The history of relations between Russia and China is multifaceted and eventful. Depending on the chosen starting point, it can span either nearly seven centuries (the sporadic and often unofficial contacts between the Russian principalities and the Yuan Dynasty in the first half of the 14th century[1]) or just over three centuries (especially if we start from the signing of the Treaty of Nerchinsk in 1689[2]).

It’s also possible to “start” from early October 1949 – the date when the Soviet Union recognized the legitimacy of the People’s Republic of China (PRC) and became the first global player to establish diplomatic relations with it. With this approach, Russian-Chinese relations have already surpassed the 75-year mark.

Those who are truly sophisticated might take 1991 as a starting point – when, after the collapse of the USSR, Russia (as a successor state) took up the banner of dialogue with the PRC – or 2001, when the Russian-Chinese Treaty on Good-Neighbourliness, Friendship, and Cooperation was signed[3], marking a new era in relations between Moscow and Beijing.

Whatever the starting point, Moscow and Beijing have seen all sorts of things – the two powers have either worked together to counter a common threat, or found themselves on the brink of conflict, or coexisted in a “cold peace”. However, dredging up the past is the job of historians. Our task is to look forward and respond promptly to emerging challenges (while also taking into account the lessons of the past), especially now that the world has passed the “minor equator of the century” (the first quarter of the 21st century) and is entering a new phase.

Friendship in the Age of Black Swans

The third decade of the 21st century, as predicted by Russian experts[4], has proven turbulent: following the global COVID-19 pandemic (for which Western countries continue to blame China[5]) and the subsequent series of economic shocks, the world has faced the thawing of a number of forgotten conflicts – in Africa, Asia, and the Middle East.

The Special Military Operation (SMO), initiated by Russia in February 2022, aimed at protecting the rights of the Russian-speaking population and dismantling the neo-Nazi regime in Ukraine, also brought about adjustments to international relations. The transformation of the global order, which experts have been discussing for the past decade, has accelerated exponentially, as has the division of the international community into opposing camps.

Amid ongoing changes, Russia and China, at first glance, have seemingly maintained the same vector and positive dynamics in their relations as at the beginning of the decade. Their current cooperation can be divided into several groups.

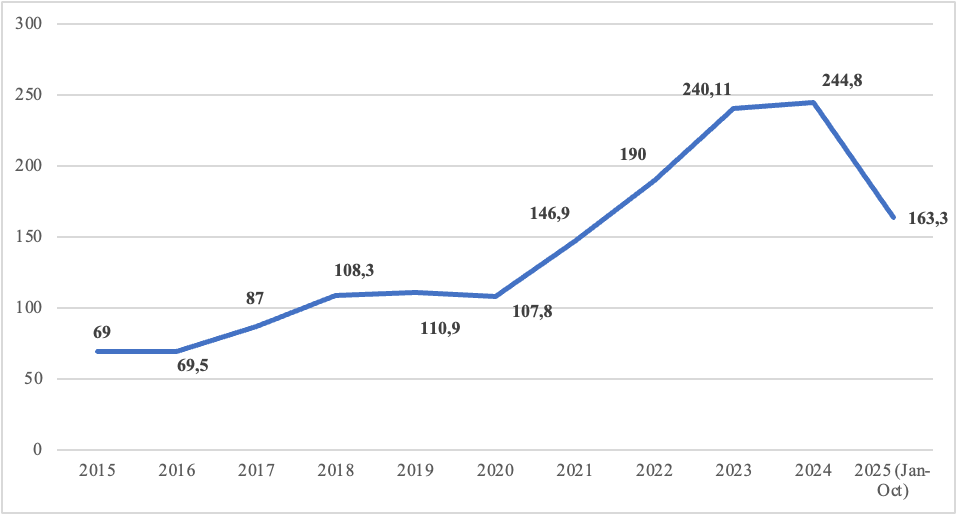

Trade and economic cooperation between Moscow and Beijing is characterized by high dynamism. China remains Russia’s largest foreign trade partner. In 2024, bilateral trade reached a record $244 billion, surpassing the 2023 level of $240.11 billion. Although trade turnover is likely to decline slightly by the end of 2025[6], even by the most pessimistic estimates it is unlikely to fall below the 2022 level of $190 billion. This can be considered a positive result given the growing sanctions pressure on Moscow and Beijing.

As of 2025, Russia’s top export commodities by value are oil, gas, and coal, followed by copper, ore, wood, liquid fuels, and seafood. Most categories (except Russian ore and metals) have declined between 8% and 18% compared to the previous period. Ore and metal exports, on the other hand, have shown explosive growth: from January to September 2025, nickel shipments to China doubled compared to 2024 (to $1 billion), copper increased by 88% (to $2 billion), and metal ores and aluminum increased by 1.5 times (to $2.7 billion). Non-ferrous metals accounted for half of the increase, one-time nuclear fuel shipments accounted for a quarter, and various types of ores accounted for 10%[7].

China exports automobiles, special-purpose machinery, electronics, equipment, and textiles to Russia[8]. Experts estimate that the main decline in Chinese exports is in automobiles and spare parts. Between January and September, they fell to $8.5 billion (down 56% from a record $19 billion in 2024)[9], reflecting a market glut in this category in 2024.

At the same time, Russia and China are working to improve the effectiveness of trade cooperation: through the creation of joint industrial clusters in border areas, the development of R&D, and the expansion of trade and economic contacts in general[10].

Energy cooperation also plays a key role in Russian-Chinese relations. The Power of Siberia gas pipeline, which has been transporting gas from the Kovyktinskoye and Chayandinskoye fields to China since 2019, has become the primary symbol of Moscow-Beijing cooperation in this area[11]. Also, in the autumn of 2025, the actual launch of other major energy projects – the Power of Siberia 2 and Soyuz-Vostok gas pipelines – was announced[12]. Naturally, gas supplies are not the only avenue of cooperation in the energy sector. Moscow and Beijing are developing joint hydrocarbon production projects in the Arctic, advancing initiatives in nuclear and hydrogen energy, and collaborating on joint research in the field of renewable energy.

