On March 13, 2023, in San Diego the leaders of the United States, Australia and the United Kingdom unveiled a plan – first foreshadowed in their earlier announcement in September 2021 – the implementation of which would lead to Australia acquiring a fleet of nuclear-powered submarines (SSNs). It envisages several stages to achieve that[2]. This chapter looks at the AUKUS (Australia-UK-US) nuclear-powered submarines prospects in the context of Australia’s defense strategy. Pillar II of AUKUS, namely the cooperation on advanced military technologies such as quantum computing, artificial intelligence, hypersonic missiles, and cyber security, goes beyond the declared topic of the article and is not considered by the author.

An optimal pathway to deliver SSN capability to the Royal Australian Navy (RAN)

Starting from 2023 RAN’s Fleet Base West in Perth, HMAS Stirling, will see an increased number of visits by the US and later on British submarines. From 2027, they will be forward-deployed there as Submarine Rotational Force – West. Its task is to equip RAN with the necessary skills to operate SSNs.

In approximately ten years from 2023, Australia is expected to receive from the US the supplies of three (and there is an option of two more) Virginia-class submarines to carry out patrols until a more permanent arrangement can be implemented. The first of them will be provided by the US Navy with a remaining life span of about twenty years while the other two will be newly built. Their role will be to close the capability gap of RAN between the decommissioning of its current Collins-class diesel-electric submarines (SSGs) in the 2030s and the acquisition of home-built SSNs.

The latter will involve Australia’s buying into the UK’s program to build the Royal Navy’s next generation of submarines hitherto known as Submersible Ship Nuclear Replacement and henceforth named as SSN AUKUS. In essence, they will be of a British design which is claimed to be 70 percent ready, powered by Rolls-Royce nuclear reactors and at Australia’s request fitted out with the US combat management system, Mk.48 ADCAP heavyweight torpedoes and a vertical launch system for current and future strike weapons and unmanned underwater vehicles[3]. Britain will build the first vessels for the Royal Navy in Cumbria at its Barrow-in-Furness site sometime in the late 2030s. Australian boats are projected to be set afloat by the early 2040s after having been assembled in Adelaide at a new Submarine Construction Yard. Thus, a fleet of at least eight SSNs will take shape under the plan.

Answering the ABC News question about why Australia was going to acquire a British boat instead of continuing to purchase the American Virginia-class, Australian Vice-Admiral Jonathan Mead explained that the US intended to stop building Virginia-class and move on to a new generation submarine in the early 2040s, i.e., at around the same time that Australian Navy planned to be supplied by its home-built SSNs[4]. That would have put Australia for decades to come in a position of building a vessel that no one else was building with the entailing problems in sustainment and supply chain. Instead, synchronized building sequence with Britain provides Australia with a number of advantages including the benefits it may get from the economies of scale, reduced sustainment costs, joint training and basing opportunities, etc. By early 2070s SSN-AUKUS is to begin completing its life cycle of about 30 years, Australia in lockstep with the UK will have had an opportunity to jointly develop and acquire a new model to replace it.

Presenting the rationale for AUKUS to the public, Australian leadership referred to the country’s deteriorating strategic environment and the worsening of regional security and stability. That, as the official narrative goes, required enhanced defense capabilities to make Australia and its partners better able to deter conflict, and help ensure that stability and strategic balance be maintained in the Indo-Pacific. Describing Australia’s strategic landscape, Deputy Prime Minister and Minister for Defense Richard Marles pointed out that while in 2000 China had six nuclear-powered submarines by the end of this decade it would have 21, at the same time the number of its surface ships would increase from 57 to 200. He emphasized the importance of protecting Australia’s long sea routes of communication responsible for the country’s foreign trade which accounts for 45 percent of GDP and vital supplies oil products[5]. What Mr. Marles did not mention in his exposé was that China accounts for one third of Australia’s foreign trade totaling 267 billion Australian dollars, and in case of a military conflict between the two states this money will be instantly lost regardless of the deployment of SSN capability[6]. Also, his explanation was a bit underwhelming since submarines’ role has traditionally been to disrupt enemy communications as part of a sea denial strategy. Conversely, the protection of trade or supply routes in wartime has historically been accomplished by a system of convoys, with merchant ships or troop transports guarded by surface escorts; that has been known in Australia at least since the times of the report on the country’s naval defense made by Admiral of the Fleet Earl Jellicoe in 1919[7].

