The modern information space is becoming increasingly integrated and simultaneously vulnerable to various types of cyber threats, which can significantly impact the national security of states. Russia, as one of the world’s leading powers, has developed a comprehensive strategy to ensure international information security, taking into account both national interests and the need to form joint international mechanisms. Russian scientists and experts in the field of international information security consider information as a “gold and foreign currency reserve” and a strategic resource for ensuring stability and sovereignty in the national information space[1]. At the same time, information and its use through modern information and communication technologies (ICT) are also regarded as an effective offensive and defensive potential of the state.

To better understand Russia’s national interests in this sphere and how they developed over time, it is worth paying attention to a number of doctrinal documents adopted in recent years, the newest of which is the Foreign Policy Concept of the Russian Federation, adopted in 2023[2].

The development of a safe information space and the protection of Russian society from destructive foreign informational and psychological influence are listed as the fifth of nine points in the section “national interests of the Russian Federation in the foreign policy sphere”. The Concept particularly emphasizes that in case of “hostile actions by foreign states or their associations representing a threat to the sovereignty and territorial integrity” of Russia, including (…) “using modern information and communication technologies”, its authorities reserve the right to “take symmetrical and asymmetrical measures necessary to stop such hostile actions, as well as to prevent their recurrence in the future”.

The most important tasks of Russia in ensuring international information security, countering threats to it, and strengthening Russian sovereignty in the global information space are listed in a separate section. If grouped, three spheres of interest can be distinguished.

First, this is “strengthening and improving the international legal regime for preventing and resolving interstate conflicts and regulating activities in the global information space”, as well as “taking political-diplomatic and other measures aimed at countering the policies of unfriendly states regarding the militarization of the global information space, the use of information and communication technologies for interference in the internal affairs of states and military purposes, as well as limiting access of other states to advanced information and communication technologies and increasing their technological dependence”.

Second, it is “forming and improving the international legal foundations for countering the use of information and communication technologies for criminal purposes”.

Third, “ensuring the safe and stable functioning and development of the Internet telecommunications network based on equal participation of states in managing this network and preventing foreign control over its national segments.”

These tasks are listed in more detail in the Presidential Decree of the Russian Federation dated April 12, 2021, No. 213, which approved the updated Fundamentals of State Policy of the Russian Federation in the field of international information security[3]. Among other things, this document also provides the Russian understanding of international information security: “It is such a state of the global information space in which, based on generally recognized principles and norms of international law and on the basis of equal partnership, international peace, security, and stability are maintained”[4].

Russia’s national interests in international information security are multilayered by nature. Many sub-tasks can be distinguished within each of the three areas of work listed above, and the directions largely overlap. To better understand what exactly Russia strives to achieve in each of the specified areas, it is worth delving a little into the history of Russian diplomacy.

Moral Code

For almost 30 years, Russia has been the initiator of key diplomatic mechanisms and processes in the field of international information security. It was at Russia’s initiative that the first dedicated resolution “Achievements in the field of informatization and telecommunications in the context of international security” was adopted on December 4, 1998[5]. According to Sergey Boyko, an expert of the Russian Security Council apparatus, this resolution opened the era of Russian initiatives in the field of international information security at United Nations[6].

A little-known detail (noted in his article by Sergey Boyko) is that before the adoption of this resolution, then Russian Foreign Minister Igor Ivanov sent a letter to then UN Secretary-General Kofi Annan warning of the threats that could arise from the emerging widespread use of information and communication technologies[7]. The Russian authorities had already foreseen the risks of an arms race, interstate conflicts, and other problems in this area and considered it important to bring this issue to the discussion at the UN.

Therefore, the Russian-proposed resolution spoke of the “expediency of developing international legal regimes to ensure the security of global information and telecommunication systems and combat information terrorism and crime”. However, this wording caused objections from a number of countries (mainly Western, including the USA), and it was softened to “international principles” instead of “international legal regimes”, which allowed the resolution to be adopted by consensus. According to Sergey Boyko, thanks to this Russian initiative, current issues of security in the use of ICT and ICT themselves have firmly entered the agenda of the First Committee of the UN General Assembly[8].