Furthermore, following the meeting of the heads of government of Russia and China in Hangzhou (November 3, 2025), cooperation was given a new positive impetus: the parties agreed to support the deepening of cooperation between enterprises of the two countries in the oil, gas, coal and electric power sectors, to promote the strengthening of the interconnectedness of energy infrastructure, and to jointly ensure safe and stable operation of cross-border energy routes[13].

It’s not a secret that, given the increased sanctions pressure on Moscow and Beijing, cooperation in the financial sector has grown in importance. Russia and China have been consistently increasing the use of their national currencies in mutual settlements (as of early November 2025, their share in mutual settlements had risen to 99.1%[14]).

Furthermore, both countries are working on developing their own alternatives to the SWIFT system. Russia’s alternative is the Bank of Russia’s Financial Messaging System (in Russian abbreviated as SPFS), while China’s is the Cross-Border Interbank Payments System (CIPS). Since 2023, both systems have been mutually integrated, enabling cross-border payments and thereby reducing dependence on foreign financial platforms[15].

Technological partnership. Russia and China have a solid portfolio of joint technology projects in the ICT and digital security sectors, as well as space and chemical-biological research. However, the emphasis has increasingly shifted toward the joint development of scientific potential. The most recent agreements between Moscow and Beijing demonstrate a commitment to facilitating the joint use of “megascience” facilities, consistently implementing key joint research projects, creating new areas for cooperation, and supporting exchanges between scientists and research institutions[16].

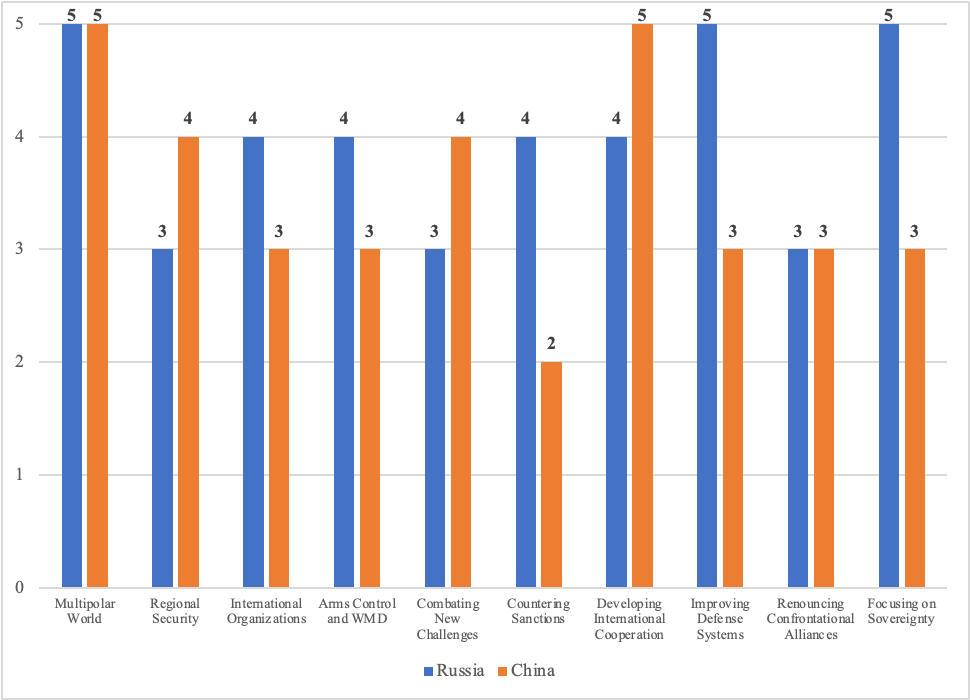

It should be noted that despite the apparent differences in strategic cultures, Moscow and Beijing’s positions in the security sector are quite close: the countries have “consonant approaches”[17] to key international and regional issues. Among the key intersections are the following:

- Focus on building a multipolar security system, respecting the balance of power and interests of the main poles.

- Striving to maintain security in the regions of presence, both internally and with the involvement of regional powers.

- Strengthening the role of international organizations as a link in the system of international relations and modernizing them to meet the challenges of the new era.

- Improving the arms control and nonproliferation system, preventing the erosion of key agreements (NPT, CTBT, etc.).

- Building a proactive system to counter classic and new security challenges.

- Focusing on the comprehensive protection of sovereignty and national identity, preventing interference in internal affairs.

- Rejection of economic sanctions as an instrument of blackmail and pressure.

- Striving to create platforms for cooperation alternative to Western ones (BRICS).

- Rejection of building confrontational alliances.

- Improving national security and defense systems (including the modernization of strategic nuclear weapons).

Moreover, in terms of the frequency with which the parties addressed various security topics, it is clear that China has prioritized developing international cooperation in the area of international security (with an emphasis on the Chinese perspective) and striving for multipolarity. Russia’s priorities, meanwhile, can be characterized by three categories: “sovereignty, multipolarity, and national security”.

