The Treaty on the Non-Proliferation of Nuclear Weapons (NPT) and the nuclear nonproliferation regime based on it are undoubtedly the pillars of the modern global security system. This is all the more striking given that the Treaty’s imminent collapse has been predicted almost since its signing in 1968, implying that politicians’ desire to gain universal leverage (which is nuclear weapons) will sooner or later prevail over common sense.

There have indeed been occasions to take the alarmists at their word – whether it was India and Pakistan’s unauthorized entry into the Nuclear Club, North Korea’s withdrawal from the NPT, Iran’s and South Africa’s secret military programs, and so on. However, the international community managed to dismiss these incidents as isolated, preventing mass nuclearization.

However, the situation has changed over time, not for the better: the increasing level of conflict in the world, coupled with the escalation of old conflicts (the Indo-Pakistani standoff, the conflict between Iran and Israel, rising tensions in the South China Sea, etc.) – all this provokes repeated attempts to revise the global nuclear status quo. However, for many, this remains limited to the rhetorical question “What if…” – the checks and balances generally work.

The clash of swords is becoming increasingly clear from Europe as well – hawks, dreaming of reconsidering their country’s place in the global security system, are preparing to arm themselves. Moreover, they are arming themselves collectively, under the umbrella of the European Union—calling it, with the flexible term,Eurodeterrence. And hiding behind the convenient guise of the “Permanent Russian threat”, of course.

However, Nomina sunt odiosa[1]. It’s important not to blame individual minions, but to look ahead, promptly identifying dangerous trends and nipping them in the bud. Especially since not all potential candidates for the Nuclear Club are vocal about their intentions. There are those who maintain their silence and commitment to the NPT regime to the very end, while simultaneously gathering strength in case a decisive breakthrough is required.

This chapter is based on upcoming volume of PIR Center’s collective expert study, which analyzes, using open sources, the nuclear weapons capabilities of several “threshold” states: South Korea, Japan, Ukraine, Türkiye, Iran, Saudi Arabia, Australia, and Germany. It also examines current trends in the NPT review process and debates around the prospects for European deterrence. A summary of its key points is provided below.

South Korea: First Among Equals?

The Republic of Korea (ROK) is among the most obvious candidates to become the next nuclear-weapon state.

In terms of formal doctrinal guidelines, Seoul remains committed to the nuclear nonproliferation regime. Gaffes by relevant South Korean officials regarding the development of their own nuclear arsenal are muted[2]. Moreover, during a recent meeting with US President Donald Trump, South Korean President Lee Jae-myung emphasized that his country has no plans to develop nuclear weapons.

Currently, the Republic of Korea truly lacks the necessary political capacity for nuclear sprint. For example, the country lacks domestic uranium mining, uranium enrichment facilities, or spent nuclear fuel reprocessing facilities. Therefore, the key challenge for implementing a military nuclear program – obtaining sufficient fissile material – has not been resolved. Implementation of the relevant stages of the nuclear fuel cycle is hampered by the provisions of the 2015 US-South Korean 123 Agreement[3]. There is also no reliable information on theoretical nuclear weapons research or the development of non-nuclear components for special munitions.

Conducting OSINT research is fraught with two potential pitfalls. The first is the echo effect, when information from a single source spreads rapidly. In this case, there’s a temptation to assume it’s reliable due to the large number of publications. It’s important to remember that the desire to confirm an already formed opinion is one of the mental distortions inherent in the human psyche.

The second pitfall is the tendency for unreliable information to spread rapidly, which also clouds the information space.

“Methodology and Practice of Open-Source Intelligence (OSINT) for

International Security, Arms Control, and WMD Nonproliferation Studies”

https://pircenter.org/editions/methodology-osint/

At the same time, the Republic of Korea has a solid foundation for the rapid launch of such a project. The country operates 26 nuclear power units, has established nuclear fuel production, and has developed its own technologies in both uranium enrichment and radiochemical reprocessing of spent nuclear fuel. Tens of thousands of nuclear specialists have been trained, and scientific and technical capabilities have been established, including for the fabrication of high explosive lenses and the associated automation used in nuclear munitions.

