THE IMEMO SEA POWERS’ RANKINGS 2025

Alexander Polivach, Pavel Gudev

Research paper by the Primakov National Research Institute of World Economy and International Relations of the Russian Academy of Sciences (IMEMO RAS), 2025

ISBN 978-5-9535-0639-7

(published both in Russian and in English)

URL: https://www.imemo.ru/publications/info/morskie-derzhavi-2025-indeksi-imemo-ran

The scientific report Sea Powers’ Rankings 2025, authored by Alexander Polivach and Pavel Gudev and published by the Primakov National Research Institute of World Economy and International Relations of the Russian Academy of Sciences (IMEMO RAS), represents a unique project in the field of international analysis. This paper is not merely a reference book on naval or maritime economic statistics, but a systematic study that offers an original approach to comparing the maritime potential of states amid the rapidly growing competition for resources, control over sea lines of communication, and the resilience of maritime economies.

The authors are experts with profound academic and practical backgrounds. Dr. Alexander Polivach, Senior Research Fellow at IMEMO RAS, is well known as one of the developers of the concept of quantitative measurement of maritime might, while Dr. Pavel Gudev, Senior Research Fellow and Head of the Group on U.S. and Canadian Policy in the World Ocean at the Center for North American Studies of IMEMO RAS, is a leading researcher in maritime geopolitics and security. Their joint work relies on the research and expert base of IMEMO, which lends the report both scientific rigor and applied relevance.

The book is structured as a comprehensive analytical report consisting of six chapters. The first chapter introduces the key indicator – the Index of Maritime Might (IMM-25), composed of three components: the Index of Maritime Resources (IMR), the Index of Maritime Instruments (IMI), and the Index of Maritime Activities (IMA). This tripartite structure captures not only the potential resource base of a state, but also its ability to protect and utilize this base – militarily, economically, infrastructurally, and technologically. The weight of each component in the overall index is clearly defined: IMR accounts for 10%, while IMI and IMA each account for 45%. This proportion underscores the authors’ idea that the mere possession of vast resources does not make a country a sea power: fleet, infrastructure, shipbuilding, logistics, port systems, and merchant shipping are indispensable.

The second and third chapters examine IMR and IMI, respectively. IMR covers controlled waters, exclusive economic zones, and proven offshore oil and gas reserves. Particularly noteworthy in 2025 was the settlement of the UK-Mauritius dispute, which affected the distribution of points in this index. IMI includes 18 categories, ranging from fleet size and naval personnel to submarines, air support, expeditionary capabilities, and military shipbuilding. Central themes include the slowdown in China’s naval shipbuilding and the growth of the U.S. naval index.

Chapter four explores in detail the Index of Navy (IoN) as the core of IMI. This is the most militarized component, where the United States has long maintained uncontested leadership: its navy is twice as powerful as China’s. Russia, though ranked third, shows sharp decline – both in absolute terms and in the trajectory of fleet development. This chapter also contains a forecast extending to 2048, a particularly valuable feature for long-term analysis of naval balance and, to some extent, strategic planning.