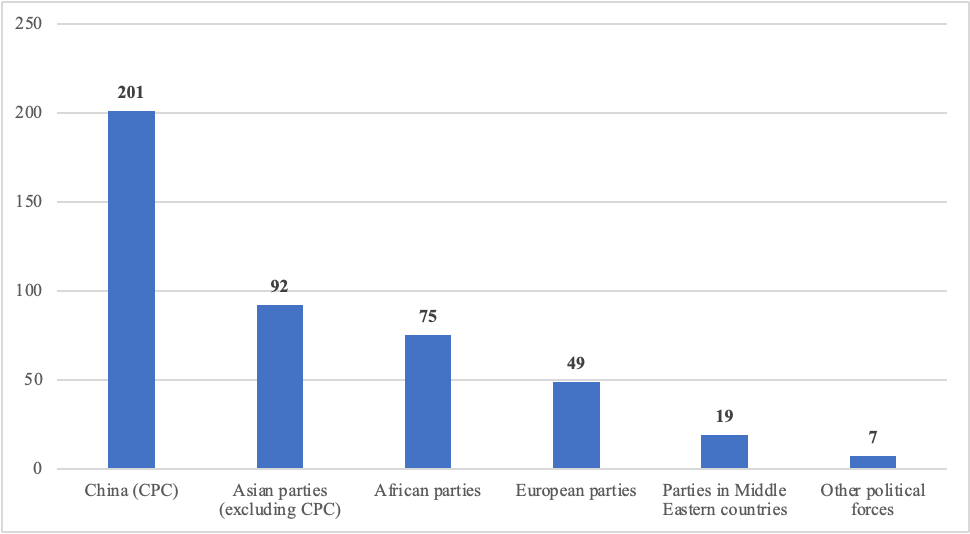

Parliamentary (and inter-party) diplomacy, which both sides are increasingly emphasizing, deserves special mention. In terms of the frequency of contacts with Russian political forces, the Communist Party of China (CPC) is the absolute leader among foreign political forces: over a five-year period (2020-2025), the number of meetings between Russian and Chinese parliamentarians was greater than that of all European, Asian, and African political forces combined[18].

Interestingly, at the inter-parliamentary level, Moscow and Beijing are jointly developing an approach to countering electoral neocolonialism, one of the most obvious threats to countries in the Global South. In the long term, jointly combating this threat should complement the “security basket” being formed to ensure stability in Greater Eurasia.

At the same time, Russian and Chinese elites repeatedly emphasize that Russian-Chinese friendship is not aimed against third countries, but rather at creating conditions for “joint and universal prosperity”[20]. This thesis remains the dominant rhetoric in both Moscow and Beijing.

In the Eye of the Beholder

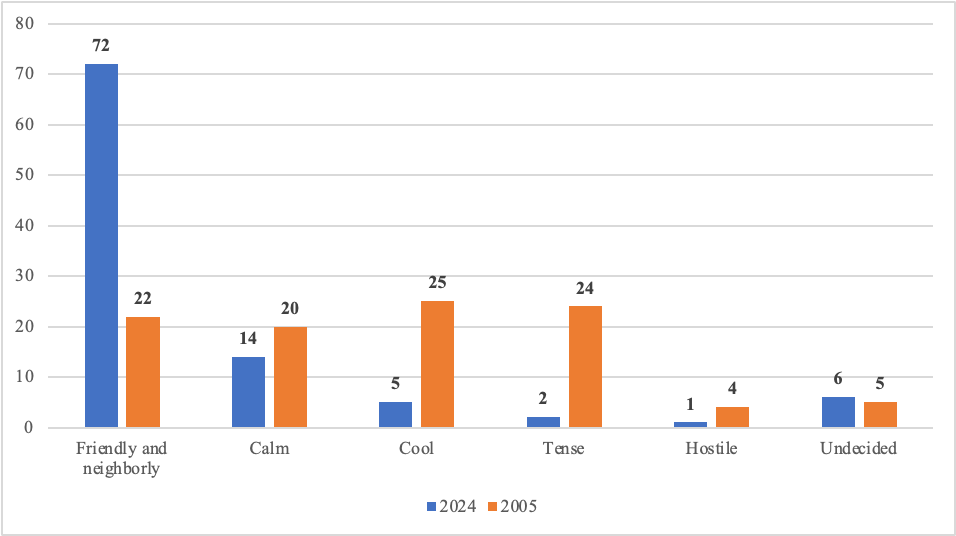

Public opinion surveys reveal a qualitative shift in the attitudes of ordinary Russians toward China over the past few years. For example, the share of Russians who rate relations with China as good-neighbourly has more than tripled over the past two decades (from 22% to 72%), while the number of alarmists (those who tended to see Beijing as an enemy or rival) has decreased more than 6.5-fold (from 53% across all categories to 8%).

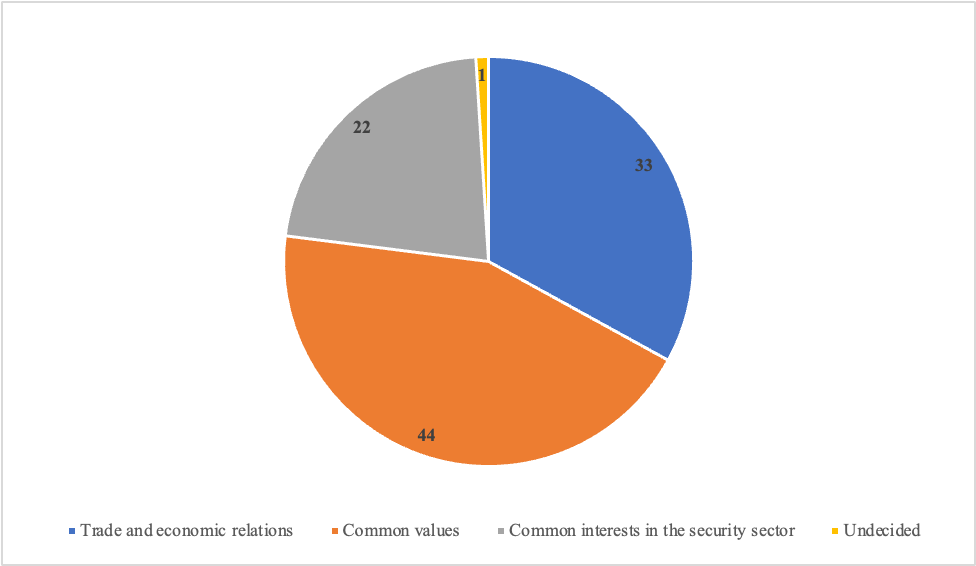

The Chinese view of relations with Russia, however, demonstrates a greater focus not on the nature of the relationship, but on its foundation. It is noted that Chinese counterparts prioritize shared values between Moscow and Beijing (44% of respondents) or trade and economic ties (33% of respondents). Security issues, however, receive the least attention – barely one in five respondents mentioned them.

