Introduction

Editor-in-Chief

WAR, PEACE AND NO PROPHECIES

Here is Volume Two of the Security Index Yearbook Global Edition, a joint project made by a consortium of two Russian institutions – PIR Center and MGIMO University. MGIMO University of the Ministry of Foreign Affairs of the Russian Federation is a well-recognized university which holds a leading position in the field of international relations. It was founded in 1944 and has significantly broadened the scope of its activities since then, including in the international arena. PIR Center was founded half a century later. It is a compact nongovernmental institution specializing in applied research and analysis of international security sphere.

The cooperation between PIR Center and MGIMO University began three decades ago and has borne fruit since then. It entered a new stage in 2022, turning into the consortium format. It is PIR Center– MGIMO University consortium that, among other materials, publishes Security Index Yearbook series which is the successor to the Security Index Journal, previously published by PIR Center under my guidance and editorial chairmanship.

Thus, Security Index has a solid history and is a well-recognized brand. Still, the year 2024 marks a new milestone in its development: it was then that Volume One of the Yearbook was published. It shared the same format as the edition you are now holding – whether as a paperback or in a digital version available at https://pircenter.org/en/projects/security-index-yearbook/-[1] – and was of equal substantial scope as Volume Two. While focusing on the events of 2022-2023, Volume One also adopted a forward-looking perspective, with its analyses explicitly extending to 2024 and 2025. It is no coincidence that Volume One includes a Part “Forecasting Global Security” with a chapter entitled “Dance of the Little Black Swans”[2]. Volume One, presented to the global audience with public events and expert discussions in Minsk, Geneva, Astana and Zvenigorod, and disseminated in 62 countries aimed at leaders, experts, and universities around the globe, provoked high interest in its contents and demand for a follow-up.

Volume Two reviews key global and regional security developments of relevance to Russia in 2024-2025 and projects forward to 2026-2027. This future-oriented analysis is not only concentrated in the final chapter “Times We Do Not Choose: Leading Powers, Intense Rivalries, and Global Security Landscape” (this was the chapter that I, as Editor-in-Chief, was reading and editing with a particular sense of responsibility for looking at a far distant future), but also permeates the majority of the Yearbook’s other chapters.

For those readers who are familiar with the Yearbook and its Volume One, it is worth noting that the International Editorial Board, chaired by MGIMO University rector Academician Anatoly Torkunov, and the Yearbook’s editorial team under my direction decided to abide by the previously established structure, narrative style and extensive use of infographics while preparing Volume Two.

At the same time, there was no goal to replicate the thematic structure of the previous volume. Instead, we chose a basket of topics deemed most relevant to 2025, the year during which the main work on this edition was conducted. Global concerns including nuclear weapons and the strategic arms control agenda, nonproliferation of weapons of mass destruction (WMD), new types of conventional weapons, outer space, and cyber security are all highlighted in this volume. In terms of regional security, it focuses on Africa, the Middle East, Russia-US, Russia-China, and Russia-Mongolia strategic relations, assessing of prospects for BRICS, and security dilemmas regarding the Korean Peninsula, to name a few. This handbook also reviews a chronology of recent (2024-2025) developments in regional and international security.

What features distinguish Volume Two from its predecessor? Let me outline three of the most salient.

Firstly, it is a deliberate shift away from a Eurocentric security paradigm. Russia is a Eurasian power. Its emblem, the double-headed eagle, gazes with equal intent towards both Atlantic ocean as well as to Indian and Pacific oceans. From the standpoint of Russia’s current interests and future developments, I contend that European security should be viewed in concert with that of Central, South, East and Southeast Asia. This view is echoed by our authors – in particular, by Maxim Ryzhenkov, Minister of Foreign Affairs of Belarus, and Alexander Trofimov, Ambassador-at-Large at the Russian Ministry of Foreign Affairs. Both of the authors explore the contours of a Eurasian security architecture.

Secondly, it is a focus on the intensifying nexus between security and advanced technologies. This volume pays significantly more attention to advanced technologies than the previous one. A dedicated chapter examines how AI and other advanced technologies are reshaping – one might say, in real time – the international security landscape. The security implications of advanced technologies are also thoroughly examined in chapters on space security, international information security and, notably, the future of arms control.