ROK’s wide range of missile systems, including submarine-launched ones, deserves special mention. In 2021, Seoul succeeded in lifting US-imposed restrictions on the range of domestically produced missiles. According to open media reports, the most powerful South Korean missile (Hyunmoo-5) currently has a range of approximately 3,000 kilometers and a payload of up to 8 tons[4].

It appears that the South Koreans are diligently preparing the technical and ideological foundation that could support the political decision to develop nuclear weapons. In this context, Seoul’s attempts to secure US support for the development of its own nuclear submarine are noteworthy. An agreement to hold substantive consultations on this issue was reached during the US-South Korean summit in October 2025.

Another sign of change is the announced negotiations to lift the aforementioned restrictions on South Korea’s nuclear fuel cycle programs. If such an agreement is reached, the Republic of Korea will pave the way for itself to obtain the fissile material needed for nuclear weapons.

The target of potential nuclear deterrence in South Korea is clear: the Democratic People’s Republic of Korea (DPRK), an ally of our country. However, the actual dynamics of Seoul’s advancement toward a strategic arsenal will depend not on Pyongyang’s specific actions, but on the perceived reliability of the American nuclear umbrella. It is important to emphasize that the US-ROK alliance, according to the 2023 Washington Declaration, already has nuclear status, and its evolution toward enhanced extended deterrence formats, modeled on NATO’s joint nuclear missions, would in any case pose a threat to Russian interests.

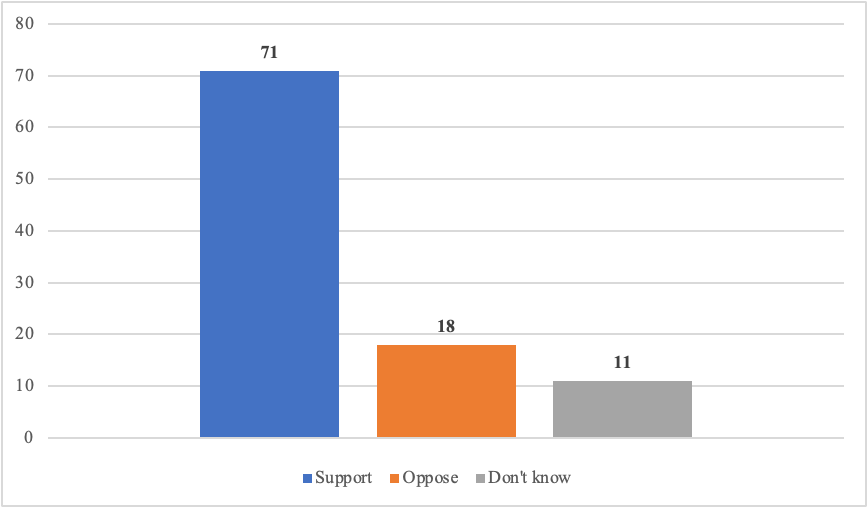

Basic public acceptance of the nuclear option, given the simmering inter-Korean conflict, has been established. According to public opinion polls, approximately 77% of South Koreans support developing their own nuclear weapons. However, these figures reflect more emotion than substance. A survey of South Korean academics and experts shows that actual support, given the risks to the alliance with the US, is around 30-40%.

The further evolution of Seoul’s nuclear policy, as already noted, will depend on the dynamics of relations with the United States. At the same time, concerns about possible sanctions from Washington appear to be less pressing than they once were. Given the importance of the bilateral alliance, there is no guarantee that the Americans, in the event of another rebalancing of their interests, will take effective measures to prevent South Korea from acquiring its own nuclear weapons or to punish it for such aspirations.

In these conditions, from the nonproliferation standpoint, a coordinated response from ROK’s neighbours in the region, and above all, Russia and China, is of key importance.