Indeed, Australia’s current Collins-class submarines were envisaged in the 1980s by the Keating government (1991-1996) as part of an Australia’s defense strategy which focused on guarding the sea-air gap to the north of the continent, a protective moat that separates it from the Indonesian archipelago. In an interview with Australian Strategic Policy Institute, Kim Beazley, defense minister in the Keating cabinet, said that Collins-class submarines had been introduced to protect four maritime chokepoints (straits areas) in the archipelago in order to prevent a potential adversary from attempting the landing of its invasion force on Australia’s shores[8]. In terms of submarines availability, a fair number to accomplish that task, according to Mr. Beazley, was eight vessels, ideally twelve, but budgetary restrictions have reduced this number to only six hulls. As it stands now, a six-vessel fleet provides two submarines available for patrol at any given time, with the other two undergoing training or short-term maintenance, and the remaining two being in long-term refit or repair[9].

In this light it is unsurprising that the Rudd government (2007-2010) in 2009 Defense White Paper requested twelve submarines as the Collins-class replacement. After a competitive evaluation a French-designed attack-class submarine was selected by Australia. Attack-class was cancelled in favor of AUKUS by the Morrison government (2018-2022) in 2021 because of a perceived risk of becoming vulnerable to detection and thus not meeting the criterion of being regionally superior.

While conventionally powered submarines have an established role in the defense concept of Australia, an impending introduction of SSN capability made observers ask the question whether that reflected a paradigm change in underlying strategy. When Defense Minister Richard Marles was probed to give a more realistic explanation of the AUKUS arrangement he emphatically denied that the transfer of American submarines was conditioned by Australia providing military assistance to the US should it come to the exchange of blows with China over Taiwan. At the same time, he did not say that Australia would abandon the US in such a scenario stressing that a relevant decision would be made by the government of the day in Canberra[10].

Thought-provoking reactions

One of the Australia’s outstanding strategists, professor Hugh White, who in the past served as deputy secretary of Defense, could not disagree more. In an article published by the Lowy Institute he expresses his concerns in the following way.

“… AUKUS commits Australia to fight China if America does, simply because the AUKUS deal will be off if we don’t.

That is because America will only sell us Virginia-class boats if absolutely certain that those boats would join US operations in any war with China. They will come straight out of the US Navy’s order of battle, because no extra Virginia-class boats are to be built to meet Australian needs. So, every boat that joins the RAN is one less in the US fleet, and the US Navy is already desperately short of submarines. It is simply inconceivable that Washington would agree to a significant diminution of its submarine capability in this way as its military rivalry with China escalates. So, the Americans must be very sure that any Virginia-class subs they pass to Australia will be available to them when war comes.

Nor will Washington provide the systems and technologies essential to the Anglo-Australian AUKUS-class subs unless our commitment to support America in a war with China is clear. Why else would they take this extraordinary step? Unless Australia is willing to go to war with China, the whole AUKUS deal will not be in America’s interests. So, the Americans must believe that there is, at least, a clear implicit commitment. That commitment will probably have to be made fairly explicit sometime soon if the deal is to proceed. It is hard to imagine that Congress would authorise the transfer of the Virginia-class without firm undertakings.Indeed, AUKUS has only got this far because Washington already takes our commitment for granted.

So, AUKUS is only going to work if the Albanese government plainly acknowledges Australia’s willingness to join America in a war with China. But that is a war that America has no clear way to win, and which may well become a nuclear war. That is one of the many reasons why AUKUS is a dumb idea…”.

Hugh White

AUKUS Commits Australia to Fight China if America Does, Simple

March 22, 2023

Source: Lowy Institute (https://www.lowyinstitute.org/the-interpreter/aukus-commits-

australia-fight-china-if-america-does-simple)

Likewise, former Australian Labor prime minister Paul Keating speaking at the National Press Club in 2021 and again in 2023 offered a powerful public rebuff to AUKUS amid concerns about Australia’s drift towards integrating with US’s offensive strategy vis-à-vis China.