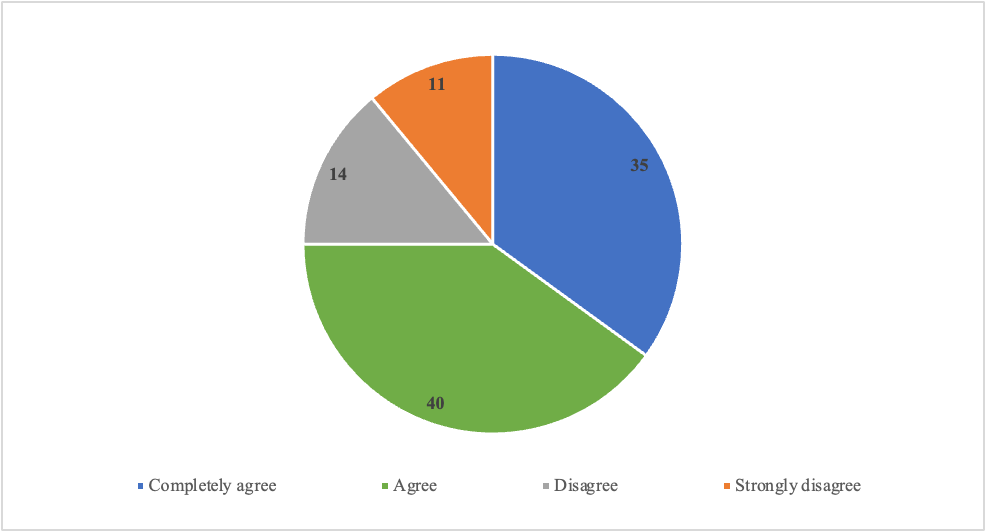

Public opinion surveys (including those conducted by Western think tanks) show that more than 80% of respondents consider Russia a friendly country[21], and this number has increased significantly compared to the early 2000s (when the overall figure barely exceeded 37%).

Commenting on the influence of the SMO factor on international security (and the attitude towards Russia as a participant in this conflict), 75% of respondents expressed support for Moscow’s position in 2022 to one degree or another.

At the same time, a public opinion survey for 2024 conducted by “China-US Focus” and dedicated, among other things, to the attitude of Chinese residents towards the conflict in Ukraine, demonstrated the stability of this position: more than 40% of respondents (42.41%) noted that responsibility for this crisis lies primarily with “third parties” (the US and EU countries)[22].

Breaking the “Porcelain Tandem”

Despite the fact that Russia and China have not given serious reason to doubt the strength of their bilateral relations, their tandem continues to provoke heated debate in international expert communities.

Among other things, the West long held the view that the confrontation with the United States gave a significant (if not decisive) impetus to Russian-Chinese cooperation: Russia entered into a standoff with Washington in 2014, and four years later (during Donald Trump’s first presidential term), the United States initiated a trade war with China. As a result, the two countries found themselves facing a common adversary, against which they “joined forces” – despite previously allegedly demonstrating a “gradual cooling of interest in each other”[23].

Western experts still sometimes like to refer to the Russian-Chinese alliance as “porcelain”, hinting at its fragility and instability in the face of external challenges. At the same time, they extol the role of the United States as a kind of bogeyman for Moscow and Beijing. In other words, the idea was floated that Washington’s reconciliation with either side would automatically put an end to this tandem, which the United States increasingly saw as a threat to its strategic interests.

With Trump’s return to the White House in early 2025, this thesis was gradually elevated to absolute form and projected not only onto relations between Moscow and Beijing but also onto the surrounding geopolitical space. BRICS, which the US president called an “anti-American project”, came under attack in particular[24]. Meanwhile, the idea of separating Moscow and Beijing hasn’t disappeared from the agenda – it’s simply been less talked about, disguised as various “peacekeeping initiatives” under Washington’s auspices. And since a quick reconciliation with Russia based on the Ukrainian track failed to materialize (at least in the format the Republicans had hoped for[25] – including Moscow’s “redirection” toward an economic standoff with Beijing[26]), the United States attempted to shift the focus of détente to China.

The APEC summit in Busan (October 31 – November 1, 2025, South Korea) at first glance appeared to have brought some relaxation to the dialogue between Beijing and Washington. China, among other things, agreed to relax (and eventually completely abolish) export controls on rare earth metals and minimize non-tariff countermeasures against the United States[27]. In return, Washington pledged to revise the phenyl tariff (10%)[28] and extend the moratorium on the additional protective tariff (24%) on Chinese goods until the end of 2026[29]. Furthermore, the two leaders agreed to continue high-level meetings – Trump plans to visit China in April 2026, and Xi is expected to make a return trip to the United States, either to Florida or Washington[30].

Some Chinese experts are also hinting at the advisability of a “thaw” in relations between the US and China. Noting that the meeting between the leaders of China and the US established a relatively equal status for the two countries, creating a balance of power in which neither side can “completely overpower the other” – either politically or economically.

At the same time, talk of the imminent establishment of the notorious Chimerica (China & America)[31], the discussions surrounding which have been ongoing since the mid-2000s, is hardly appropriate at the present time. The reduction in tensions between Beijing and Washington following the Busan meeting should be viewed more as a tactical pause than a permanent and long-term détente. Moreover, the fundamental contradictions between the two countries (including growing trade, economic, and military-political rivalry in other regions) remain unresolved.

