It was in 1957 when the only and the first artificially created object – the Soviet-made sputnik with the weight of 84 kg and 54 cm in diameter – entered outer space. Since then, after more than 60 years, outer space is almost overcrowded with thousands of artificial objects: huge manned orbital stations and microsatellites, inter-planet vehicles and others. The use of outer space has significantly increased over previous 20-30 years. Its benefits are obvious in all economic, military, and civilian fields. Space technologies are indispensable to scientific research, Earth monitoring, arms control. They provide us with stable cell phone communications, TV and radio broadcasting, the Internet, road and sea navigation, weather forecasts, even with tracking our pets. As a result, outer space has transformed into a huge, multifunctional, interconnected global and borderless infrastructure.

But how does it coexist with military activities in outer space? Does the militarization of outer space pose a threat or a challenge to its peaceful uses? Can they coexist, or their confrontation is inevitable? What diplomatic and legal steps are needed to be made to avoid the relocation of arms race to outer space? To answer these relevant questions, it would be important to make an overview of major tendencies in the development of the civilian outer space network and its challenges it faces.

Scaling up and diversification of outer space exploration

“In the past 10 years, humanity’s access to and operations in outer space have fundamentally changed and the driving factors behind these changes are likely to accelerate in the coming decades. Of the many indicators that show evidence of this unprecedented change, three stand out: the number of objects launched to orbit; the participation of the private sector; and commitments of public and private actors to return to deep space and enable the long-term presence of humanity among the celestial bodies. This revolutionary change, like other twenty-first century technology-enabled breakthroughs, presents us with both opportunities and risks, and we need to develop further the existing governance so that we can sustainably accelerate innovation and discovery with a view to achieving the Sustainable Development Goals”.

Our Common Agenda Policy Brief 7

For All Humanity – the Future of Outer Space Governance

May 2023

Source: United Nation

(https://www.unoosa.org/res/oosadoc/data/documents/2023/a77/a77crp_1add_6_0_html/our-common-agenda-policy-brief-outer-space-en.pdf)

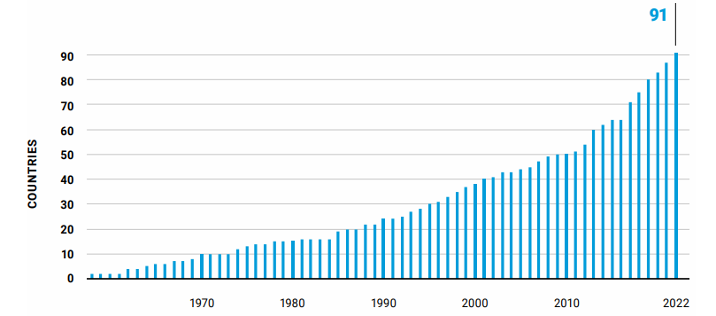

The intensification of outer space activities could be illustrated by the following statistics and facts. The Committee on the Peaceful Uses of Outer Space (COPUOS) which was set up by the United Nations General Assembly in 1959 as a principal international body to govern the exploration and use of outer space for peace, security, and development, consists now of 102 member states[1]. The 65th session of COPUOS, which took place in 2022, was attended by representatives from 87 states as well as five other UN entities, eight intergovernmental and 14 nongovernmental organizations [2]. According to the UN there are 91 countries which own at least one satellite[3]. It leads us to the conclusion that 90-100 countries have a real interest in outer space exploration. More than 500 people from 30 countries have visited outer space as cosmonauts, astronauts, or taikonauts.

Initially, space activity was exclusively within the realms of states. In the early 1960s, only the Soviet Union and the United States dominated this area. It was very costly to build and operate outer space infrastructure: launch facilities, rockets, and satellites. Now, as the leading Russian legal expert on outer space Yuri Kolosov has put, private capital literally bursts into outer space, bringing it closer to the practical individual needs and at the same time creating new legal problems[4]. As a result, outer space has become the domain of private business and public entities such as international organizations, universities, and others.

Thousands of private structures are working in outer space industry. Commercial revenues exceed government spending. As it was noted at the meeting of the Security Council of the Russian Federation in 2019, the size of the global market in outer space commercial services is about 183 billion dollars per year, and it will increase in the coming years and decades[5]. In 2022, experts indicated that the global space market had grown by 8 percent to 424 billion dollars and was expected to reach more than 737 billion dollars by 2030[6]. Similar estimates were made by the Space Foundation, a nonprofit organization which expected the global outer space economy to be 469 billion dollars worth in 2021[7].

Main segments of the global outer space market include ground infrastructure facilities, space rockets, satellites, communication systems, Earth observation means. An outer space insurance market has emerged. Outer space tourism and even space cinematography have become routine. At the same time, private business is not able to operate and maintain national outer space programs on its own without organizational and financial support from the state.

Steep rise in frequency of outer space launches leads to the density in orbits

A huge number of satellites and other objects have been launched into outer space. In 1962, the United Nations established a Register of Objects Launched into Outer Space. It is instrumental in identifying which state bears international responsibility and liability for space objects in case of an accident. This mechanism is detailed in the 1974 Convention on Registration of Objects Launched into Outer Space. According to the Article II (1), “When a space object is launched into Earth orbit or beyond, the launching State shall register the space object by means of an entry in an appropriate registry which it shall maintain. Each launching State shall inform the Secretary General of the United Nations of the establishment of such a registry”. The Secretary General in return shall maintain the UN Register[8].