Thirdly, it is a dedicated section on Russia’s strategic cooperation with countries from specific world regions. This volume concentrates on Russia-Africa cooperation, with a particular focus on advanced technologies (two chapters are dedicated to high-tech issues broadly and, specifically, to peaceful nuclear energy). The Volume also analyzes how the ongoing political transformation in the Sahel states affects Russia. In the future we plan to retain this Part on the regular basis profiling Russia’s strategic engagement with a selected world region. Future editions may, for instance, focus on such regions as the Persian Gulf, Latin America or Southeast Asia.

What posed the greatest challenge in preparing Volume Two? The answer is clear for me: it is the extreme volatility and pace of change in contemporary international affairs. As the Russian poet Sergei Yesenin once noted “great things are seen only from afar”. Yet, our editorial team, bound by strict publication schedule, lacks the ability to step back and discern which of the current events will prove truly significant for history and for the future of our planet and which are transient, destined to fade from memory. We are truly aware that some narratives analyzed by our authors in October-November 2025[3] may be viewed from a different perspective in 2026.

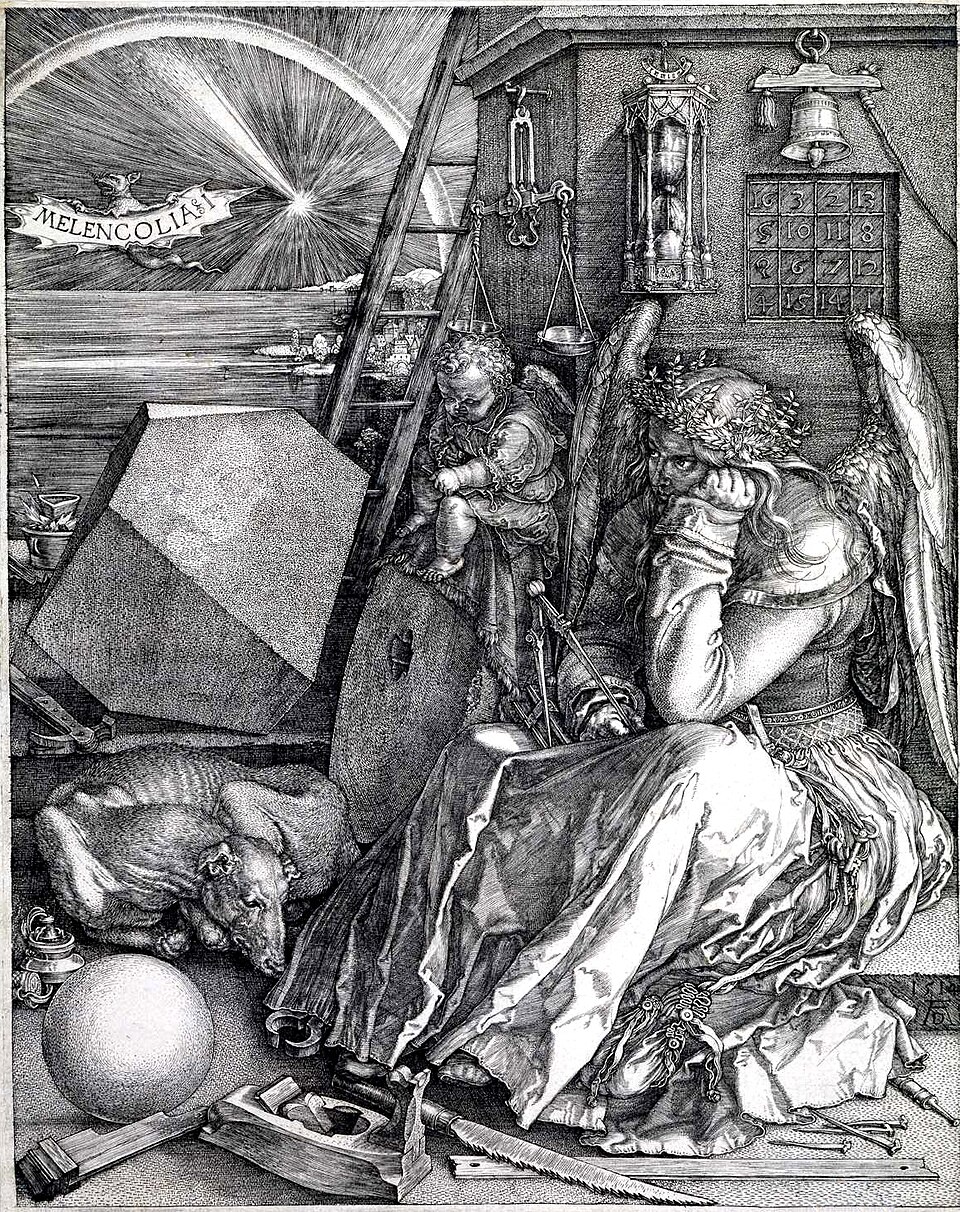

Great dynamism is the parent of turbulence and unpredictability. We do engage in forecasting global trends. Moreover, we do find it necessary. At the same time, we do not practice pseudo-scientific charlatanry through prophecies and divination. Such an approach is banned in our Yearbook. We have therefore chosen the contrary one – it is aligned with the principle articulated by Alexander Pushkin via the character of the chronicler Pimen:

When you are free

From your spiritual feats

Write down unpretentiously[4]

All that you’ll witness in your life:

War, peace, the rule of sovereigns…

It is precisely the principle of unpretentious direct analysis – without much ado! – that has guided our review of the latest global and regional security developments covered in this yearbook.

***

Security Index Yearbook (Vol.2) consists of ten Parts and 29 Chapters.

Part I focuses on particular aspects of global security amid the ongoing transition to a multipolar world. This part includes seven chapters, which cover a wide range of issues related to the Russia’s foreign and security priorities in the context of Special Military Operation, nuclear nonproliferation with its three pillars and arms control, new types of conventional weapons, outer space, artificial intelligence, cyber diplomacy and international information security.