“… the whole point of these hunter-killer submarines is to round up the Chinese nuclear submarines and keep them in the shallow waters of the Chinese continental shelf before they get to the Mariana Trench and become invisible. In other words, to stop the Chinese having a second strike nuclear capability against the United States. This is the game we’re now in. In the Collins game, we were in the defense of Australia. In the Virginia-class game, we are hunter-killing Chinese submarines. This changes our whole relationship”.

“… The Albanese Government’s complicity in joining with Britain and the United States in a tripartite build of a nuclear submarine for Australia under the AUKUS arrangements represents the worst international decision by an Australian Labor government <…> a contemporary Labor government is shunning security in Asia for security in and within the Anglosphere. Australia is locking in its next half century in Asia as subordinate to the United States. And that approach was to have the United States supply nuclear submarines for deep and joint operations against China which supported the United States dominating East Asia …”

“No mealy-mouthed talk of stabilisation in our China relationship or resort to softer or polite language will disguise from the Chinese the extent and intent of our commitment to United States’s strategic hegemony in East Asia with all its deadly portents”.

Paul Keating

Australian prime minister (1991 to 1996)

Sources: The Guardian (https://www.theguardian.com/australia-news/2021/nov/10/it-

would-make-a-cat-laugh-key-moments-from-paul-keatings-national-press-club-

appearance); Official Website of the Honorable Paul Keating

(http://www.paulkeating.net.au/shop/item/aukus-statement-by-pj-keating-the-national-

press-club-wednesday-15-march-2023)

In several respects Mr. Keating appeared to echo the warnings of a former Liberal prime minister Malcolm Fraser who in 2014 advised of the risks of continued alliance with the US and argued in favor of Australia’s armed neutrality and its full Asian future[11].

“We need to make our own decisions. We live in the Western Pacific, our priority should be to carve out better and secure relationships with countries of our immediate region, East and South-East Asia. Instead of showing some degree of strategic independence in our policies, we chose quite deliberately to ally ourselves, and to tie ourselves, much more closely to America’s coat-tails, than ever. This was a major strategic error; a betrayal of Australia’s national interest.

The <…> reason I believe strategic dependence should end is that I do not want Australia to follow America into a fourth war [after Vietnam, Afghanistan and Iraq], blindly, unthinkingly, with little regard for Australia’s national interest, and little regard for our security. A fourth war would be in the Western Pacific. It would likely involve China.

We have interest in a peaceful world, and it is time we begin to cut ourselves off America’s coat-tails. We do not want to be caught between the United States and China. There would be no real winners in such a war. Everyone would lose”.

Malcolm Fraser

Australia’s Role in the Pacific

Source: Asia and the Pacific Policy Studies, 2014. Vol (2). Pp. 431-437

(https://econpapers.repec.org/article/blaasiaps/v_3a1_3ay_3a2014_3ai_3a2_3ap_3a431-

437.htm)

Another former Australian prime minister Malcolm Turnbull voiced his own apprehension of the growing dependence on the US limiting Australia’s freedom of action.

“… While this will, in time, enhance our naval capabilities it will be seen as making us even more dependent on the United States and now the United Kingdom.

Australian sovereignty will be perceived to have been diminished.

Will this make us safer? Will it help stabilise the region? Will it deter coercive, even kinetic, actions by China? We must hope so. Certainly the delivery of submarines decades into the future is hardly likely to impact on Xi Jinping’s plans for Taiwan today”.

Malcolm Turnbull

Address to the Australian Defense College

March 15, 2023

Source: Official Website of Malcolm Turnbull

(https://www.malcolmturnbull.com.au/media/address-to-the-australian-defence-college)

To allay some of the concerns around technological dependency, the Albanese government (2022-present) has been touting the point that future SSNs will have advanced reactors not requiring refueling over their lifetime and thus obviating the need for them to travel either to the US or the UK for refueling. Generally speaking, it is true that the more capability sustainment Australia can do in its future SSN fleet domestically the greater will its sovereign control be. For instance, the sustainment of the current fleet of Collins-class submarines originally developed by Sweden’s Kockums has been highly localized and 92 percent of it is done by domestic supply chain. Still, 8 percent of the content has to be sourced from abroad posing a potential risk of disruption[12]. It is realistic to assume that while the Australian government is trying hard to localize the sustainment of SSN-AUKUS it will unlikely achieve anything similar to self-sufficiency. And this does not even apply to its weapons (torpedoes and missiles) all of which are expected to be provided by the US.