Russia devoted the following decades to working on the tasks proposed in the resolution. However, the contradiction between its desire to develop legally binding rules and the reluctance of some states to accept such restrictions, preferring instead soft law, has remained (and remains) one of the key contentious issues. This issue provoked some of the most heated discussions within the Group of Governmental Experts on Developments in the Field of Information and Telecommunications in the Context of International Security (GGE) – a mechanism created in 2004 also at Russia’s initiative on the UN platform to discuss international information security issues.

In 2010, 2013, and 2015, this group, initially composed of 15, then 20, and later 25 states, presented a series of important reports containing the first lists of principles for responsible state behavior in the information space. A particularly significant report was issued in 2015. It recommended that states cooperate in preventing the malicious use of ICT and avoid knowingly allowing their territory to be used for internationally wrongful acts involving ICT. It called for enhancing information exchange and mutual assistance aimed at pursuing terrorists and preventing criminal uses of ICT. The group underscored that states must ensure comprehensive respect for human rights, including the rights to privacy and freedom of expression.

Another important recommendation is that states should not carry out or knowingly support ICT activities intended to cause deliberate harm to critical infrastructure or create other obstacles in its use or operation. In addition, states must take appropriate measures to protect their own critical infrastructure from ICT threats. States should not harm the information systems of other states’ Computer Emergency Response Teams (CERTs) or use such teams for malicious international activities. States should maintain responsible disclosure about ICT vulnerabilities, adopt reasonable measures to protect the integrity of supply chains, and prevent the spread of malicious ICT software, technical means, or harmful hidden functions (so-called “backdoors”)[9].

The Russian Foreign Ministry, commenting on the group’s results, called the final report “an important politico-legal document laying down the general framework for state interaction in the information space”[10]. The ministry’s statement emphasized that international law applies to the use of ICT, but where necessary, it can be developed further, including through the adoption of new principles and norms. This last part was especially important to Russia, which continued to seek legally binding rules. The norms outlined in the GGE report, however, remained voluntary, with no sanctions for non-compliance.

…The final report builds on the key provisions of the 2010 and 2013 GGE reports and develops them in line with contemporary realities. A new element of it is the requirement that any accusations against states of organizing and committing illegal acts using ICTs must be proven. This precludes the possibility of “indiscriminate” prosecution of states for attacks allegedly committed in the information space.

The report recognizes that international law is applicable to the use of ICTs; however, if necessary, it can be developed, including through the adoption of new principles and norms. In this context, special attention is paid to the development of norms, rules, and principles for responsible state behavior in the ICT space. <…> Discussions on international information security (IIS) issues at the key international forum – the UN – are maintained. The recommendatory section of the report suggests that regular institutional dialogue on IIS should continue within this organization.

MFA of the Russian Federation

June 30, 2015

https://www.mid.ru/ru/foreign_policy/un/1511194/

The GGE worked intermittently until 2021. In parallel, from 2019, another UN mechanism initiated by Russia was launched – the Open-ended Working Group (OEWG) on security in the use of ICT. Like the GGE, the OEWG aimed to develop rules of responsible state behavior in the information space but was more inclusive and democratic. Almost all UN member states participated, along with intergovernmental and non-governmental organizations and business delegations.

The OEWG built upon the voluntary norms established earlier by the GGE but further clarified and developed them. These norms remained voluntary, although, at Russia’s insistence, the OEWG documents repeatedly stressed that states might need legally binding rules in the future.

Russia also succeeded in realizing a practical proposal – the creation of a “Global Directory of Points of Contact” to facilitate communication among national computer incident response teams (CERTs) of different countries (in Russia, this is the National Coordination Center for Computer Incidents, created by the FSB) and generally facilitate bilateral and multilateral information exchange[11]. This directory, launched in 2024 (available on the UN Office for Disarmament Affairs website, UNODA[12]), became the first universal confidence-building measure implemented within the OEWG.

The OEWG, initiated in 2019, experienced several compositions and completed its work in mid-2025. It was decided to replace it with a permanent mechanism – a decision supported and promoted by Russian authorities. According to statements by Russian Foreign Ministry representatives, Moscow still hopes that work in this area (the first of the three outlined in the Foreign Policy Concept) will ultimately lead to the development of comprehensive international legal instruments focusing on the prevention and resolution of interstate conflicts[13].