Beijing is also mindful of the White House’s shifting mood and is therefore in no rush to change its position on key foreign policy issues. Moreover, joint statements with their Russian counterparts (made after the US-Chinese meetings in Busan) show a more pronounced emphasis on criticizing US attempts to split the established tandem, including through the use of economic and political leverage[32].

…And Other Challenges of the Times

Clearly, the United States isn’t the only thing on earth. Moscow and China’s bilateral relations are also full of their own issues, which (without proper attention) could degenerate into real problems. Let’s briefly examine the most obvious ones.

When discussing the pitfalls of the Russian-Chinese tandem, economic rivalry immediately comes to mind: the interests of Russia and China extend far beyond their national borders and increasingly clash. Of course, the competition is still quite mild – Russian and Chinese business interests generally coexist within the same country. In some cases, the two powers are even collaborating on projects in third countries (for example, the Soyuz-Vostok gas transit pipeline in Mongolia) and are expanding their portfolio of large-scale joint initiatives[33].

At the same time, the balance of power is shifting in certain areas. For example, the export gap between the two countries by the end of 2024 is more than eightfold in China’s favor ($3.57 trillion versus $434 billion) [34]. At the same time, Russia remains the leader, for example, in the construction of nuclear power plants abroad (39 units in 10 countries[35]), while China is currently focusing primarily on building generation facilities domestically (and, moreover, using Russian contractors).

Chinese experts tend to avoid emphasizing the shifting balance of power in regions adjacent to Russia. Although they periodically (often equivocally) say that Russia is gradually losing ground in the “gentlemen’s competition” for Afghanistan, where Chinese private capital is much more widely represented[36]. And in the future, it could similarly lose its dominance in Syria (provided, however, that Damascus heeds Beijing’s key red lines[37]).

At the same time, Moscow’s attempts to “regain influence” in other countries formally within China’s orbit (in particular, North Korea) are perceived by China’s expert community as a “symbolic balancing act” that poses no significant threat to China’s long-term interests. As a result, both sides view the ongoing redistribution of power in regional areas as normal practice and are not particularly eager to interfere with each other.

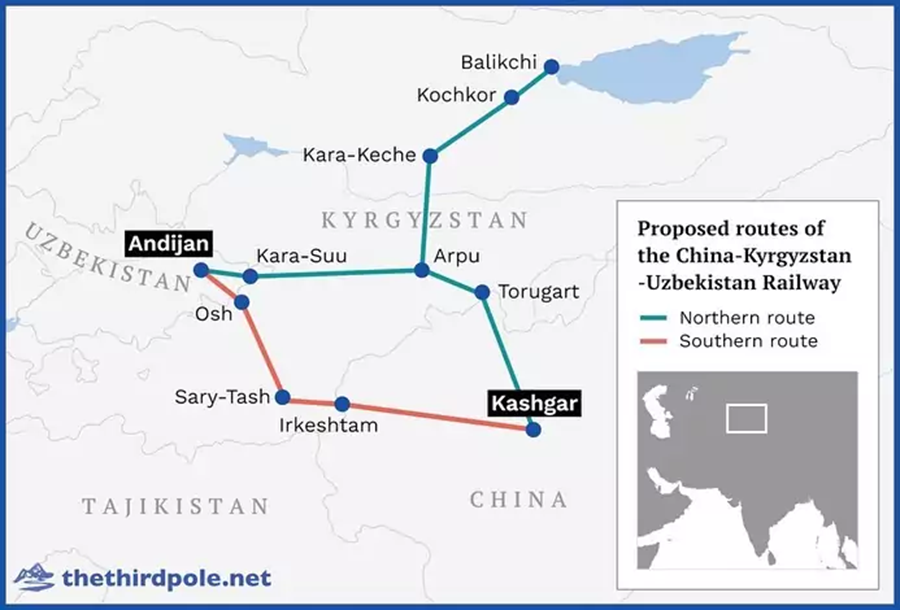

Another sensitive issue being pressed by alarmists is China’s transformation of its approach to developing global logistics routes under the auspices of the Belt and Road Initiative. China is seeking to reduce the time and cost of shipping goods to Europe and is increasingly focusing on the sleeve route through Kyrgyzstan and Uzbekistan (which is 900 km shorter than the route through Kazakhstan and Russia)[38]. This, in turn, threatens to reduce freight volumes via the Trans-Siberian Railway and ports in the Far East, as well as through Russian-Kazakh transport hubs, and, potentially, to relegate Moscow to the periphery of new logistics routes.

However, this fear may be exaggerated: the full launch of the transport route through Kyrgyzstan and Uzbekistan (given the pace of construction and the local landscape) is not expected before 2030. And it won’t be fully operational until 2040. This gives Moscow considerable room to maneuver and leaves the opportunity to take measures to mitigate the economic threat.

The previous point raises the risk of a clash of interests between Russia and China in the Arctic. Beijing (positioning itself as a “near-Arctic” state) continues its rapid advance in the region, considering its economic and political development a key to its status as a leading global power. The Polar Silk Road, part of the Belt and Road Initiative, also runs through the Arctic, demonstrating China’s growing interest in this area.

Despite Moscow and Beijing actively cooperating and developing joint Arctic projects and initiatives (including unique ones, such as the Russian-Chinese commission on shipping along the Northern Sea Route[39]) and positioning each other as “equal players”, China continually tries to steal the show by increasing its investment stake in Arctic projects. While Beijing’s investments have certainly become an important source of funding for oil, gas, and logistics initiatives, reducing the burden on the Russian budget, they also pose the risk of losing control over strategically important projects and facilities. Alarmists constantly point out that Russia could become hostage to Chinese “checkbook diplomacy” and fall into a classic debt trap, sacrificing strategic interests for tactical gains. Even though Moscow retains an absolute lead in icebreaker fleet size (making it the leading force on Arctic Sea trade routes), too much dependence on Chinese capital could weaken its momentum in the region.

