formula to simulate vigorous activity.

Trend 3: Attempts to use nonproliferation as a pretext for pursuing narrow, selfish political ambitions. It would be wrong to describe this as a new phenomenon – after all, the example of Iraq in 2003 remains resonant. The US-Israeli attacks on Iranian nuclear facilities only confirm the urgency of this problem.

It must be clearly and unambiguously stated that operations such as this, in the absence of a genuine international legal basis, pay nonproliferation a bad service. The main conclusion for threshold states is that the implementation of a weapons scenario cannot be delayed, as the opponent will seek a preemptive strike. This, at a minimum, risks the creation of a large number of nuclear and conventional umbrellas in the most security-sensitive regions – the cooperation between Saudi Arabia and Pakistan is a case in point.

Trend 4: In connection with the Iranian case, it is important to note that the countries of the collective West have embarked on a course of fragmentation of the “global nuclear family”, isolating their own space from fair competition in the peaceful use of nuclear energy. This includes both a series of “petty nastinesses”, such as the denial of visas for Prepcom-2025 to employees of China’s CNNC and the delays in issuing them to specialists from the Rosatom State Corporation, and even more serious indecencies. These include sanctions that impede the implementation of current and prospective nuclear projects in third countries (a classic example is the blocking of funds for the construction of the Akkuyu NPP in Türkiye). These include unfair attempts to sabotage the Paks-2 NPP project (Hungary) through administrative means. These include attempts to impose their own regulatory requirements and decisions regarding nuclear fuel at any cost, simply to squeeze Russian suppliers out of the nuclear fuel market for European NPPs. The list goes on – incidentally, this includes the Iranian example mentioned in the previous point.

However, the consequence of such steps is not the creation of a “flourishing atomic garden”, but the undermining of the letter and spirit of Article 4 of the NPT, which presupposes the fullest possible international cooperation in the field of peaceful nuclear energy.