This section opens with Chapter 1 by Dr. Dmitry Trenin dedicated to transformation of Russian approaches to defending national and foreign policy interests in the context of a changing world order. Despite the ongoing conflict in Ukraine and the new risks it poses, Russia maintains a confident posture on the global stage and continues to find new areas of growth.

Chapter 2 by Dmitry Stefanovich focuses on nuclear deterrence and arms control. The author examinesnuclear weapons modernization process, which encompasses delivery systems, nuclear warheads, nuclear command and control infrastructure, as well as doctrinal and conceptual shifts, while also paying attention to rapidly developing hypersonic weapons. What tools will the powers choose to safeguard their interests?

In Chapter 3 Dr. Vladimir Orlov and Sergey Semenov discuss the future of the nuclear nonproliferation regime in the context of ongoing revisions and the gradual erosion of previously inviolable international agreements.

Chapter 4 by Dr. Vladimir Orlov, Sergey Semenov and Dr. Leonid Tsukanov focuses on powers that could potentially, in one way or another, join the so-called nuclear club, having obtained restricted technologies either fraudulently or from gullible sponsors. A notable feature of the Chapter is its application of PIR Center’s open-source intelligence (OSINT) methodology.

Dr. Andrey Malov in Chapter 5 tries to find an answer to the question whether outer space is the domain for peace or arms race. There are several aspects raised in the Chapter, including the challenges to long-term outer space sustainability and militarization of outer space. Special attention is paid to the problem of space debris, which became a new long-term challenge for the leading space states.

Chapter 6 by Dr. Elena Chernenko concentrates on Russia’s cyber diplomacy and its evolution amid the great powers rivalry and the shaping of a multipolar world order. The author examines Russia’s approach to building safe digital space as well as creating global regime of combating cybercrime under the auspices of the United Nations.

Chapter 7 by Dr. Vadim Kozyulin focuses on artificial intelligence and the specifics of its application in contemporary international conflicts. Dr. Kozyulin devotes particular attention to the issue of regulating AI and other dual-use technologies in the context of the development of international humanitarian law. Will artificial intelligence be tamed? And is it really such a good tool for warfare in the new century?

Part II focuses on Russia’s relations with specific countries. The emphasis is placed both on relations with individual states (for example, the United States and China) and on building dialogue with specific regional groups (in particular, with the states of the Middle East). A distinctive feature of this Part lies in the fact that it is not a cross-section of data on Russian Club of friends. Attention is also paid to the prospects of building dialogue with states considered unfriendly.