“… For Australia, the stated purpose is to respond to China’s rise, Beijing’s increased aggression and the revelation of Australia’s strategic deficit in a tough neighbourhood. But fundamentally, to achieve security, Australia has historically bandwagoned with one of the region’s great powers in support of a regional and global order balanced in Australia’s favor. <…> the AUKUS program will deter China from pursuing aggressive military options against Australia and will contribute to regional stability by helping to generate a balance of military power”.

AUKUS is Underway, but Key Challenges Remain

Australian Strategic Policy Institute (ASPI)

March 16, 2023

Source: ASPI (https://www.aspistrategist.org.au/aukus-isunderway-but-key-challenges-

remain/)

How AUKUS fits into Australia’s defense posture and planning?

It is true that since the time of federation in 1901, Australia’s defense strategy has been centered around the search for being protected by a great and powerful friend; first, it was the British Empire, and after its defeat in Singapore in 1942 and withdrawal from the Pacific – the United States. This appears to reflect a deeply entrenched anxiety of Australia’s foreign policy elites viewing their country as a small European outpost conceived by the invasion of 1788 and surrounded by an alien Asian world. When the region was affected by colonialism and kept economically backward, that concern was somewhat dormant. In the 1940s, however, Australia’s survival was endangered by an emerging oriental power Imperial Japan that Australia was not capable of repulsing on its own without the recourse to an alliance with the US. That was a hard lesson to be learned. Until this very day it has impacted Australia’s perceptions by instilling them with what the former head of Australia’s Office of National Assessments Allan Gyngell called the fear of abandonment by the US in the region becoming a focal point of great power competition and populated by rapidly rising Asian nations whose capabilities cannot be matched by Australia[13]. As the former defense minister Beazley put it, “I have always thought that survival is very difficult for Australia as the world turns. History has a way of correcting anomalies, and in many ways, we are an anomaly”[14].

Thus, Australia’s establishment is prepared to go to great lengths to ensure that the US will remain the dominant power in the Asia-Pacific and as such will prevent any major challenge to Australia’s security. And if deterrence fails and Australia faces a threat from a major power then the US will defend Australia. AUKUS should be seen in this context as not only integrating Australia even closer with the US Indo-Pacific posture but also as strengthening America’s reassurance to Australia and its commitment to ultimately underwrite its security.

The problem with that approach is that although it worked so well in the past it is not guaranteed that it will work in the future. As the rivalry between the US and China ramps up, some observers such as Professor Hugh White believe that due to the changing balance of forces a US victory in a military conflict with China over Taiwan may not be assured, and such a confrontation runs a risk of escalating into a nuclear war with catastrophic consequences for all stakeholders involved including Australia if it steps into it on the American side. But if it does not, that would likely result in the rupture of the alliance with the US, with Australia being left to its own devices to fend off as best it can.

The prospect of being abandoned unnerves the establishment because throughout its history Australia has always been protected by a friendly superpower of the day. The prevailing orthodox view holds that given its geopolitical surroundings Australia cannot achieve self-sufficiency in defense. That assumption is being challenged, though, by a minority opinion such as Hugh White who in 2019 published a book entitled How to Defend Australia. He questioned conventional wisdom in his analysis of strategies and capabilities. It should be noted that in his view a discussion of Australia’s independent posture without reliance on the US extended deterrence leads to Australia’s contemplations about acquiring nuclear weapons of its own to deter the threat of use or use of nuclear weapons[15].

In examining the feasibility of Australia to become self-sufficient in defense, it may be worth putting things in perspective and provide some relevant comparisons. Australia has a 26 million population, a G20 size economy with a very high GDP per capita and 34 billion US dollars defense budget. Australian Defense Force, an all-volunteer organization, numbers 60.000 active uniformed personnel and 29.750 reserves and is smaller in size than the land forces at 80.000 fighting troops recommended for the defense of Australia by Field Marshal Lord Kitchener in 1910[16]. Australian military analysts such as Professor John Blaxland of the Australian National University, a retired army senior intelligence officer, describe it as a boutique force, i.e., high quality and well-trained but brittle and not suited to be engaged in attritional warfare with a serious adversary[17]. Likewise, the late senator and retired army Major-General Jim Molan, who was Chief of operations for the coalition forces in Iraq, expressed concern about the Australian Defense Force’s casualty-averse approach should it become involved in a high-intensity conflict[18].