The Russian side is seeking to hedge risks – for example, by expanding the pool of investors in Arctic projects and gradually blurring their “national boundaries”. For example, by creating joint initiatives in which, in addition to China, other Arctic players (including the United States) could openly invest. However, this approach is currently primarily limited to public calls and statements and requires time to implement[40].

However, the main vulnerability actually lies elsewhere. China’s approach to the Arctic consensus is more flexible than Russia’s: Beijing is more committed to the internationalization of the Arctic than to establishing control over it (which is not in line with the US) and is reluctant to acknowledge the specifics of Russia’s approach to the region[41]. This could potentially create grounds for disagreement in Russian-Chinese dialogue, and therefore worries Moscow far more than the ephemeral risk of falling into China’s debt trap.

Military and political rivalry is also a potential area of friction. This is especially true as China gradually erodes the boundaries of its “Peaceful Rise” concept[42] (which focused on economic gains) and expands its military portfolio. This is reflected in the expansion of overseas military bases, the development of new strategies for the use of armed forces abroad[43], and an increase in the country’s share of the global arms market.

Beijing is even attempting to compete with other global players for the role of security provider – for example, by weakening US military influence in the Gulf region, which until recently was considered virtually uncontested, and by taking over the role of key mediator in regional conflicts from Moscow and Washington.

Similar trends are also evident in the Sahara-Sahel region, where China is converting its former economic influence into military and political influence, quickly replacing its defunct European competitors (primarily France). China’s increased activity in the Middle East and Africa could pose some threat to Moscow’s long-term interests, but at this stage, it does not clearly conflict with Russia’s foreign policy priorities.

The scientific and technological sector deserves special attention. According to the three technopoles concept, global technological leadership is shared between the United States, China (which is vying for primacy), and the EU. Russia, despite its high level of scientific and technological development, is still playing catch-up[44]. Even allowing for some imperfections in this methodological approach (for example, the authors of the concept overstate the damage to the Russian technology sector caused by Western sanctions after 2022 and also “attribute” some outstanding R&D results to Moscow’s allies), the gap between Russia and China remains significant, and closing it will take time.

At the same time, we can speak of a certain “movement towards each other”: Beijing and Moscow are strengthening cooperation in the scientific and technological sector (with an emphasis on AI technologies)[45]. Moreover, the initiative is coming alternately from both sides, creating a good foundation for further deepening bilateral relations.

The historical claims factor has long been formally removed from the bilateral relations agenda, but external observers (especially those critical of Moscow and Beijing) periodically attempt to bring this issue back to the forefront, citing, among other things, the “complex and convoluted history” of the Russian-Chinese neighbourhood. Meanwhile, the main source of revanchist statements about “historical claims” to Russian cities (as well as claims about the gradual Sinicization of border regions) are social media platforms (such as Weibo)[46], while officials do not address this topic. Furthermore, some of the arguments fueling the myth of China’s growing territorial claims against Russia are being pushed from Taiwan[47], where they are voiced, among others, by top officials of the unrecognized administration and used as a basis for criticism of Beijing’s two-faced foreign policy strategy[48].

In practice, all officially existing territorial disputes between Russia and China were settled back in the mid-2000s – with the signing of the additional agreement between the Russian Federation and the People’s Republic of China on the eastern section of the Russian-Chinese state border[49] – which ensured a broader framework for cooperation “without stones in the bosom”.

Conclusion

Current Russian-Chinese cooperation demonstrates that relations between Moscow and Beijing have withstood the test of major crises without suffering any losses. The parties remain committed to expanding contacts and implementing and expanding joint projects and initiatives (including multilateral ones).

Russia has no intention of deviating from its path in the fight for a just, rules-based world order that respects the interests of its participants, regardless of their geographic location. China is also committed to a “marathon” and is preparing to work toward changing the global balance of power “over the coming decades” – as evidenced, among other things, by the decisions of the Fourth Plenum of the 20th Central Committee of the Communist Party of China[50]. This means Moscow and Beijing will remain on the same path for a long time to come.

As Lao Tzu once said, “A journey of a thousand miles begins with a single step”. And it’s much easier to travel it hand in hand, as Moscow and Beijing are doing today. However, to freely interpret the great Chinese philosopher’s thought, it’s worth adding that Russia and China face many challenges and trials ahead, aimed at testing the strength of their allied ties. These challenges will come from both outside and within.

This means that it is hardly worth expecting an “easy walk”.

[1] Kiriloff, C. The early relations between Russia and China // New Zealand Slavonic Journal, 1969, P. 1–32.

[2] The Treaty of Nerchinsk (1689) – the first official treaty between Russia and China, defining relations between the two states and, in particular, the state border. The terms of the Treaty of Nerchinsk were later revised by the Treaties of Kyakhta (1727), Aigun (1858), and subsequently Peking (1860) – Editor’s note.

[3] Treaty of Good-Neighbourliness, Friendship and Cooperation between the Russian Federation and the People’s Republic of China // President of the Russian Federation. July 16, 2001. URL: http://www.kremlin.ru/supplement/3418 (in Russ.)

[4] Dmitry Trenin. On a New Global Order and Its Nuclear Dimension. An Interview / Ed. Elena Karnaukhova, Leonid Tsukanov. M.: PIR Center, 2023. – 20 p. – (Security Index Occasional Paper Series). URL: https://pircenter.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/03/SI-INT-2-36-Trenin.pdf

[5] White House site blames China for Covid-19 ‘lab leak’ // Le Monde. April 19, 2025. URL: https://www.lemonde.fr/en/international/article/2025/04/18/white-house-site-blames-china-for-covid-19-lab-leak_6740396_4.html

[6] The trade turnover between Russia and the PRC for the first ten months amounted to $163.3 billion, which is 9.5% less than for the same period in 2024. See: 中俄贸易额今年大幅下滑,俄罗斯经济出了哪些问题?(Chinese-Russian trade has plummeted this year. What challenges is the Russian economy facing?) // Kan China. November 5, 2025, URL: https://kan.china.com/article/5415222.html (in Chinese).