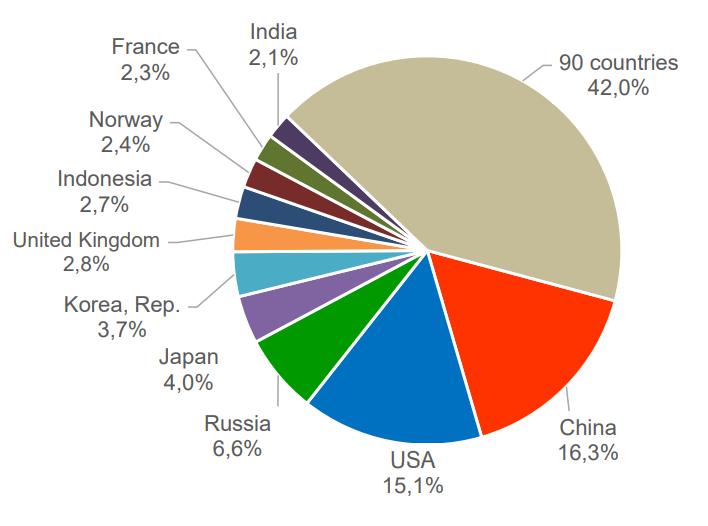

Chapter five is devoted to IMA, the Index of Maritime Activities, where China firmly holds the lead, surpassing the United States by a factor of 5.5 and South Korea by a factor of 4. IMA assesses merchant fleets, port infrastructure, fisheries, marine energy, aquaculture, civil shipbuilding, sailing, and other domains. Here both successes (France and Indonesia) and structural challenges (sharp decline in Japan and the United Kingdom) are visible.

Chapter six addresses methodology. The book clearly explains how the indices are calculated, how the point system operates, and how multi-parameter categories (number and tonnage of vessels) are processed. It also explains how margins of error are treated and how revised versions (v.2, v.3) are produced to reflect updated statistics. This makes the work not only scientifically grounded but also accessible to non-specialist readers, which is rare in such interdisciplinary studies.

Among the key strengths of the book is its comprehensiveness: the authors cover virtually all aspects of maritime power – military, economic, infrastructural, and institutional. This allows maritime might to be seen not as an isolated military category, but as a multilayered phenomenon shaped by the interplay of defense capabilities, trade and logistics chains, energy infrastructure, and scientific and technological development. Another significant advantage is methodological transparency: the index system is fully disclosed, based exclusively on open sources, and regularly updated, including revised versions (v.2, v.3). This enables the data to be used in other research and expert assessments.

Equally important, the research paper does not merely present a static snapshot of maritime power distribution but provides insight into its transformation over time. This makes it possible to trace patterns of growth, stagnation, or decline for particular states, to identify long-term trends, and to anticipate potential shifts. The analysis is also highly geopolitically sensitive, incorporating contemporary events such as Houthi attacks in the Red Sea, the expansion of offshore wind power in Europe, statistical revisions in aquaculture, and sanctions pressure on Russia. This turns It into more than a scientific report: it becomes a tool for understanding current international processes.

The paper carries substantial academic and applied value: it will be useful to scholars in international relations and security studies as well as practitioners – diplomats, military analysts, policy advisers, specialists in maritime logistics and energy. It is a rare example of research that combines scientific rigor with practical analytical utility.

At the same time, the publication is not without shortcomings.

First, despite the wealth of statistics and tables, the visual component remains restrained: there is a lack of interactive or color graphics, maps, and infographics that could ease comparative analysis. Second, although there are select forecasts – for example, on the US and Chinese navies up to 2048 – scenario analysis and projections for most other countries are absent, which diminishes the report’s forecasting potential. Finally, relatively little attention is given to qualitative dimensions of maritime policy – such as diplomatic strategies, legal disputes in maritime law, environmental concerns, and governance of marine resources. Addressing these aspects could further enrich the study and strengthen its interdisciplinarity.

Overall, “Sea Powers’ Rankings 2025” is a truly fundamental work that not only summarizes the maritime dynamics of recent years but also lays the foundation for future research. Its value lies in shaping a new measure of power – one that is defined not merely by the number of aircraft carriers and destroyers, but by resilience, multifunctionality, and the diversity of maritime presence. At a time when the struggle for control of the seas has once again become global and the ideas of Alfred Thayer Mahan[1] remain relevant, such an analytical instrument is particularly in demand.

The work of Dr. Polivach and Dr. Gudev is more than research. It is a contribution to the formation of a modern understanding of what it means to be a sea power in the dynamic and turbulent 21st century.

[1] Alfred Thayer Mahan (1840-1914) is an American naval historian, rear admiral, and one of the founders of geopolitics. A.T. Mahan examines the influence of sea power on the course of history in Europe and America, formulates the patterns of war at sea, and substantiates the theory of “sea power.” According to this theory, achieving supremacy at sea was recognized as the fundamental law of war and the goal of ensuring victory over the enemy and the conquest of world domination – Editor’s note.