Japan: Under the Shadow of the Past

The analysis shows that Japan remains far from developing its own nuclear weapons, despite statements from right-wing Japanese politicians (nuclear hawks), including the current prime minister. Anti-nuclear sentiment in Japanese society and the lack of a clear strategic deterrent requirement comparable to South Korea’s currently keep Tokyo in the non-nuclear camp.

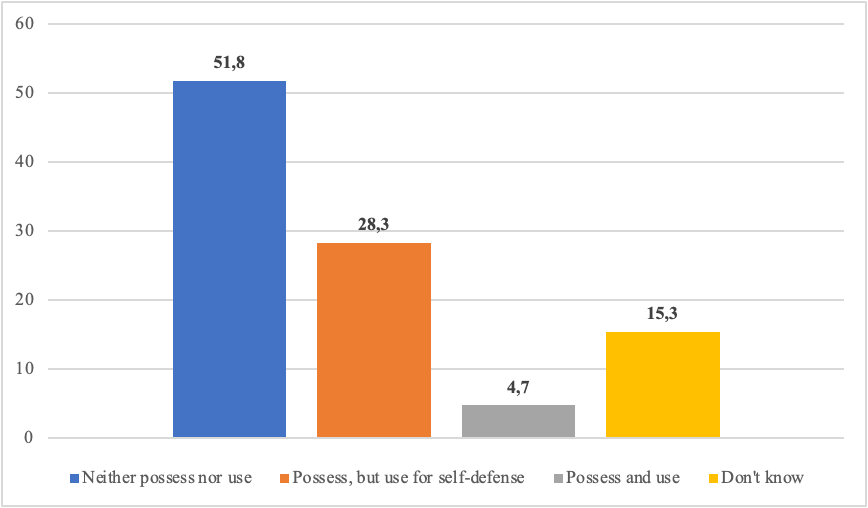

It should be noted that, according to sociological surveys, the majority of Japanese people remain anti-nuclear. For example, 51.8% of those surveyed by the Japanese Red Cross Society (June 2025) opposed Tokyo’s acquisition of nuclear status. It is also noteworthy that 28.3% of respondents consider the possession of nuclear weapons for self-defense inevitable, and 27.3% consider nuclear weapons an effective deterrent[5].

Over the past 10 years, this represents a gradual increase in support for the concept of nuclear deterrence in Japanese society. In 2015, only 10.3% of respondents believed the US nuclear umbrella was necessary to maintain security[6]. In 2020, three-quarters of respondents also supported Japan’s accession to the Treaty on the Prohibition of Nuclear Weapons (17.3% opposed)[7].

The trend toward increasing public acceptability doesn’t play a dominant role. Japanese society still appears to live in the shadow of Hiroshima and Nagasaki, and there’s no clear demand to abandon the three non-nuclear principles. At the same time, the topic of nuclear weapons is no longer taboo. Right-wing experts and politicians are inclined to further hype the nuclear issue to boost their popularity.

In terms of technical capabilities, Japan has everything it needs. In the context of its military-applied nuclear program, the planned launch of the spent nuclear fuel reprocessing plant in Rokasho in 2027 and the expected delivery of American Tomahawk cruise missiles to the Land of the Rising Sun are noteworthy.

The current primary scenario is maintaining a non-nuclear status while simultaneously strengthening the American presence and possibly strengthening trilateral coordination with Seoul and Washington on nuclear issues. However, should relations with these capitals deteriorate, the real marker of the Japanese leadership’s plans will be, at the political level, further mobilization of public opinion in favor of abandoning the three “non-nuclear principles”, and, alternatively, attempts to return plutonium stockpiles stored in France and the UK—possibly under the pretext of fabricating MOX fuel (such plans already exist) to expand the national nuclear energy program.

Ukraine: Empty Vessel Makes the Most Noise

In 2024-2025, Ukraine continued to “warm up” public opinion about the possibility of developing its own nuclear weapons. In this context, it’s worth highlighting both Volodimir Zelenskyy’s statements about the need to acquire a strategic missile defense system in case Kiev is not accepted into NATO, as well as expert publications asserting Ukraine’s significant nuclear weapons potential.