[7] Experts explain the decline in Russian-Chinese trade turnover for three consecutive quarters // Vedomosti Newspaper. November 7, 2025. URL: https://www.vedomosti.ru/economics/articles/2025/11/07/1152863-eksperti-obyasnili-snizhenie-rossiisko-kitaiskogo-tovarooborota (in Russ.).

[8] Ibid.

[9] Ibid.

[10] The Future of Russia-China Partnership: From Imports to Joint R&D // RBC. November 5, 2025. URL: https://companies.rbc.ru/news/9m2mMZrj9P/buduschee-partnerstva-rossii-i-kitaya-ot-importa-k-sovmestnyim-niokr/ (in Russ.).

[11] Power of Siberia // Gazprom. URL: https://www.gazprom.ru/projects/power-of-siberia/ (in Russ.).

[12] Miller stated that the Power of Siberia 2 project is already being implemented // Interfax. September 7, 2025. URL: https://www.interfax.ru/business/1046049 (in Russ.).

[13] Russia and China intend to expand their energy partnership // 1Prime Agency. November 4, 2025. URL: https://1prime.ru/20251104/energetika-864199074.html (in Russ).

[14] Siluanov: The share of settlements between Russia and China in national currencies has reached 99.1% // TASS. November 4, 2025. URL: https://tass.ru/ekonomika/25530697 (in Russ.).

[15] China is gradually de-dollarizing // Izvestia Newspaper. November 8, 2025. URL: https://iz.ru/1985865/dmitrii-migunov/vezlivyi-otkaz-kitai-vedet-plavnuu-dedollarizaciu (in Russ.).

[16] Russia and China will cooperate in the field of high technology // RIA Novosti News Agency. November 4, 2025. URL: https://ria.ru/20251104/rossija-2052719429.html (in Russ).

[17] Secretary of the Security Council of the Russian Federation Sergei Shoigu met with Chinese Foreign Minister Wang Yi in Beijing // Security Council of the Russian Federation, November 12, 2024. URL: http://www.scrf.gov.ru/news/allnews/3743/ (in Russ.); China supported Russia’s efforts to ensure security // RIA Novosti News Agency. URL: https://ria.ru/20251104/kitaj-2052717413.html (in Russ.).

[18] Calculated by the author based on open sources.

[19] The data included meetings within the Federal Assembly of the Russian Federation and inter-party negotiations between Chinese representatives and United Russia, the Communist Party of the Russian Federation, the Liberal Democratic Party of Russia, and other systemic parties, as well as meetings between youth organizations.

[20] MFA of the PRC: Cooperation between China and Russia is not directed against any third party and does not depend on external factors // Xinhua News Agency. February 14, 2025. URL: http://www.news.cn/world/20250214/be815ef7ffd345dea4c78ebb5ed488e3/c.html (in Chinese); Russia and China have stated that their relations are not directed against third countries // Interfax. November 5, 2025. URL: https://www.interfax.ru/russia/1056247 (in Russ.).

[21] By comparison, Russia was considered a friendly country by approximately 83% of respondents. This figure is higher than for North Korea (76%), Australia (51%), and the EU countries (50%). See: Friends with Benefits: Chinese See Russia and North Korea as Beijing’s Closest Comrades // Chicago Council on Global Affairs. September 2, 2025. URL: https://globalaffairs.org/research/public-opinion-survey/friends-benefits-chinese-see-russia-and-north-korea-beijings-closest

[22] Also, 16% of respondents blamed Ukraine for inciting the conflict (while less than 6% blamed Russia). See: 民意调查报告 中国人的国际安全观 (Public Opinion Survey Report: Chinese People’s Perspective on International Security) // China-US Focus, 2024. URL: https://www.chinausfocus.com/publication/2024/2024-Chinese-Outlook-on-International-Security-CN-CISS.pdf (in Chinese).

[23] The Enemy of My Enemy is My Friend: Russia-China Relations in the Face of U.S.-China Tensions // Institute for Security and Development Policy. August 17, 2020, URL: https://www.isdp.eu/the-enemy-of-my-enemy-is-my-friend-russia-china-relations-in-the-face-of-u-s-china-tensions/

[24] For more details on BRICS, see Chapter 20 of the Yearbook – Editor’s note.

[25] For more details on the specifics of relations between Moscow and Washington in the first months after Trump’s return to the White House in 2025, see Chapter 9 of the Yearbook – Editor’s note.

[26] Russian Foreign Minister Sergey Lavrov on relations with the US, EU, and Ukraine // Kommersant Publishing House. October 15, 2025. URL: https://www.kommersant.ru/doc/8120945 (in Russ.).

[27] On the sidelines of the trade war: how Donald Trump and Xi Jinping met // Forbes, November 1, 2025. URL: https://www.forbes.ru/mneniya/549068-na-polah-torgovoj-vojny-kak-prosla-vstreca-donal-da-trampa-i-si-czin-pina (in Russ.).

[28] Ibid.

[29] Following Trump’s steps, the overall value of tariffs on China has dropped to 47%.

[30] On the sidelines of the trade war: how Donald Trump and Xi Jinping met // Forbes, November 1, 2025. URL: https://www.forbes.ru/mneniya/549068-na-polah-torgovoj-vojny-kak-prosla-vstreca-donal-da-trampa-i-si-czin-pina (in Russ.).

[31] Chimerica – a neologism coined in 2007 by British historian Neil Ferguson and German economist Moritz Schularick. The term describes the symbiotic relationship between China and the United States. While primarily an economic term, it also has political connotations. The term replaced Nichibei – a similarly structured Japanese-American economic model and relationship that existed in the second half of the 20th century.