Chapter 8 by Hon. Maxim Ryzhenkov, Minister of Foreign Affairs of Belarus, focuses on the development of the Eurasian Charter of Diversity and Multipolarity. The new diplomatic initiative launched by Minsk could potentially become the starting point for a new system of security cooperation, supplanting the Helsinki Act. This is especially true given that support for this new approach is being expressed from across Eurasia.

In Chapter 9 Dr. Andrey Kortunov systematizes the lessons of the first months of Russia’s interaction with the Republican administration headed by Donald Trump, who has returned to the White House. The author notes that while significant misunderstandings between Moscow and Washington have been less frequent during the current Trump’s presidency than during Biden’s, Moscow and Washington still remain far from achieving a full-fledged détente.

Chapter 10 by Dr. Leonid Tsukanov is entirely devoted to China – a country that, on the one hand, shares solidarity with Russia on most sensitive issues, yet, on the other, is a potential global competitor. How can we maintain a balance between friendship and rivalry? And what are the specific features of contemporary Russian-Chinese relations?

Chapter 11 by Dr. Elena Suponina explores the specifics of relations between Russia and the Middle East. Skillfully combining historical experience and examples from the contemporary international agenda, the author both explores Russia’s ongoing vital role in the Middle East and underscores the region’s continued strategic significance for Russia.

Chapter 12 by Dr. Alexander Vorontsov takes us to the Korean Peninsula. Over time, the tilt toward the DPRK has become increasingly pronounced, and the author explains why is happened so.

Part III is entirely devoted to the topic of Russia-Africa relations.

In Chapter 13 Dr. Leonid Tsukanov examines the high-tech portfolios of African countries, focusing on the development of digital technologies, space industry, and biotechnology sector. The author emphasizes that despite the exponential increase in the region’s high-tech capabilities, it is still too early to talk about their full-fledged high-tech transition. At the same time, the growing cooperation between African countries and foreign powers (especially Russia) serves as a strong incentive to increase their level of technological readiness.

Svyatoslav Arov continues this line in Chapter 14, dedicated to the development of peaceful nuclear energy projects in Africa. How close is a nuclear renaissance in the region, and why could floating nuclear power plants potentially become a salvation for African energy systems? Answers to these and many other questions can be found in this chapter.

In Chapter 15 Alexandra Zubenko focuses on the Sub-Saharan region and the specifics of building relationships with this group of states in a new era characterized by an increasingly complex threat landscape.

Part IV gives a detailed analysis of specific global and regional issues under a microscope.

From Africa (considered comprehensively and from all sides in Chapters 13-15), we move back to Eurasia. Chapter 16, by Alexander Trofimov, is dedicated to the transformation of international relations in Eurasia. As the largest geopolitical unit, Eurasia is currently becoming the assemblage point of a new international security system. It also serves as a laboratory for testing local approaches to mitigating global threats.

In Chapter 17 Yuriy Shakhov provides a comprehensive examination of Australia’s prospects for joining the nuclear club. Will the transfer of nuclear submarines to Canberra under the auspices of AUKUS remain an innocent Western prank or will it lead to some grave repercussions?

From Australia we move to Asia. More specifically, to Mongolia, which is the subject of Chapter 18 by Roman Kalinin. The author meticulously identifies and systematizes the shifts in Ulaanbaatar’s foreign policy; he identifies areas where contacts between Russia and Mongolia could be particularly effective.

How do international experts perceive the current tectonic shifts in international relations? Dr. Ivan Safranchuk in Chapter 19, drawing on an original methodology offers a vision of the new world order through the lens of various academic schools.

Part V provides dialogues and trialogues with prominent Russian and foreign experts and high-ranking officials.

In Chapter 20 Hon. Sergey Ryabkov discusses the ongoing transformation of BRICS. Over the course of its existence, the format has undergone numerous changes, ultimately becoming a point of attraction for countries around the world. Sergey Ryabkov is optimistic and confident that BRICS can anticipate new diplomatic advances and substantive achievements under India’s chairmanship, which starts in 2026.

Following the topic, we invite to take a closer look at one of the founding members of BRICS: China (Chapter 21). In a conversation with Julia Melnikova and Vladimir Legoyda, the renowned China expert, a former Russian Ambassador to China, Andrey Denisov explores the specifics of Russian-Chinese relations through the lens of culture, ideology, and the mutual perceptions. He also explains how the teachings of the Great Helmsman Mao Zedong can be useful for strategic planning – in the context of both Moscow’s and Beijing’s interests.