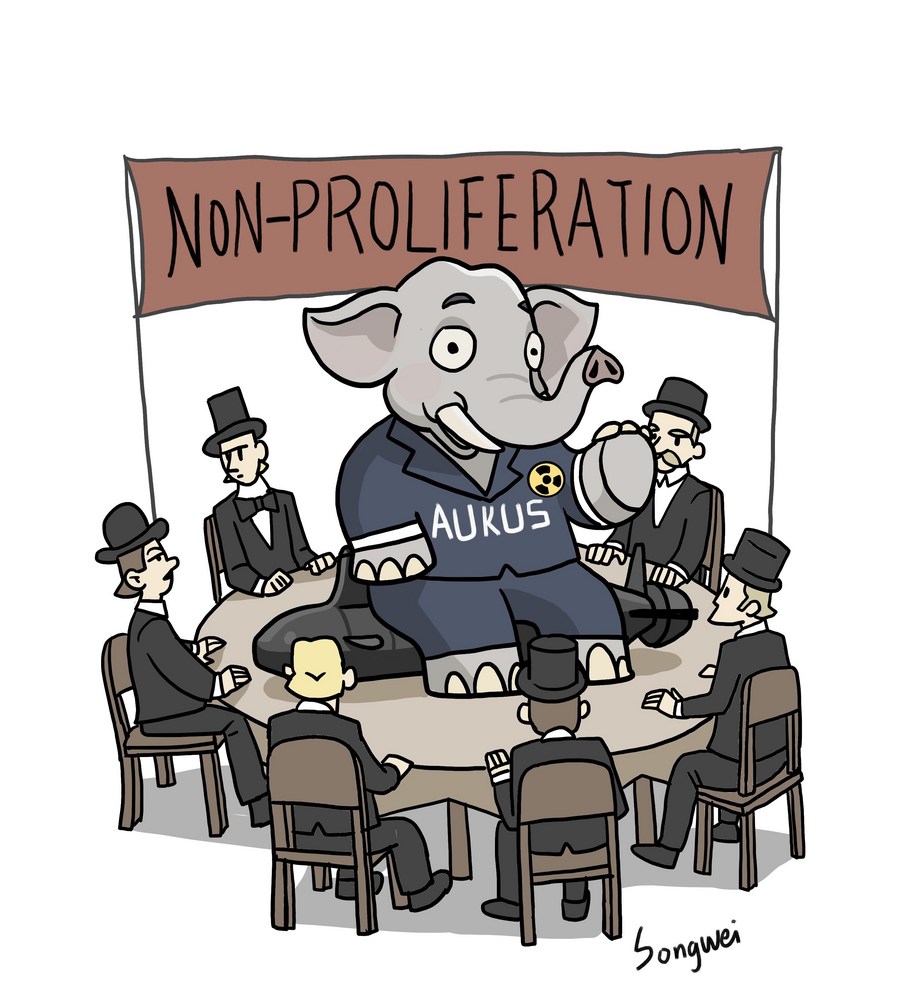

Finally, Trend 5 is the emergence of a third category of states that cannot acquire nuclear weapons, but can touch them. This issue was highlighted at the 2025 PrepCom. Essentially, certain Western countries have been placed in a category of those that are allowed leniency and even exceptions in the area of nonproliferation due to their unblemished reputation.

An example is the continuation and expansion of NATO’s practice of joint nuclear missions and the options being considered for replicating them in the Asia-Pacific region. The involvement of non-nuclear states, including new NATO members, in supporting such nuclear combat missions and practicing them during exercises.

Scenarios warned about by Russian experts are also coming to fruition. Specifically, South Korea has announced plans to build its own nuclear submarine in the AUKUS space. And there’s little doubt that it will also be declared an exception to the rule.

Finally, the most egregious example is Ukraine, which effectively gets away with attacks on nuclear power plants despite the presence of IAEA specialists there. Essentially, this is a deliberate disregard for the prospect of a man-made nuclear catastrophe provoked by the Nazi regime in Kiev.

The 2026 Review Conference: Major Challenges

From the above, it is clear that the 11th NPT Review Conference will be held in a combat-like environment. And these battles are of global significance. Let us highlight the issues that could provoke the most intense clashes.

In the disarmament cluster:

The expiration of the New START Treaty on February 5, 2026, will cause a vacuum in arms control and create an extremely unfavorable backdrop for discussions on nuclear disarmament. The initiative put forward by Russian President Vladimir Putin to unilaterally maintain the New START ceilings for another year will help mitigate some of the negative impact. Much will depend on the US position going forward, both on this initiative specifically and in the context of the review of the Nuclear Posture Review, the fundamental document of American nuclear policy.

The most desirable development would be the launch of bilateral consultations on strategic stability. This would at least signal to the global majority that nuclear-weapon states take their Article VI obligations seriously. This latter possibility, however, is wishful thinking. This is evidenced, in particular, by the US’s commitment to resuming nuclear testing.

Accordingly, a far more likely scenario is a repeat of the unsavory pattern of previous NPT Review Conferences and Preparatory Committees, with mutual accusations across the entire strategic dossier. Fortunately, there are plenty of grounds for this: US plans to deploy the “Golden Dome”, the deployment of American medium-range missiles in the Philippines, Japan, and Germany, and preparations for the reintroduction of sea-launched cruise missiles with nuclear warheads. The Americans will attempt to blame our country for alleged violations of the New START and INF Treaty, its arsenal of non-strategic nuclear weapons, the testing of the new Burevestnik and Poseidon deterrent systems, and the alleged departure from the “zero standard” of nuclear testing.

There’s enough heresy, where there’s a will.

The progress of the 2023-2025 PrepComs suggests that Western countries’ criticism of the People’s Republic of China’s nuclear modernization will be further developed. It’s noteworthy, however, that at recent meetings, it wasn’t even the United States that particularly emphasized this issue, but its Western and Eastern European satellites. Given the keen interest of Western publications in the products displayed at the PLA parade marking the 80th anniversary of victory in World War II, it seems entirely likely that the collective West’s insinuating statements will include references to this event.

It must be emphasized that our Chinese comrades do not leave such attacks unanswered. This is especially true given that Washington regularly exposes itself to counter-criticism, provoking an arms race in the Asia-Pacific region by increasing its presence in that part of the world, deploying destabilizing military capabilities there (for example, the aforementioned intermediate- and shorter-range missiles), and developing nuclear alliances with regional partners (see, for example, the Washington Declaration with the Republic of Korea).

It’s possible that “irresponsible nuclear rhetoric” will resurface again – from the West, in relation to the Russian Armed Forces’ Special Military Operation (SMO) in Ukraine. The ridiculousness of such statements requires no comment. What’s important is that NATO’s dandruff has begun to allow for provocative remarks – just recall the Belgian Defense Minister’s threat to “wipe Moscow off the face of the earth”. This illustrates the pernicious and sinister role the Alliance plays in nonproliferation.