[32] Russia and China have spoken out against bullying in the global economy // Interfax. November 4, 2025. URL: https://www.interfax.ru/business/1056252 (in Russ.); China’s Foreign Ministry: Putting pressure on Russia will not resolve the Ukrainian crisis // Vedomosti Newspaper. October 23, 2025. URL: https://www.vedomosti.ru/politics/news/2025/10/23/1149158-mid-kitaya (in Russ.).

[33] Russia and China plan to collaborate on fourth-generation nuclear energy // TASS. November 3, 2025. URL: https://tass.ru/ekonomika/25527347 (in Russ.); Russia and China have begun developing a nuclear power plant for a lunar station, RBC. May 8, 2024. URL: https://www.rbc.ru/politics/08/05/2024/663b16249a7947453c5f1ea7 (in Russ.); Construction of an interstate cargo port has begun on the border between China and Russia // RBC. August 23, 2025. URL: https://www.rbc.ru/rbcfreenews/68a9898d9a7947275101e147 (in Russ.) etc.

[34] China increased exports by 7.1% and imports by 2.3% in 2024 // Interfax. January 13, 2025. URL: https://www.interfax.ru/business/1002543 (in Russ.); Russia’s trade balance increased by 7.8% in 2024 // Interfax. February 26, 2025. URL: https://www.interfax.ru/business/1010906 (in Russ.).

[35] Nuclear power plants under construction // Rosatom. URL: https://rosatom.ru/production/design/stroyashchiesya-aes/ (in Russ.).

[36] 朱永彪:相对宽松的国际环境能否促进阿富汗现代化?塔利班需要作出回答 (Zhu Yongbiao: Can a relatively relaxed international environment promote the modernization of Afghanistan? The Taliban needs to answer this question) // Guancha. October 2, 2025. URL: https://www.guancha.cn/zhuyongbiao/2025_10_02_792101.shtml (in Chinese); China Institute of Contemporary International Relations. URL: http://www.cicir.ac.cn/new/opinion.html?id=1f023220-43a5-4624-9f18-2f9fbd447a64 (in Chinese)

[37] One such “red line” is the disarmament of the so-called “Uyghur Guard” (the 84th Special Forces Division of the Syrian Armed Forces, approximately 3,500 men), the backbone of which is made up of former militants of Uyghur origin. Damascus refuses to disarm this unit.

[38] The Window Is Closing: How China Is Building Transport Corridors Bypassing Russia // Forbes. November 6, 2025. URL: https://www.forbes.ru/mneniya/549258-okno-zakryvaetsa-kak-kitaj-stroit-transportnye-koridory-v-obhod-rossii (in Russ.).

[39] Russia and China will create a commission to develop the Northern Sea Route // TASS. March 16, 2024. URL: https://tass.ru/ekonomika/20819733 (in Russ.).

[40] RDIF: Russia is considering joint projects with China and the United States in the Arctic // TASS. September 2, 2025. URL: https://tass.ru/ekonomika/24930723 (in Russ).

[41] After February 2022, Russia tightened navigation regulations within its internal waters in the Arctic Ocean, regulated the passage of warships, updated the set of coordinates for defining straight baselines (the boundaries of the internal sea), and received approval for its bid to expand its continental shelf. Beijing, meanwhile, adhered to its 2018 position “on protecting all countries and the international community” (White Paper, 2018). See: Zhilin R. China and the Peculiarities of Russian Sovereignty in the Arctic // Russia in Global Affairs Journal. September 9, 2024. URL: https://globalaffairs.ru/articles/kitaj-i-arktika-zhilin/ (in Russ.).

[42] Peaceful Rise – is the official policy and political slogan of the PRC, implemented under former General Secretary of the Communist Party of China Hu Jintao. This slogan was intended to reassure the international community that China’s growing political, economic, and military power would not pose a threat to international peace and security – Editor’s note.

[43] Goncharenko A. China’s Hybrid Warfare Strategies: A Western Perspective // International Affairs Journal, 2022. URL: https://interaffairs.ru/jauthor/material/2694 (in Russ.).

[44] Schmid S., Lambach D., Diehl C., Reuter C. Arms Race or Innovation Race? Geopolitical AI Development // Geopolitics. 2025. Vol. 30. Iss. 4. P. 1907–1936. https://doi.org/10.1080/14650045.2025.2456019

[45] See e.g.: Russia and China are ready to work on the creation of a Global AI Organization // RIA Novosti News Agency. November 4, 2025. URL: https://ria.ru/20251104/rossija-2052719841.html (in Russ.).

[46] Why Russia’s Vladivostok celebration prompted a nationalist backlash in China // the South China Morning Post. July 2, 2020. URL: https://www.scmp.com/news/china/diplomacy/article/3091611/why-russias-vladivostok-celebration-prompted-nationalist

[47] Russia does not recognize Taiwan as an independent state and considers it an integral part of China – Editor’s note.

[48] If China wants Taiwan it should also take back land from Russia, president says // Reuters. September 2, 2024. URL: https://www.reuters.com/world/asia-pacific/if-china-wants-taiwan-it-should-also-take-back-land-russia-president-says-2024-09-02/

[49] In accordance with the agreement, China received a number of territories with a total area of 337 km², including a plot of land in the area of Bolshoy Island (the upper reaches of the Argun River in the Chita Region) and two plots of land in the area of Tarabarov and Bolshoy Ussuriysky Islands in the area of the confluence of the Amur and Ussuri Rivers. See: Russia and China have completed the legal process of delimiting their common state border // President of the Russian Federation. October 14, 2004. URL: http://en.kremlin.ru/events/president/news/31925

[50] 中国共产党第二十届中央委员会第四次全体会议公报 (Communiqué of the Fourth Plenary Session of the Twentieth Central Committee of the Communist Party of China) // Government of the PRC. October 23, 2025. URL: https://www.gov.cn/yaowen/liebiao/202510/content_7045444.htm (in Chinese).