Chapter 22 by Amb. Marat Berdyev shifts our focus to APEC. The platform’s formula for success lies in the combination of three key qualities: openness, dynamic development, and viability. These qualities help APEC effectively navigate international crises and flexibly respond to the transformation of the global order.

In Chapter 23 we interview Amb. Dayan Jayatilleka, a prominent Sri Lankan diplomat and scholar. Looking through multiple prisms simultaneously (neo-Marxist theory, Sri Lankan national identity and foreign policy guidelines of South Asian countries), he offers a rather unusual interpretation of the current global transformations.

Chapter 24 focuses on the aspirations of the people of Oceania. What has been the global cost of Western nuclear weapons testing in the 20th century? Why doesn’t remembering the past mean being angry at the world? The former President of Kiribati and the current UN Ambassador Teburoro Tito has the answer.

The concluding chapter of this section (Chapter 25) offers an analysis of recent developments in the Middle East through the lens of personal and professional experience of Academician Vitaly Naumkin, one of the most respected scholars of Oriental studies. Why does the legacy of “Arab Spring” continue to shape the political course of Arab countries, and where can we find the much-vaunted unity? Academician Naumkin, while laconic in his answers, does not leave any question unanswered.

Part VI Back to the Future encompasses three articles which were published in Security Index Journal and other PIR Center’s publications from 2010 to 2024. Why did we decide to include them? Just in order to demonstrate that back then we made an effort to be heard and to signal that the world could go in a wrong direction.

Chapter 26 by Adlan Margoev – leading Russian expert in the field of Iranian studies – is dedicated to the key milestones in the negotiation process surrounding the Iranian nuclear program (including the infamous and now defunct “nuclear deal”). Although originally published in 2024, the text provides a valuable framework for reassessing the approach to the Iranian nuclear dossier.

Chapter 27 chronicles a discussion between two experts, Amb. Sergey Kislyak and William Potter, regarding the prospects for the development and reset of Russian-American relations. Take a closer look at the arguments of 2009, and you’ll suddenly hear echoes of today.

Chapter 28 by Gen. Evgeny Buzhinsky is devoted to an issue without which it’s difficult to imagine any intense conflict today: the use of UAVs on the battlefield and in related sectors. A little over ten years have passed since the original text was published, and the world has changed beyond recognition. The first tentative steps of domestic and foreign UAV developers have already turned into a marathon.

Part VII takes the challenge to look into the near-term future. Dr. Igor Istomin (Chapter 29) outlines the contours of the future and demonstrates that there is nothing new under the sun. When predicting the future, we shouldn’t forget the lessons of the past. After all, we can’t choose our times.

Part VIII includes the reviews of the latest books and research papers published in Russia and by Russian experts and devoted to security issues, regional studies and foreign policy.

Part IX aptly titled “To the Editor: letters from our readers”, summarizes feedback from readers of the Volume One of the Yearbook. In the epistolary style, readers from all over the world express their opinions on covered topics, offer perspectives on the situations described, as well as share insights from their fieldwork.

Part X represents a review of the top events in global and regional security in 2024-2025. The information provided in the Chronology is based on a wide range of different open sources including Russian and foreign media, news agencies, post and press releases as well as official documents, communiques and declarations.

***

After the Volume One of the Yearbook was published, the main question for both the Editorial Board members and me as the Editor-in-Chief was the following: how would readers around the world assess it? Would there be a place for this weighty volume on the shelves of university libraries?

Today, I can say with both confidence and pride: not only was such a place found, but the Security Index Yearbook has pushed aside a number of other English-language publications on the bookshelves, including those that merely pretended to highlight Russian voices and views. In reality, their authors found themselves in an intellectual impasse, repeating well-worn, mossy theses that bore no relation whatsoever to real Russian views and voices, but were convenient for those in the West who dreamed of Russia’s strategic defeat and its disappearance from the world’s political stage. And those of our readers who are open to understanding Russia’s current role and place and its prospects in global affairs not only added the annual to their bookshelves but also shared their impressions.

For example, Colonel Bruno Russi wrote from Bern: «Security Index Yearbook is an indispensable trove. It contains a rare and at the same time extensive selection of authoritative analyses from experts in political, military, government, academic, diplomatic, as well as journalistic fields. It is not only convincing in covering global issues from nuclear weapons, strategic nuclear arms control, cyber space, and international terrorism to lethal autonomous weapons-systems and new conventional weapons-systems but also in presenting Russia’s interests and positions concerning regional security».