Thus, unity within the nuclear five is a scenario that is as desirable as it is unrealistic. Britain and France would form an alliance with the United States, which would create objective preconditions for a closer Russian-Chinese tandem.

Regarding multilateral nuclear disarmament – the object of desire for the anti-nuclear vanguard – the discussion will likely revolve around two positions. The most acute and focused is the idea of ensuring greater transparency in the implementation of obligations by nuclear-weapon states under Article VI of the Treaty. The lowest common denominator on this issue is the idea of a structured interactive discussion of the national reports of nuclear-weapon states – an idea, as emphasized above, that is not without controversy. In this context, at a minimum, the national reports of those states participating in NATO joint nuclear missions or covered by so-called “extended deterrence commitments” from their nuclear sponsors should be analyzed just as closely.

In the nonproliferation cluster:

Even at the time of previous Review Conferences, this area was plagued by significant controversies. Among the most important topics were the functioning of the so-called “nuclear alliances”, the Iranian and North Korean dossiers, the functioning of the IAEA safeguards system, the Comprehensive Nuclear-Test-Ban Treaty, and the creation of a WMD-free zone in the Middle East.

The most long-term consequences for the nuclear nonproliferation regime undoubtedly stem from the unprovoked aggression of Israel and the United States against the Islamic Republic of Iran, which involved attacks on nuclear facilities under IAEA safeguards. The basic, indisputable fact is that what happened was a flagrant violation of the fundamental norms of international law. But most importantly, the actions of Washington and West Jerusalem demonstrated that there can be no middle ground on the issue of nuclear weapons possession, and that in the face of an acute geopolitical threat, the pursuit of a nuclear arsenal must be accelerated – for only strategic deterrence, i.e., nuclear deterrence, can prevent such attacks.

The launch by the United States, France, Germany and the United Kingdom of the process of reimposing all UN sanctions against Iran, lifted by Security Council Resolution 2231, is also having a corrosive effect on all nonproliferation diplomacy. Its immediate consequence is the further balkanization of the international legal system, dividing it into de jure and “the law of the strongest and most arrogant”. In the long term, this reduces any incentives for potential nuclear weapons possessors to reach agreements.

In this context, the North Korean nuclear dossier, from Russia’s perspective, becomes purely a matter of pious wishes for the universalization of the Treaty. UN sanctions imposed against North Korea have lost all relevance. In this light, the Russian Federation’s decision to block the work of the 1718 Committee appears unequivocally correct and logical – especially since it has become a pliable tool in the hands of those who wish to impede legitimate trade, economic, and humanitarian cooperation between Russia and North Korea. A completely logical step would be to officially recognize that North Korea has completed its withdrawal from the NPT and is no longer bound by its relevant obligations.

Regarding the Middle East’s WMD-free zone, it should be noted that despite four UN-sponsored conferences on this issue, Arab states show no intention of easing the debate on this topic. Moreover, the genocide in Gaza Strip and the threat of using nuclear weapons against Palestinians are justifiably irritating states in the region. Even during the period of actual freezing of the conflict. Consequently, the potential for failure to hold a conference on this topic has not been exhausted.

An important point: a number of states are noticing “the smell of nuclear proliferation” in the air. It’s advisable to bring them into the spotlight, as this poses a real threat to undermining the Treaty. Let those who speak of such scenarios be devoured by the TPNW radicals.

In the “peaceful atom” cluster:

It’s clear that without a resolution to the Ukrainian crisis, the Zaporozhye Nuclear Power Plant and everything related to Ukraine will remain on the agenda. Overall, the discussion around this country, while not fading into the background, is losing its urgency. As already noted, the key is ensuring the security of the Zaporozhye NPP, a Russian nuclear facility that is subject to daily attacks by the Ukrainian Armed Forces. The inadmissibility of such attacks must be clearly stated in any final document. This is a sine qua non[13].

Regarding other issues related to Ukraine, one thing is certain: the less the stench of death, the better. Any verbal provocations on this matter will be met with a factually accurate retort. And if Western governments feel like walking out of the meeting room in shame at this point, so much the better. Russia will not mince words, especially since, as Ukrainian Nazism retreats from Russia’s regions, additional evidence of their atrocities is uncovered.

Conclusion

In light of the above, it’s time to return to the question: “Do we need this kind of hockey?” And how should we “play the match” at the upcoming NPT Review Conference? Should we rely on “assists” with friendly powers or on outscoring opponents? Feint or go all-out?

…The decision to extend the Treaty reaffirmed the importance of its three pillars: nonproliferation, disarmament, and peaceful use of nuclear energy under IAEA safeguards.