A Convention Concept

Russia has also submitted the draft of such a full-fledged international legal instrument – not once but three times. It refers to the UN Convention on Ensuring International Information Security. The first concept was presented by Russian authorities in 2011, the second in 2021, and the third in 2023. The latest document was co-submitted by Russia with Belarus, North Korea, Nicaragua, and Syria as an official document of the 77th session of the UN General Assembly[14].

The Russian Foreign Ministry expressed confidence that the international discussion on international information security reflects “growing support among UN member states for the idea of adopting a universal legally binding instrument that would ensure stability and security in the global information space”[15]. The initiative jointly presented by Russia and its like-minded states is considered in Moscow as a prototype of such an international treaty.

For the understanding of Russian interests in international information security this document is extremely important because it clearly reflects what Russia ideally aims to achieve in this sphere. It builds upon the works of the GGE and OEWG but specifically reflects the Russian vision of how international information security should be ensured.

Two principles run as a red thread throughout the document: the principles of sovereign equality of states and non-interference in their internal affairs.

Based on these principles, Russian authorities propose the following critically important provisions in the Convention concept from Russia’s perspective[16]:

- Sovereign rights of every state to ensure the security of its national information space, establishing norms and mechanisms for managing its information and cultural space in accordance with national legislation;

- Sovereign equality and equal rights and obligations of states regardless of economic, social, political, or other differences within the international information security system;

- Refraining from threats or use of force against the ICT infrastructure of other states or as a means of conflict resolution;

- Prohibiting the use of ICT to undermine or encroach upon sovereignty, violate territorial integrity and independence of states;

- Refusal to use ICT to interfere in the internal affairs of sovereign states;

- Impermissibility of baseless accusations against other states regarding organizing and committing ICT offenses, including cyberattacks, especially when used to justify unilateral economic sanctions and other measures;

- Resolving interstate conflicts through negotiation, mediation, reconciliation, or other peaceful means of their choice, including consultations involving national bodies responsible for detecting, preventing, mitigating the consequences of cyberattacks, and responding to cyber incidents.

This is not an exhaustive list of provisions that the Russian side would like to see in a legally binding Convention on international information security, but these points clearly demonstrate the basis of the Russian position.

The Convention draft also includes a section “Main threats to international information security and influencing factors”, which clearly shows what Russia does not want to see in this area[17]. Among such actions are:

- Using ICT by states in military-political and other spheres to undermine (encroach upon) sovereignty, violate territorial integrity, social and economic stability of sovereign states, interfere in their internal affairs, and perform other actions in the global information space impeding the maintenance of international peace and security;

- Conducting cyberattacks against states’ information resources, including critical information infrastructure;

- Monopoly by individual states and/or their supported private companies over the ICT market by limiting access of other states to advanced ICT and increasing their technological dependence on dominant informatization states, increasing digital inequality;

- Unfounded accusations by some states against others in organizing or committing ICT offenses, including cyberattacks;

- Using information resources under the jurisdiction of another state without coordination with that state’s competent authorities;

- Including undeclared capabilities in ICT and concealing vulnerabilities in products by manufacturers;

- Disseminating information through ICT that harms the political, social, economic, spiritual, moral, and cultural foundations of states, as well as threatening life and safety of citizens.

By submitting the Convention draft for consideration by UN member states, Russia, as noted by the Foreign Ministry, aimed to prevent and resolve conflicts, establish interstate cooperation, including strengthening the capacity of developing countries in the sphere of information security. The Ministry emphasized that Russia and co-authors are open to further discussion, taking possible proposals and comments into account, and called on foreign partners to join the initiative “in the interests of building a fair and comprehensive international information security system.”[18].

So far, however, a substantive discussion on this document has not started yet. The discourse within the framework of the GGE, and then the OEWG, gradually moved towards the idea of legally binding rules, but slowly, and constantly encountering opposition from skeptics. In addition, the chances of the Russian initiative on international information security to pass were negatively affected by the between Russia and the West confrontation around Ukraine. However, Moscow remains focused on results and refers to the success of Russian diplomacy in the second area – the formation of an international legal framework to counter the use of information and communication technologies for criminal purposes[19].