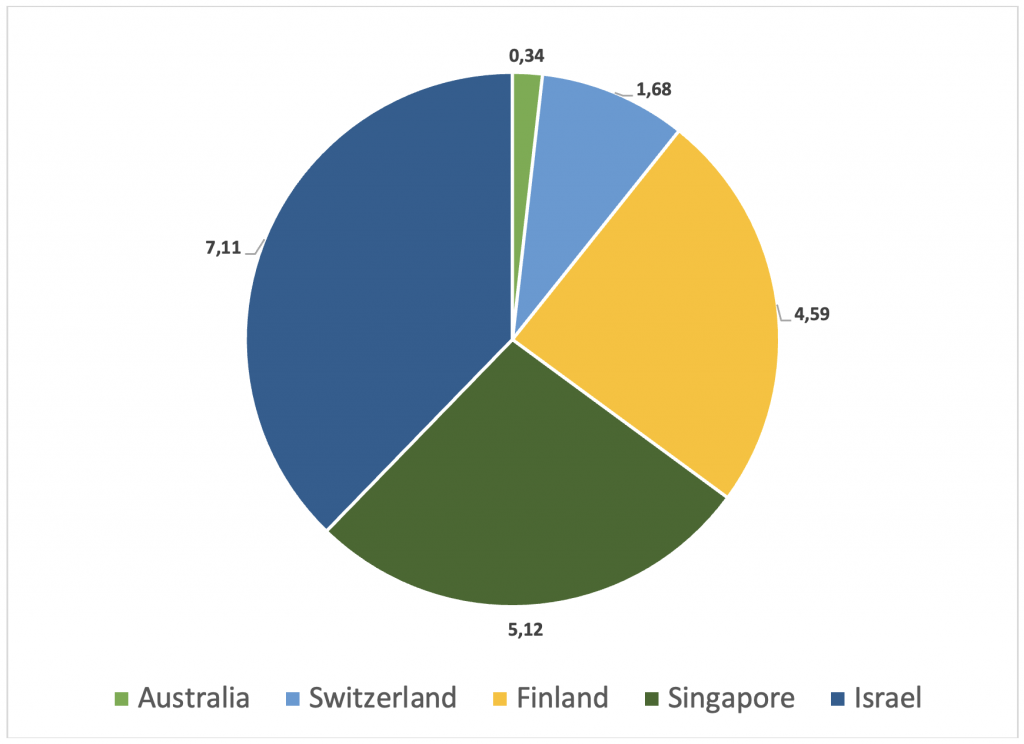

In contrast, two other relatively small and developed countries with comparable levels of per capita income and modern armed forces have a very different posture. With a population of nine million people, Israel has 169.500 active military personnel and 465.000 reserves. Though smaller than most of its regional rivals, Israel can certainly defend itself. Another example is Singapore Armed Forces raised with Israel’s assistance and in some respects modelled after the Israel Defense Forces. With a population of 6 million people, Singapore has 51.000 active military personnel and 252.000 reserves. Both Israel and Singapore rely upon a mixed (volunteer and conscription) manning approach giving them an advantage of fielding much larger forces that can stay in the fight longer than the size of their populations could otherwise suggest. For instance, Singapore’s army has four divisional headquarters while Australia’s has two.

During the Vietnam War (1955-1975) period, Australia heavily relied on a National Service obligation which was a selective conscription scheme allowing it to reinforce its volunteer army with a drafted contingent. National Service was abolished in 1972 and an all-volunteer force has been maintained since then.

In 1999, when the country’s population was 6 million people less than it is now, Australian Parliamentary Research Service produced a paper estimating that the reintroduction of a two-year male-only universal conscription would provide at least 97.000 uniformed personnel boost to the ground forces[19]. Conscription of women was not considered in the study because at that time the army was not allowing their recruitment for direct combat positions (infantry, armor, artillery, and combat engineers), i.e., its core roles. However, since 2013 all such positions have been made available to women, provided they satisfy physical fitness requirements. Therefore, there are no impediments to applying a National Service scheme to women too as is the case in Israel.