The rationale behind such invective is clear. Through such verbal provocations, Kiev hopes to extract additional economic investment from its European and American “patrons” and, more importantly, to provide military support for the regime.

Kiev has few real opportunities to play the nuclear card. Given the lack of its own uranium enrichment capacity, the “plutonium route” to nuclear weapons appears more tempting for Ukraine. The country’s spent nuclear fuel does contain approximately 7.4 tons of reactor-grade plutonium. However, Ukraine lacks industrial-scale capacity for its separation, and developing it would realistically require at least two to three years and several billion US dollars.

The situation with delivery vehicles is slightly better. Specifically, Flamingo cruise missiles could be used to deliver a potential nuclear warhead (but their actual deployment status is still unclear).

At the same time, from the perspective of our country’s interests, any flirtation with the topic of nuclear weapons by a state that poses an acute threat to us and has become a springboard for waging a hybrid war against Russia is unacceptable. In this context, any research infrastructure potentially suitable for creating a “Ukrainian bomb” must be destroyed in a Special Military Operation. The previous strikes (presumably) on the Kharkov Institute of Physics and Technology, where, according to RIA Novosti News Agency, potential weapons-grade research was underway, confirm Russia’s determination to act preemptively.

Australia: the Controversial AUKUS Factor[8]

Given Australia’s lack of domestic uranium enrichment capacity, nuclear power plants, and, consequently, spent nuclear fuel reprocessing facilities, the prospects for launching an Australian military nuclear program are slim. Given the completed AUKUS review in the United States, it seems entirely possible that the program could reach a point of no return within the next few years.

Clearly, transferring large quantities of highly enriched uranium to a non-nuclear state poses a serious challenge to the nonproliferation regime. The missile component of the partnership is already fueling an arms race in the Asia-Pacific region. However, the project’s main impact is ideological. In the future, the practice of transferring nuclear submarines could be replicated in other states with impeccable nonproliferation records, such as Japan or South Korea. Given their more developed nuclear fuel cycle infrastructure and potential loopholes in the verification regime, it cannot be ruled out that the deployment of nuclear submarines in these countries will be a prelude to nuclear proliferation.

Germany: Choosing a Trajectory

The start of the Russian Armed Forces’ Special Military Operation in Ukraine came as a shock to the German military-political elite and led to a fundamental change (Zettenweide) in Germany’s defense policy. The following points deserve attention in the long term.

It’s clear that, over the next five to ten years, pacifist and anti-nuclear sentiments in German society will be leveled out. While, since the late 2000s, approximately half of Germans favored the removal of American nuclear weapons from German soil, now approximately half of respondents in Germany support maintaining and even deepening cooperation with Washington in this area. Former Chancellor Olaf Scholz’s decision to purchase American F-35A aircraft cements Berlin’s participation in NATO nuclear missions.

With the second Trump administration, discussions have resumed in German politics about a contingency plan, should Washington at some point decide to abandon the European theater of operations. Among the options discussed are developing its own nuclear weapons or participating in a collective European nuclear deterrent force based on the French and, possibly, British nuclear arsenals.

Regarding an independent military-applied nuclear program, Berlin currently views such a scenario as purely hypothetical. It appears that the German leadership, partly due to the conservatism of German strategic culture, will delay such a decision until the last minute. Moreover, despite Germany’s considerable technical potential (in particular, it has a uranium enrichment plant), the comprehensive weaponization work will require some time. However, given its developed technical infrastructure, the availability of a powerful supercomputer base for calculating and theoretically justifying nuclear weapons, and the country’s own production of high-performance conventional explosives, there is no doubt that this work will be implemented relatively quickly if a political decision is made.

Regarding Eurodeterrence, judging by expert publications from French think tanks and statements by Emmanuel Macron, Paris is only prepared for a conceptual discussion of the role of French nuclear weapons in ensuring European security. For the current French leadership, this is a PR opportunity and a way to highlight its role in ensuring European strategic autonomy. In reality, however, the French arsenal lacks the flexibility of the American forces and assets deployed in NATO’s joint nuclear missions.