First Universal Treaty

In December 2024, the UN General Assembly approved the Convention against Cybercrime – the first universal international treaty on international information security. Russia was also the initiator of its development. Since 2017, Russia promoted at the UN an alternative to the Budapest Convention of the Council of Europe on Cybercrime. The Budapest Convention, signed in 2001, had been the most significant intergovernmental mechanism to combat cybercrime, ratified by 68 countries (mostly Western)[20].

However, Russian authorities initially regarded the Budapest Convention as a tool for interference in the internal affairs of other states and a violation of their sovereignty. Moscow was particularly dissatisfied with Article 32 of the Budapest Convention on cross-border access to stored computer data, which Russian authorities interpreted as allowing various intelligence services to conduct operations inside third countries’ computer networks without official notification. Russian authorities believed granting foreigners such access would threaten Russia’s security and sovereignty.

In 2019, Russia succeeded in getting the UN General Assembly to adopt Resolution 74/247 establishing a Special Committee “to develop a comprehensive international convention on countering the use of ICT for criminal purposes”[21]. Most Western countries opposed this; they aimed not to draft a new document but to expand the scope of the Budapest Convention. However, Western states eventually revised their position and actively joined the Special Committee’s work, which involved experts from over 160 countries and 200 non-governmental organizations.

Russia submitted its own draft versions of the Convention to the UN twice – in 2017 and 2021. The preparation involved the Prosecutor General’s Office, Ministry of Interior, Foreign Ministry, and other Russian agencies. Moscow insisted that the Convention cover the broadest possible range of criminal acts in the information sphere, emphasizing the UN General Assembly Resolution 74/247’s task of developing a “comprehensive Convention”. Russia’s 2021 draft proposed criminalizing 23 types of offenses. Western countries, conversely, sought to narrow the scope of the new legal instrument, which Russia saw as an attempt to “dilute and undermine the new agreement”[22].

The negotiations were extremely difficult. Many Russian proposals were included in the final text, but not all. Notably, provisions criminalizing the use of cyber technology for incitement to subversive activities, extremism, and terrorism were excluded. Western negotiators, including NGOs, argued that there was no universally accepted definition of these terms and feared that including such articles could enable authoritarian governments to crack down on dissent online[23].

Some other provisions insisted on by Western states, mainly related to human rights, drew criticism from Russia[24].