Even a male-only National Service intake combined with the volunteer part of the Australian Defense Force which was set by the Morrison government to increase by some 20.000 by 2040 would have grown the army much closer to 180.000 active personnel (and hundreds of thousands in reserve) – the number provided by military chiefs to defense minister Kim Beazley in the 1980s as required for a self-sufficient posture[20].

Historical data also seem to confirm the view that Australia is capable of a meaningful and sustained war effort. In the World War I (WWI) (1914-1918) when Australia’s population was around four million people, 416.809 Australians served in the Army representing 38.7 percent of the total male population aged between 18 and 44. In the World War II (WWII) (1939-1945) with a population of around 7 million people, that number grew to 727.703. For example, by the spring 1943 the Australian Military Forces had totaled nearly 500.000 men and was comprised of two field armies and twelve divisions with a combined strength amounting to about 7 percent of the country’s entire population; the number of divisions was greater in proportion to population than those maintained at that time by Great Britain or the United States[21].

Since the end of the Cold War Australia has been enjoying a peace dividend and the US unipolar moment allowing itself to go below 2 percent of GDP spent on defense as compared to above 3 percent in the 1960s. The strength of the Australian Defense Force as a percentage of population has also shrunk significantly to 0.23 percent compared to 0.40 percent in 1991[22]. However, while the US-led coalition is entering a great power competition posture in Asia-Pacific, as unequivocally recognized by the Chief of the Australian Defense Force General Angus Campbell, it is notable that the Morrison government in its Defense Strategic Update in 2020 advised that Australia could no longer assume a ten-year warning time for a major conventional attack as a basis for defense planning[23]. Kim Beazley expressed the same idea more colloquially in an interview with ASPI: “… we have to be not so laid back”[24].

As we have seen, there is hard evidence in support of the notion that Australia is capable of creating and sustaining an independent self-sufficient defense posture. But adopting it is without a doubt a difficult policy choice and a clear break with the past which at the moment does not enjoy the majority support or even close to it; people like Paul Keating and Hugh White are in a small minority. The option clearly favored by both Labor and Liberal-National Coalition is to double down on the alliance with the US and use AUKUS as a means of cementing it further. If AUKUS, along with other American strategies, fails to deter China it may well contribute to Australia finding itself on a battlefront fighting to preserve the US preponderance in East Asia. John Mearsheimer, Professor of the Chicago University, speaking at Sydney’s Centre for Independent Studies stressed that ‘‘survival is the highest goal any state can have’’[25]. Measured by this yardstick, it is difficult to understand that allowing itself to be part of a looming US-led military action against China over Taiwan fraught with risk of nuclear escalation is in Australia’s best interest.

[1] This chapter is based on the information in the public domain. Some theses were given in the talk on April 6, 2023, in Moscow at the session of the Trialogue Club International The Thucydides Trap: AUKUS and Risks of Military Conflict in the Asia- Pacific. The views expressed are the author’s alone and do not necessarily reflect those of the Ministry of Foreign Affairs of Russia. First published as: Vladimir Ladanov. AUKUS and Australia’s Defence Strategy / Ed. Elena Karnaukhova, Leonid Tsukanov. M.: PIR Press, 2023. – 17 p. – (Security Index Occasional Paper Series). URL: https://pircenter.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/07/SI-INT-3-37-Ladanov.pdf.

[2] AUKUS Nuclear-Powered Submarine Pathway // Australian Government. Australian Submarine Agency. URL: https://www.asa.gov.au/.

[3] Nuclear Submarines Needed due to China’s Military Expansion, AUKUS Task Force Head Says // ABC News Australia. URL: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=DzeDk-ogeR8&t=110s.

[4] Ibid.

[5] Marles: Australia Hasn’t Promised US Support in a Taiwan Conflict // ABC News Australia.

URL: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=8rHZYGz4Muk.

[6] China Country Brief // Australian Government. Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade.

URL: https://www.dfat.gov.au/geo/china/china-country-brief.