Li Sikui

Professor at the Institute of Regional and Country Studies

University of International Business and Economics (Beijing, China)

https://pircenter.org/en/editions/experts-on-the-npt-indefinite-extension-and-future-prospects-for-the-npt-2026-review-conference/

The answer is simple and obvious: act within the original, fundamental logic of Article 8 of the NPT – review the operation of this Treaty to ensure that the objectives set out in the Preamble and the provisions of the Treaty are being realized. Its usefulness lies in its role as a mechanism for synchronizing watches and capturing the views of the global majority. Its purpose is not to provide a paper-based nonproliferation document, but rather to confirm that the Treaty is needed and is being implemented – even if only at the lowest common denominator. This, in turn, will allow us, albeit informally, to determine the agenda for further measures to strengthen this regime.

[1] The phrase is a quote from the famous Soviet sports commentator Nikolay Ozerov, who first used it in the 1960s. It refers to hockey played with excessive brutality or unsportsmanlike conduct, expressing a desire for a more skilled and fair game rather than a dirty one – Editor’s note.

[2] Decisions and resolution adopted at the 1995 NPT Review and Extension Conference // NTI, 1995. URL: https://media.nti.org/pdfs/npt95rc.pdf

[3] Potter W. Behind the Scenes: How Not to Negotiate an Enhanced NPT Review Process // Arms Control Association, 2023. URL: https://www.armscontrol.org/act/2023-10/features/behind-scenes-how-not-negotiate-enhanced-npt-review-process#endnote03

[4] NPT/CONF.2020/DEC.2 // United Nations, 2020. URL: https://docs.un.org/en/NPT/CONF.2020/DEC.2

[5] Working Group on Strengthening the NPT Review Process U.S. Working Paper Practical Steps to Improve the Process and Reinforce Best Practices // Reaching Critical Will. July 24-28, 2023. URL: https://reachingcriticalwill.org/images/documents/Disarmament-fora/npt/prepcom23/wg/WG-WP-USA.pdf

[6] See e.g.:Statement by the Deputy Head of the Delegation of the Russian Federation at the Third Session of the Preparatory Committee for the Eleventh Review Conference of the Treaty on the Non-Proliferation of Nuclear Weapons (Improving the Review Process), New York, May 7, 2025 // MFA of the Russian Federation. May 7, 2025. URL: https://mid.ru/ru/foreign_policy/international_safety/2014659/ (in Russ.).

[7] Potter W. Behind the Scenes: How Not to Negotiate an Enhanced NPT Review Process // Arms Control Association, 2023. URL: https://www.armscontrol.org/act/2023-10/features/behind-scenes-how-not-negotiate-enhanced-npt-review-process#endnote03

[8] Sapienti sat – a Latin expression meaning “it’s enough for the wise” or “it’s enough for the understanding.” It implies that a wise person will understand the meaning of what is said without lengthy explanations, while for the understanding person, a hint or a brief allusion will suffice – Editor’s note.

[9] See e.g.: Orlov V. The Glass Menagerie of Nonproliferation: Why the Review Conference Failed // Russia in Global Affairs Journal. August 24, 2015. URL: https://globalaffairs.ru/articles/steklyannyj-zverinecz-nerasprostraneniya/ (in Russ.); Potter W. Unfulfilled Promise of 2015 NPT Review Conference // VCDNP, 2020. URL: https://course.vcdnp.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/04/00396338.2016.1142144.pdf

[10] Selezneva D. Problems and Prospects of the Treaty on the Non-Proliferation of Nuclear Weapons // Analysis and Forecast. IMEMO RAS Journal, 2022. URL: https://www.afjournal.ru/2022/4/global-and-regional-security/treaty-on-the-non-proliferation-of-nuclear-weapons-problems-and-prospects (in Russ.).

[11] See e.g.: NPT News in Review. Vol.20, №2 // Reaching Critical Will. May 1, 2025. URL: https://reachingcriticalwill.org/images/documents/Disarmament-fora/npt/NIR2025/NIR20.2.pdf

[12] Acquis Communautaire (often acquis) – is the body of laws, legal acts, and court decisions that has formed the basis of European Union law since 1993. In the text it is used in a figurative, metaphorical sense. – Editor’s note.

[13] Sine qua non – a Latin expression that translates as “without which it is impossible” and refers to a necessary or indispensable condition. It can be an essential element, component, or requirement without which something cannot exist or be realized – Editor’s note.