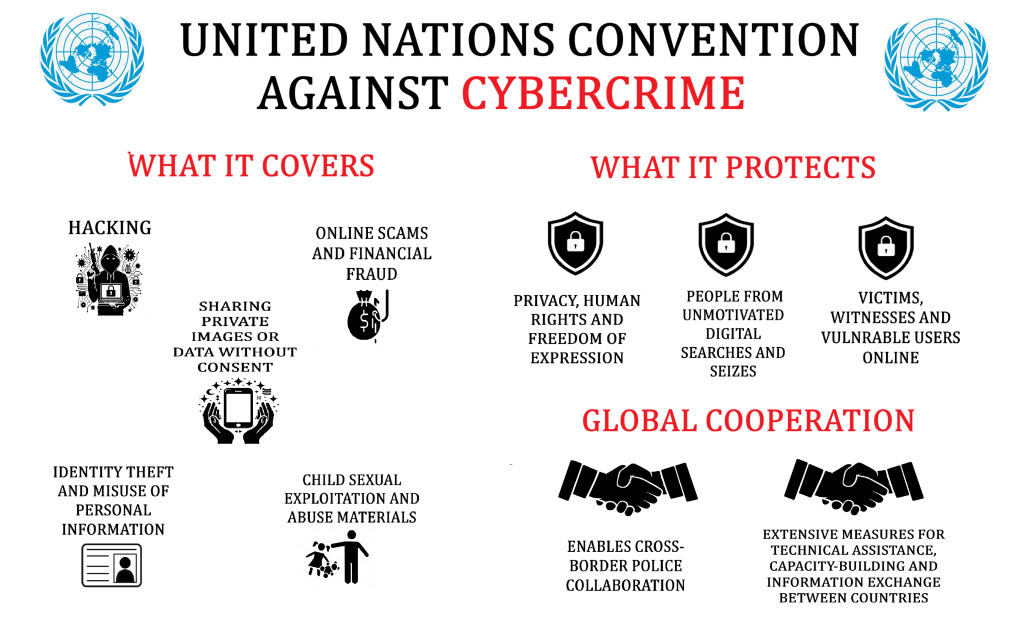

Despite the tense negotiations, the participants managed to reach a compromise, and the draft Convention was approved – first by the Special Committee, then by the Third Committee of the UN General Assembly, and finally, in December 2024, by the full General Assembly. The document received a complex title reflecting the compromises: “United Nations Convention against Cybercrime; enhancing international cooperation in combating certain crimes committed through information and communication systems, and in the exchange of electronic evidence relating to serious crimes.” Its opening for signature was planned for October 2025 in Hanoi, Vietnam. The Convention will enter into force after at least 40 countries ratify it.

The document covers ten categories of crimes, including unauthorized access to information and communication systems, illegal interception of data, interference with electronic data and systems, misuse of devices, forgery, theft or fraud using ICT, child pornography, and non-consensual dissemination of intimate images[25].

Although not all of Russia’s proposals were accepted, Russian authorities welcomed the adoption of the Convention. The Russian Foreign Ministry expressed hope that it would become “a solid foundation for establishing law enforcement cooperation to combat the use of information and communication technologies for criminal purposes”[26]. Regarding offenses not included in the new treaty, the Ministry indicated Russia’s expectation that the convention’s scope could be extended in the future through protocols covering additional crimes, focusing on combating the use of ICT for terrorism and extremism, as well as drug and arms trafficking.

Internet Governance

Regarding Russia’s interests in the third area mentioned in the Foreign Policy Concept of the Russian Federation – ensuring safe and stable functioning of the Internet based on the equal participation of states in its governance and preventing the establishment of foreign control over its national segments – the key element of Russian strategy is supporting the internationalization of Internet governance and enhancing the role of states in this process.

Russia advocates for reforming the global model of Internet governance, which is currently largely dominated by the international organization The Internet Corporation for Assigned Names and Numbers (ICANN, headquartered in Los Angeles, USA) and multilateral multi-stakeholder structures. The role of states in this ecosystem is limited. The Russian authorities believe that the current model does not provide sufficient security and protection of users’ rights and propose strengthening the role of states as guarantors of rights, the economy, security, and stability of Internet infrastructure[27]. Leading Russian academic experts and practitioners in the field mostly share this view[28].

Within the UN system, Russia insists on adopting a range of coordinated measures, such as increasing the role of states in the Internet governance process, developing a global policy on Internet governance at the interstate level, ensuring its stable and secure functioning based on international law, and preserving the sovereign right of states to regulate their national segments of the Internet. Russia would like to endow a specialized UN structure – the International Telecommunication Union (ITU) – with these functions and powers[29]. According to Russian authorities, the ITU has the necessary competencies and is widely involved in developing various Internet standards and protocols. The ITU includes companies, international and regional organizations, and scientific institutions, but states play the key role, which explains Russia’s choice of it as a possible international platform for developing legal norms and standards in Internet governance.

In 2021, the Russian communications administration nominated Rashid Ismailov (President of PJSC VimpelCom, 2014–2018 Deputy Minister of Communications and Mass Media of the Russian Federation) as a candidate for ITU Secretary-General. Among the priorities of his program were support for a human-centered digital economy and society; bridging the gap in access to information and communication technologies and developing human potential in third-world countries; managing risks, problems, and opportunities arising from the rapid development of communications technologies; creating an antimonopoly environment for innovation in telecommunications and information technology; strengthening cooperation among ITU members[30].

However, at the ITU Plenipotentiary Conference elections in 2022, the American Dorin Bogdan-Martin won. According to official results, out of 164 valid votes, Dorin Bogdan-Martin received 139, and Rashid Ismailov received 25[31]. Afterward, Russian authorities emphasized that Russia is ready to continue working with the ITU and is open to cooperating with the new Secretary-General[32].

An Outlook

It can be expected that Russia will continue to develop and adapt its international information security policy in the future, considering dynamic technological changes and increasing geopolitical complexity. A crucial task will be balancing national interests and the demands of global and regional cooperation (primarily within integration structures such as BRICS, SCO, CSTO, and CIS) and developing effective measures to counter new forms of information threats.