It appears that the American leadership may respond to the concerns of its European satellites and deploy more non-nuclear weapons in the European theater of operations. In a worst-case scenario, this could entail the creation of infrastructure for nuclear missions on NATO’s Eastern European border (in Poland, the Czech Republic, and the Baltic states), or even the direct involvement of these countries in nuclear weapons. From a Russian perspective, this is a casus belli requiring a decisive and, possibly, preemptive response.

Saudi Arabia: Ambiguous Ambitions

Despite having built a certain scientific, technical, and human resource base, Saudi Arabia’s starting position is far from sufficient for developing a military-grade nuclear program. Previous speculation about a secret nuclear project has either been deemed unfounded (due to objective discrepancies between defectors’ statements and reality) or requires further verification.

There’s also no political decision from the Saudi elites (which, moreover, must be synchronized with the position of the theological community – at least at the level of conducting the necessary “ideological preparation” involving the Kingdom’s spiritual authorities). The scare mongering of recent years about symmetrical steps in the event of Iran acquiring nuclear weapons has become depersonalized[9] and is rarely raised in official discourse. There are also no signs of public opinion preparing for unpopular and escalatory steps. There are also no attempts (except for statements by unnamed courtiers to the foreign press) to emphasize that the defense pact with Pakistan has a clear nuclear basis[10].

To verify the veracity of information, you can use an eight-question algorithm:

1. Who is the author of the content?

2. What precisely did you discover? Is it a thorough description, a validated idea, a succinct analysis, or only a theoretical presentation?

3. Where was the outcome discovered? What sort of resource is it?

4. Is there a link to it?

5. Who contributed to the creation of this data? Where is the server hosted, and who owns it?

6. Why was this content produced and made available online?

7. How was the content produced? Was it a fake created in less than a day, or was it the product of years of research?

8. When was the resource that held this data developed, published, and updated?

“Methodology and Practice of Open-Source Intelligence (OSINT) for

International Security, Arms Control, and WMD Nonproliferation Studies”, 2025

https://pircenter.org/editions/methodology-osint/

Modern Saudi nuclear policy is based on a sober analysis of the benefits and costs of a hypothetical nuclear arsenal. The negatives far outweigh the potential benefits. Furthermore, thanks to active international cooperation and developing military contacts with the US and China, Riyadh has no need to acquire additional tools to defend its national interests beyond those already available.

Saudi elites continue to emphasize peaceful nuclear energy as an indicator of the Kingdom’s prosperity and accelerated transformation. Switching to a military approach before achieving a certain level of peaceful nuclear energy risks cutting off access to advanced technologies, which would push Riyadh back into the race among Arabian monarchies to become the leading power in the Gulf. The minimum goal for Riyadh is to bring its national nuclear program up to the level of the UAE, and the maximum is to elevate it to the level of Iran. However, for now, the Saudis are focused only on the first stage.

Of course, it’s possible that Saudi Arabia would be interested in maintaining uncertainty about its actual capabilities and intentions; it would continue to monitor the Iranian nuclear project and respond to any negative developments (from Riyadh’s perspective). However, even in this case, the prospect of Saudi Arabia acquiring its own nuclear arsenal can currently be assessed as unlikely.

Türkiye: a Strategy of “Cautious Populism”

Despite the Turkish elite’s periodic attempts to probe public opinion on the issue of acquiring a nuclear arsenal[11], Türkiye is still technologically far from being able to independently launch a military nuclear project.

The country has a good starting position, but its technological potential remains underdeveloped: the most sensitive elements of the nuclear fuel cycle – uranium enrichment and spent nuclear fuel reprocessing – are missing. Given the current IAEA Additional Protocol, it is highly unlikely that Ankara has the capacity to create such infrastructure undetected. Furthermore, the delivery vehicle development program is only just gaining momentum—current resources are insufficient, and ambitious IRBM projects are still at the prototype stage, preventing Ankara from quickly consolidating its achievements and stockpiling a sufficient number of warheads before the punitive measures are activated.