[7] Reports of Admiral Jellicoe Volumes I-IV // Royal Australian Navy. URL: https://www.navy.gov.au/media-room/publications/reports-adml-jellicoe.

[8] Lessons in Leadership: The Honourable Kim Beazley AC // ASPI Canberra.

URL: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=MEM4t7PqFMU&t=1408s.

[9] Coles J. Study into the Business of Sustaining Australia’s Strategic Collins-class Submarine Capability, Progress Review // Commonwealth of Australia Department of Defence, 2014. URL: https://www.aspistrategist.org.au/wp-content/uploads/2020/11/Coles_Progress_Review_2016-1.pdf.

[10] Marles: Australia Hasn’t Promised US Support in a Taiwan Conflict // ABC News Australia. URL: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=8rHZYGz4Muk.

[11] Fraser R.H.M. Australia’s Role in the Pacific // Asia and the Pacific Policy Studies, 2014. Vol (2). Pp. 431-437. URL: https://econpapers.repec.org/article/blaasiaps/v_3a1_3ay_3a2014_3ai_3a2_3ap_3a431-437.htm.

[12] Collins Class Submarines: Facts and Features // ASC. URL: https://www.asc.com.au/wp-content/uploads/2021/11/Collins-Class-Facts-and-Features.pdf.

[13] From the Bookshelf: “Fear of Abandonment: Australia in the World since 1942” // The Strategist, October 28, 2021. URL: https://www.aspistrategist.org.au/from-the-bookshelf-fear-of-abandonment-australia-in-the-world-since-1942/.

[14] Lessons in Leadership: The Honourable Kim Beazley AC // ASPI Canberra.

URL: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=MEM4t7PqFMU&t=1408s.

[15] How to Defend Australia // The Strategist, July 2, 2019. URL: https://www.aspistrategist.org.au/how-to-defend-australia/.

[16] Defence of Australia. Memorandum by Field Marshal Viscount Kitchener of Khartoum // The Parliament of the Commonwealth of Australia. URL: https://nla.gov.au/nla.obj-1746277683/view?partId=nla.obj-1753037538#page/n4/mode/1up.

[17] Blaxland J. Hard Lessons from Afghanistan // The Australian, 30 October 2021.

URL: https://www.theaustralian.com.au/special-reports/hard-lessons-from-afghanistan-campaign/news-story/ba0b8fcf639688867bcb92d27641e06c.

[18] Woefully Unprepared for War: Jim Molan’s Critical Warning in Final Must-Watch Interview // Sky News Australia. URL: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=t4fMHyOvtzg.

[19] Brown G. Military Conscription: Issues for Australia // Foreign Affairs, Defence and Trade Group, 12 October 1999. URL: https://parlinfo.aph.gov.au/parlInfo/search/display/display.w3p;adv=yes;orderBy=customrank;page=0;query=Military%20Conscription%3A%20Issues%20for%20Australia;rec=0;resCount=Default.

[20] Lessons in Leadership: The Honourable Kim Beazley AC // ASPI. URL: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=MEM4t7PqFMU&t=1408s.

[21] Australian War Memorial, Second World War Official Histories, Volume VI – The New Guinea Offensives, Volume VII – The Final Campaigns, Appendix 7 – Some Statistics. URL: https://www.awm.gov.au/collection/C1417281, https://www.awm.gov.au/collection/C1417416.

[22] The Cost of Defence, ASPI Defence Budget Brief 2022-2023 // ASPI. URL: https://www.aspi.org.au/report/cost-defence-aspi-defence-budget-brief-2022-2023.

[23] Chief of the Australian Defence Force Delivers AAddress to the Lowy Institute. 10 April 2023 // YouTube. URL: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=PKJcWROv7mo&t=839s.

[24] Lessons in Leadership: The Honourable Kim Beazley AC // ASPI. URL: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=MEM4t7PqFMU&t=1408s.

[25] Can China Rise Peacefully? John Mearsheimer, Tom Switzer // Centre for Independent Studies, August 20, 2019. URL: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=YsFwKzYI5_4; China debate: John Mearsheimer, Hugh White, Tom Switzer // Centre for Independent Studies, August 13, 2019. URL: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=oRlt1vbnXhQ.

E16/MIN – 24/04/15