Hubert K. Foy from Accra believes that «Packed with expert analysis, this is a practical resource for policymakers, researchers, and anyone curious about global security challenges and how different countries address them». Bruno Rukavina messaged from Zagreb:«The Yearbook’s relevance lies in its function as both scholarship and positioning. While the analyses are clearly shaped by Russia’s strategic worldview, they provide valuable insight into how Russian experts interpret the shifting world order, the failures of Western-led institutions, and the opportunities presented by new partnerships. Its narrative – of a declining West, a rising Global Majority, and Russia as a “security exporter” – may be ambitious, yet it is precisely this alternative framing that makes the volume an essential source of many useful alternative arguments and theses. In an era of fractured dialogue, the Security Index Yearbook offers a rare window into Russian academic discourse and its aspirations for shaping the emerging multipolar system». Abubakar Abdi Osman from Mogadishu is convinced that «Security Index Yearbook is a must-read for anyone seeking to understand the complex and evolving global security landscape», and Philippe Grinenberger adds from Paris that «Security Index Yearbook is an excellent source of information for French civil servants since it provides a different point of view from what is officially said in France»[5].

As Editor-in-Chief, I invite readers of Volume Two of the Yearbook to share with our editorial team their feedback and insights on what you have read, as well as concrete suggestions on how to improve the Yearbook and expand its readership. Please, contact me via email (orlov@pircenter.org). The Editorial Board will analyze and consider your comments, and with your permission, we will publish excerpts from your letters on the Yearbook website and in the next Volume.

***

The productive work on Volume Two of the Yearbook – as well as on this ambitious project as a whole – would not have been possible without the three fronts of support that I have received and continue to receive.

First and foremost, this is the dedicated work of PIR Center’s compact team, from the Chairman of Executive Board, General (Ret.) Evgeny Buzhinsky, to the interns and consultants. To a large extent, PIR Center team and the Yearbook’s editorial team are synonymous. My special thanks go to Dr. Leonid Tsukanov, Executive editor of the Volume Two, for his reliability, comprehensive knowledge, and creative approach, as well as to Elena Karnaukhova, Executive editor of the Volume One, with whom we developed the Yearbook’s structure and design, which we continue to adhere to in this Volume. Her high standards and commitment ensured our new product’s timely release and, overall, a mark of quality.

Secondly, it’s the creative and professional spirit of the authors of this volume and the members of the Yearbook’s International Editorial Board. They all worked with passion, devotion, and responsibility to make this Volume Two a reality. I have enjoyed smooth collaboration with each of the authors and members of the editorial board, and I appreciate their friendly support, whether it came from Cairo, Minsk, Vienna, Stavropol, Yekaterinburg, or New Delhi. I consider this key to the success of our Yearbook.

Last but not least, this is the productive collaboration with our partners at MGIMO University within the framework of PIR Center – MGIMO University consortium and the Priority 2030 program. My special thanks to MGIMO University rector, Academician Anatoly Torkunov, for his unwavering support of our joint Security Index project, for his involvement in the editorial board and its leadership, and for his wisdom.

[1] We wish to advise our readers that the paperback and digital editions of the Yearbook are not entirely identical. The digital edition allows us to present the content of several parts and chapters in greater detail that the paperback one. Certain materials available in digital edition are not included in the paperback edition – Editor’s note.

[2] See: Dmitry Evstafiev. Chapter 29. Dance of the Little Black Swans, pp. 487-504. In:Security Index Yearbook 2024-2025 Vol.1. Global Edition. Vladimir Orlov and Elena Karnaukhova (Editors). PIR Library Series №37. Moscow: Aspect Press, 2024, 575 pp.

[3] The facts and events presented in this Volume are current as of 15 November 2025. In certain cases, where feasible, they have been updated to reflect the situation as of 8 December 2025 when this edition went to press – Editor’s note.

[4] Another translation of this verse from Russian is: “Write down without much ado” – Editor’s note.

[5] For more information about our readers’ feedback and reviews of the Volume One of the Yearbook, see: pp. 413-417 and pp. 449-458 of the Yearbook – Editor’s note.