Diplomatic restraints are also effective. For example, the potential military conversion of Ankara’s nuclear ambitions is guaranteed to deepen Ankara’s rifts with its neighbours, provoking not only estrangement in relations with the US and EU countries but also exacerbating the conflict with Israel. Israeli hawks led by Benjamin Netanyahu will not allow the emergence of another nuclear-armed power in the Middle East (even one de facto not hostile to it) and, to maintain the balance of power, will not hesitate to sacrifice trade and economic cooperation with Türkiye.

However, even in the face of a forceful response from Israel, Türkiye, having decided to pursue its own nuclear arsenal, would almost certainly find itself in diplomatic and economic isolation. Given its heavy dependence on foreign trade and the instability of the country’s financial system, this would guarantee a sharp decline in living standards and a surge in social tensions. Recep Erdoğan’s government is clearly unwilling to take such risks.

On the other hand, Erdoğan hasn’t forgotten about nuclear populism. He also notes the gradually emerging demand in Turkish society for an effective deterrent against Israel and other regional adversaries[12].

For now, this issue has been mitigated by shifting the focus to hypersonic weapons. However, nuclear arsenals appear more deadly and threatening to the public. This means Ankara will sooner or later be forced to revisit the topic. However, even then, the nuclear weapons issue will be used more as a platform for attracting voters than as an area where the country intends to take real escalatory steps.

Iran: A Controversial Dossier

Among the potential “nuclear newcomers”, Iran remains the player most hotly debated. Estimates of the time Iran would need to develop warheads, prevalent among experts (especially Western ones), are generally oversimplified and range from three months to a year and a half, periodically shifting upward or downward to suit political expediency. Moreover, such time estimates are typically based on mathematical modeling of centrifuge efficiency and do not take into account the subsequent work of so-called weaponization.

Iranian capabilities are estimated solely on the basis of open data, which, given the closure of Iranian production facilities from prying eyes, increases the margin of error. At the same time, researchers from various schools of thought generally agree: despite some damage inflicted on Iran during the standoff with Israel (and the US and several European countries that supported it), Tehran still possesses the technical potential sufficient to create nuclear weapons. While continuing to adhere to the symbolic self-restraints that have been taken upon themselves.

The prospect of resuming the previously closed Amad project (or even accelerating it) under current conditions appears extremely dim, due both to gaps in the work of Iranian scientists at the time (and the objective obsolescence of some data and technologies), and to Tehran’s loss of some of its unique knowledge holders. Furthermore, despite a relatively high level of scientific and technological development (as well as the gradual “closure” of the Iranian nuclear sector from prying eyes after the collapse of the JCPOA in 2018), Tehran has still not resolved the issue of protecting key scientists – a resource that is much more difficult to restore than technical infrastructure. Furthermore, the possibility of completely moving work on the nuclear project underground is also questionable, given the active attention of foreign intelligence agencies (not only those of unfriendly states) to this area of Iranian scientific work.

The data available to date remains insufficient to conclude with a high degree of certainty that the authorities have made a political decision to abandon the exclusively peaceful nature of the nuclear program. The upheavals surrounding the JCPOA, Iran’s reduction of its commitments under the deal, and the final escalation of the conflict with Israel into an existential standoff continue to blur the line between signs of peace enforcement and the initiation of a military nuclear program. Clearly, opposition to IAEA inspection activities is consistent with the logic of a response to US actions, and the strengthening of measures to protect nuclear physicists is driven by the risk of sabotage.

There are no signs of public sentiment being whipped up in favor of the nuclear option to justify the growing economic difficulties in the eyes of the population (although the issue is being probed in both directions – toward escalation and a new “deal” with the West). There is no reliable information about the creation of any superstructures empowered to coordinate the military-applied nuclear program.

Israel: Double Uncertainty Continues

Israel retains its informal status as the Middle East’s “only nuclear power” – although it does not officially confirm (but also does not deny) the existence of a nuclear triad (the so-called Amimut concept).