From the standpoint of practical results, it is promising and expedient to continue working on concluding bilateral agreements on cooperation in information security with interested partners. Starting with the USA in 2013, Russia has now signed such agreements with several dozen countries (this topic is covered in a dedicated article in the Volume One of the Security Index Yearbook[33]).

Overall, the field of international information security can be called one of the key arenas for shaping new models of global policy, where civilizational values, technological, economic, and humanitarian interests closely interact with the challenges of the 21st century. New concepts are taking center stage in the Russian (but also in many other countries’) official and expert discourse, such as the notion of digital sovereignty, a category that now supplements state sovereignty. Broadly understood digital sovereignty is the independence of a state in both domestic and foreign policy in the digital sphere, and according to leading Russian experts, it is becoming the most important measure of a state’s viability, security, and economic potential[34]. One of the main tasks and challenges of the Russian government for the coming years will undoubtedly be to ensure that the country is digitally sovereign.

Another key challenge today is the rapid development of artificial intelligence (AI) technologies, which are already penetrating virtually all spheres of life. Russia, seeking to take a leading position in ICT, is now actively formulating its national interests in the field of AI as well. As with ICTs in general one can expect them to blend ambitions for technological sovereignty, economic modernization, military security, and enhanced geopolitical influence through AI development and international partnerships.

[1] Korotkov S. Russia’s independence is directly dependent on the state’s ability to ensure national sovereignty in the information space. // International Affairs Journal. April 4, 2023 URL: https://interaffairs.ru/news/show/39760 (in Russ.).

[2] Foreign Policy Concept of the Russian Federation // MFA of the Russian Federation. March 31, 2023. URL: https://www.mid.ru/ru/detail-material-page/1860586 / (in Russ.).

[3] Fundamentals of the State Policy of the Russian Federation in the field of international information security // MFA of the Russian Federation. 12.04.2021. URL: https://www.mid.ru/ru/foreign_policy/official_documents/1871845/ (in Russ.).

[4] Ibid.

[5] United Nations General Assembly Resolution A/RES/53/70 of December 4, 1998 “Achievements in the field of information and telecommunications in the context of international security” // United Nations. URL: https://digitallibrary.un.org/record /265311 (in Russ.).

[6] Boyko S. International Information Security: Russia in the UN. The beginning of history (1998-2009) // International Affairs Journal. November 20, 2023. URL: https://interaffairs.ru/news/show/43346 (in Russ.).

[7] Letter dated September 23, 1998 from the Minister of Foreign Affairs of the Russian Federation I.Ivanov addressed to the UN Secretary-General K.Annan // United Nations. October 30, 1998. URL: https://digitallibrary.un.org/record/261158 (in Russ.).

[8] Boyko S. International Information Security: Russia in the UN. The beginning of history (1998-2009) // International Affairs Journal. November 20, 2023. URL: https://interaffairs.ru/news/show/43346 (in Russ.).

[9] Report of the Group of Governmental Experts on Developments in the Field of Information and Telecommunications in the Context of International Security (A/70/174) // United Nations. July 22, 2015. URL: https://documents.un.org/doc/undoc/gen/n15/228/37/pdf/n1522837.pdf

[10] On the results of the final meeting of the UN Group of Governmental Experts on International Information Security // MFA of the Russian Federation. June 30, 2015. URL: https://www.mid.ru/ru/foreign_policy/un/1511194/ (in Russ.).

[11] Chernenko E. Digital responsibility will be formalized with a report // Kommersant Publishing House. July 7, 2025. URL: https://www.kommersant.ru/doc/7871382 (in Russ.).

[12] Global Intergovernmental Points of Contact Directory on the Use of Information and Communications Technologies in the Context of International Security // UNODA. URL: https://poc-ict.unoda.org/

[13] Vershinin S. Speech at the round table on international information security within the framework of the XIII International Meeting of High Representatives in charge of security issues, Moscow // MFA of the Russian Federation. May 29, 2025. URL: https://www.mid.ru/ru/foreign_policy/international_safety/2021689/ (in Russ.).