Within the country (and within the global Jewish community as a whole), its future remains a subject of ongoing debate. At various times, Israeli military and civilian officials, as well as members of the scientific community, have opposed Amimut, believing that public self-restraint hinders the development of national nuclear science and the military-industrial complex and creates leverage for external pressure (primarily in the interests of the United States)[13]. However, the number of supporters of maintaining this “double uncertainty” still far outweighs those opposed. Even the most ardent skeptics acknowledge that Amimut, despite its ambiguity, is an effective tool for curbing the ambitions of Arab countries and Türkiye. The latter allegedly hesitate to use conventional weapons against Israel for fear of facing “an exponentially greater response”. Meanwhile, Amimut has been less effective against Iran in recent years, but other restraints available to Tel Aviv come into play here.

The most interesting results usually come from comparative analysis of images of the same object taken at different times, looking for changes. Look for changes in the terrain, land clearing, buildings, or roads. Sometimes, changes in the terrain are obvious. In other cases, it’s impossible to clearly determine from satellite images whether a building has actually been constructed or whether construction is still underway. In this case, careful observation of shadows can help. If a tall building or object is under construction, a shadow will appear in the image, which can be used to determine the degree of development and even the time and distance.

“Methodology and Practice of Open-Source Intelligence (OSINT) for

International Security, Arms Control, and WMD Nonproliferation Studies”, 2025

https://pircenter.org/editions/methodology-osint/

The balance of power and the tone of assessments are also influenced by the political climate. Israeli society has been tilting to the right for several years now, accelerating after the escalation of tensions in the Gaza Strip (i.e., since October 2023). The authorities’ tendency to portray Israel as a besieged fortress creates a predisposed negative attitude toward its neighbours and regional opponents.

At the same time, political forces in Israel are fragmented – there is no absolute consensus either within the opposition camp or in the ruling coalition; certain figures (mostly former high-ranking security officials) prefer to keep their distance, attempting to independently form a “third force”. It is important to understand, however, that a fully formed and accepted anti-nuclear force currently does not exist in Israel. Both the ruling and opposition camps do not support further adherence to the principle of nuclear ambiguity or the deliberate overstatement of their own capabilities in order to deter and intimidate opponents. The only difference is that the right-winged fractions, led by Netanyahu, intends to continue raising the stakes in the conflict with Iran, hinting at inevitable new clashes “until the nuclear threat is completely eliminated”, while the opposition allows for the possibility of a minor “détente” with Tehran and forces loyal to it – at least until the level of 2021–2022. Supporters of nuclear transparency, however, are generally disunited; They belong to small-scale (usually left-wing) parties and organizations and have a relatively low chance of crossing the electoral threshold for the Knesset. Furthermore, anti-nuclear rhetoric is not the main focus of their speeches and has recently been almost completely replaced by Palestinian themes.

Overall, it’s unlikely to see any fundamental changes in Israel’s nuclear policy in the foreseeable future – it will continue to be based on the same principles as before. At the same time, Tel Aviv is almost guaranteed to begin increasing its intelligence and subversive activities against Iran in order to more effectively and promptly prevent potential nuclear weapons development.

Conclusion

The emergence of new nuclear states on the world political map remains unlikely – most players that have approached “threshold status” on one track or another still lack the comprehensive capability to convert their nuclear programs to military use.

Moreover, existing restraining factors – the continued stability of the NPT as an international norm, the vulnerability of potential troublemakers to economic sanctions, and the high cost of full-fledged nuclear programs and the development of delivery systems – are currently sufficient to keep these states on the brink of collapse. There are clearly no plans to expand the Nuclear Club or open a “newcomers’ section” within it.

However, it’s not worth making any final decisions here, nor should we fall prey to false complacency. The US’s excessive indulgence of several nuclear aspirants (Australia and South Korea), Japan’s revanchism, which is acquiring nuclear overtones, and Ukraine’s ongoing attempts to turn the nuclear weapons issue into a bargaining chip in negotiations and thereby compensate for setbacks on the battlefield – all of this is creating dangerous turbulence and undermining confidence in the sustainability of the international nonproliferation regime in its current form.