[14] Updated concept of the United Nations Convention on International Information Security // The Security Council of the Russian Federation URL: http://www.scrf.gov.ru/media/files/file/P7ehXmaBUDOAAcATW2Rwa3yNK1bNAWl9.pdf (in Russ.).

[15] On the concept of the UN Convention on International Information Security // MFA of the Russian Federation. May 16, 2023. URL: https://www.mid.ru/ru/foreign_policy/news/1870609 (in Russ.).

[16] Updated concept of the United Nations Convention on International Information Security // The Security Council of the Russian Federation URL: http://www.scrf.gov.ru/media/files/file/P7ehXmaBUDOAAcATW2Rwa3yNK1bNAWl9.pdf (in Russ.).

[17] Ibid.

[18] On the concept of the UN Convention on International Information Security // MFA of the Russian Federation. May 16, 2023. URL: https://www.mid.ru/ru/foreign_policy/news/1870609 (in Russ.).

[19] Vershinin S. Speech at the round table on international information security within the framework of the XIII International Meeting of High Representatives in charge of security issues, Moscow // MFA of the Russian Federation. May 29, 2025. URL: https://www.mid.ru/ru/foreign_policy/international_safety/2021689/ (in Russ.).

[20] For comparison, in the first 48 hours since the start of the signing procedure for the UN Convention against Cybercrime, the number of its participants exceeded 70 countries – Editor’s note.

[21] UN General Assembly Resolution A/RES/74/247 “Countering the use of information and communication technologies for criminal purposes” // United Nations. December 27, 2019. URL: https://documents.un.org/doc/undoc/gen/n19/440/31/pdf/n1944031.pdf

[22] Chernenko E. Not everything fitted under the law // Kommersant Publishing House. January 12, 2024. URL: https://www.kommersant.ru/doc/6452715 (in Russ.).

[23] Ibid.

[24] Chernenko E. A cyber-sensitive topic // Kommersant Publishing House. July 30, 2024. URL: https://www.kommersant.ru/doc/6864552 (in Russ.).

[25] United Nations Convention against Cybercrime; strengthening international cooperation in combating certain crimes committed using information and communication systems and in the exchange of electronic evidence related to serious crimes // United Nations. URL: https://www.unodc.org/unodc/ru/cybercrime/convention/text/convention-full-text.html (in Russ.).

[26] On the Convention Against Cybercrime of the United Nations // MFA of the Russian Federation. December 26, 2024. URL: https://www.mid.ru/ru/foreign_policy/international_safety/mezdunarodnaa-informacionnaa-bezopasnost/1989289/ (in Russ.).

[27] Global Cyber Campaign: a Diplomatic Victory // International Affairs Journal, issue 7, 2021. URL: https://interaffairs.ru/jauthor/material/2529 (in Russ.).

[28] International Internet Governance. (by the Coordination Center for .Ru/.РФ Domains and MGIMO University). Edited by Zinovyeva E. Moscow: 2025 (in Russ.).

[29] Global Cyber Campaign: a Diplomatic Victory // International Affairs Journal, issue 7, 2021. URL: https://interaffairs.ru/jauthor/material/2529 (in Russ.).

[30] Chebakova D. The Russian candidate lost the election of the head of the International Telecommunication Union // RBC. September 29, 2022. URL:https://www.rbc.ru/technology_and_media/29/09/2022/633572c89a79477524f43603 (in Russ.).

[31] Bogdan Martin, a candidate from the United States, was elected the new Secretary General of the International Telecommunication Union // TASS. September 29, 2022. URL: https://tass.ru/mezhdunarodnaya-panorama/15905329 (in Russ.).

[32] Russia will continue to work with the International Telecommunication Union // RIA Novosti News Agency, September 29, 2022. URL: https://ria.ru/20220929/mintsifry-1820305241.html (in Russ.).

[33] Chernenko E. Russia’s Cyber Diplomacy: A Change in Progress // Security Index Yearbook. Vol. 1. 2024-2025. URL: https://pircenter.org/en/editions/security-index-yearbook-chapter-8-russia-s-cyber-diplomacy-a-change-in-progress/

[34] Zinovyeva E., Shitkov S. Digital sovereignty in the practice of international relations // International Affairs Journal, Issue 3, 2023. URL: https://interaffairs.ru/jauthor/material/2798 (in Russ.).