Russia – as a superpower and one of the depositaries of the NPT – should constantly focus on the small nuclear steps taken by other players, combat double standards, and build a new security architecture with minimal dividing lines. This is one of the key ideas enshrined in the Greater Eurasia security concept, and it can (and should) be applied to nuclear nonproliferation. Otherwise, carelessness and overconfidence in the NPT’s steadfastness could backfire in the near future.

And not just on us.

[1] Nomina sunt odiosa – is a Latin phrase that translates to “names are hateful” and is used when avoiding direct blame or criticism. It suggests that naming individuals in a reproachful situation is unpleasant or distasteful, and it is often used to avoid making the criticism personal or specific. – Editor’s note.

[2] In shift, South Korea’s top diplomat says nuclear armament ‘not off the table’ // NK News. February 27, 2025. URL: https://www.nknews.org/2025/02/in-shift-south-koreas-top-diplomat-says-nuclear-armament-not-off-the-table/

[3] 123 Agreements // US Dept. of State. URL: https://www.state.gov/bureau-of-international-security-and-nonproliferation/releases/2025/01/123-agreements

[4] See e.g.: What is South Korea’s ‘monster missile’, and what does it mean for relations with the North? // the Guardian. October 23, 2025. URL: https://www.theguardian.com/world/2025/oct/23/south-korea-monster-missile-hyunmoo-5-balance-power-north

[5] Sample size: 1200 people. See: Almost 70% of respondents believe a world without war will never become a reality. About half of respondents believe Japan is currently at peace, but they also express concern about the future // Red Cross Japan. July 29, 2025. URL: https://www.jrc.or.jp/press/2025/0729_048166.html (in Jap.)

[6] Atomic Bomb Awareness Survey (Hiroshima, Nagasaki, and Nationwide) Simple Count Results. URL: https://www.nhk.or.jp/bunken/research/yoron/pdf/20150805_1.pdf (in Jap.)

[7] Japanese Public Opinion, Political Persuasion, and the Treaty on the Prohibition of Nuclear Weapons // Belfer Center. URL: http://belfercenter.org/publication/japanese-public-opinion-political-persuasion-and-treaty-prohibition-nuclear-weapons

[8] For more information on the topic, see Chapter 17 of this Yearbook – Editor’s note.

[9] Saudi prince warns of ‘war with the entire world’ in the event of a nuclear strike // Russian Gazette. September 21, 2023. URL: https://rg.ru/2023/09/21/saudovskij-princ-predupredil-o-vojne-so-vsem-mirom-v-sluchae-iadernogo-udara.html (in Russ.).

[10] Saudi Arabia, nuclear-armed Pakistan sign mutual defence pact // Reuters. September 17, 2025. URL: https://www.reuters.com/world/asia-pacific/saudi-arabia-nuclear-armed-pakistan-sign-mutual-defence-pact-2025-09-17/

[11] See e.g..: How can we prevent this evil purpose? // Yeni Safak. URL: https://www.yenisafak.com/yazarlar/hayreddin-karaman/bu-melun-amaci-nasil-engelleriz-4643524 (in Turkish); Fatwas as Tools of Religious Populism: The Case of Turkish Islamist Scholar Hayrettin Karaman // European Center of Populism Studies. September 1, 2024. URL: https://www.populismstudies.org/fatwas-as-tools-of-religious-populism-the-case-of-turkish-islamist-scholar-hayrettin-karaman/

[12] Most Turkish people say Turkey should obtain nuclear weapons in new poll // Middle East Eye. July 17, 2025. URL: https://www.middleeasteye.net/news/most-turks-say-turkey-should-obtain-nuclear-weapons-poll

[13] Cohen A. The Worst-Kept Secret. Israel’s Bargain with the Bomb // Columbia University Press. URL: http://cup.columbia.edu/book/978-0-231-13698-3/the-worstkept-secret