As of April 1, 2023, there were about 10.290 satellites in the Earth’s orbit, nearly 7.800 are operational and the rate of launches is constantly increasing[9]. From 1957 to 2012, the number of satellites launched into outer space remained remarkably constant at approximately 150 each year[10]. However, after that the number of satellites launched into orbit began to grow exponentially, from 210 in 2013 to 600 in 2019, to 1.200 in 2020 and most recently to 2.470 in 2022[11]. This rise became possible due to the emergence of a new technological trend to launch small, micro- and nano-satellites. The first satellite weighed 84 kg; the International Space Station (ISS) weighs 420 tons. Now thousands of increasingly tiny, small satellites such as micro- and nano-satellites weighing 1 kg or less are created. One rocket is capable of launching hundreds of such satellites.

Private entities, universities and even schools are involved in the massive production of small satellites. It results in the tenfold increase in the number of satellites registered in the UN Register. As of today, governments have registered radio frequencies with the International Telecommunications Union (ITU) for more than 1.7 million non-geostationary satellites that may be launched into orbit by 2030[12]. The UN argues that there is “a proliferation of new constellations of small satellites”[13].

Consequently, mankind becomes increasingly dependent on outer space satellite technologies. However, it leads to the growing congestion in the orbital space. Satellite orbits and radio frequencies cannot expand indefinitely. Geostationary orbit is already the most overcrowded: two-thirds of all satellites are located there, and their number is growing rapidly. The use of radio frequencies is increasing. As a result, there are disputes and concerns about radio interference and orbital crowding. And it is not by chance that the Legal Subcommittee of the COPUOS began to consider rational and equitable use of the geostationary orbit. It was also recommended to consider a legal regime for low orbits.

Debris as an outer space challenge

Multiplying number of space objects has created a new problem – space debris. According to the report by the UN Office for Outer Space Affairs (UNOOSA), over 31.000 near Earth objects have been discovered including 2.000 objects classified as potentially hazardous[14]. It is a real threat to sustainability of outer space operations. There are more than 24.000 objects 10 cm in size or larger, one million smaller than 10 cm, and likely more than 130 million smaller than 1 cm in size. Objects as small as a chip of paint, travelling at more than 28.000 km per hour, can cause significant damage to any spacecraft[15].

The ISS has been more than once bombarded by fast-moving debris. Some researchers claim that we are already on the brink of the Kessler Syndrome. It is about the scenario of cascading collisions of debris in the geometric progression in low earth orbits[16]. Such a pollution could make the nearest outer space unusable. Solutions to the problem are complicated due to huge financial, technical, and intellectual costs. They should include measures to prevent the multiplication of debris, to clean up orbital space and to protect orbital systems from damage and destruction.

This issue is on the top of the COPUOS agenda. It has adopted the Space Debris Mitigation Guidelines which were endorsed by the UN General Assembly in its Resolution 62/217 in 2007[17]. But this document is only a set of general principles recommended to national outer space bodies. Neither a legally binding convention nor an international mechanism have been adopted so far to monitor outer space debris or facilitate their removal.

Challenges to long-term outer space sustainability

One of the challenges is the lack of progress in the COPUOS discussions on the outer space traffic management. There are no agreed or clear rules or protocols which regulate movement, maneuvers, and disposition of satellites in orbits. In 2019, COPUOS adopted a set of Guidelines for the Long-Term Sustainability of Outer Space Activities. They provide guidance on the safety of outer space operations; international cooperation, capacity-building, awareness; scientific and technical research and development. However, the Guidelines are purely advisory and incomplete. It was decided to continue to work on the long-term sustainability[18].

To sum up: total dependence of mankind on outer space technologies and the density in outer space attest to its fragility and the need to maintain it in a balanced, safe, and secure order. Any confrontation and upset this balance could result in the collapse of the global economic and social life.

Militarization vs weaponization of outer space

What about military activities in outer space? Do they pose a threat or a challenge to outer space environment? First and foremost, it should be emphasized that outer space is the only domain, unlike airspace or oceans, with no deployed weapons. Outer space is militarized but, luckily, not weaponized. Outer space is full of military satellites, but they do not operate as weapons. They serve as eyes and ears to perform informational functions.

Among legally permitted military activities are:

- use of surveillance satellites and space-based remote sensors to monitor compliance with arms control and disarmament treaties;

- use of outer space communication, navigation and meteorological support systems;

- use of unarmed military personnel at manned spacecraft and celestial bodies to conduct scientific research.

Moreover, the use of military outer space devices is expanding for such civilian purposes as monitoring natural and man-made disasters. So far, both above trends in outer space exploration – peaceful and military-informative – have been developing in parallel, without conflicts. But for how long? If weapons do appear in outer space, these trends will certainly come into conflict. The advance of cutting-edge military technologies has reached the point when outer space systems with combat attack capabilities can be deployed in the foreseeable future.

US National security strategies and doctrines describe outer space as a warfare domain. According to the US Space Forces Command Report released in 2022, “the US may undertake offensive operations within the bounds of US domestic laws and policy, and international law to negate an adversary’s use of military or hostile space capabilities…”[19]. Such operations “may include actions to deceive, disrupt, deny, degrade, or destroy the adversary’s military outer space capabilities”[20]. As the UN warns, “an armed conflict that extends into outer space would significantly increase the potential for space debris and the compromising the safety of critical civilian infrastructure, disrupting communications, observation and navigation capabilities that are vital to the global supply chain”[21].

Legal restrictions on military outer space activities

The international law has imposed certain restrictions on military uses of outer space.

1963 Treaty Banning Nuclear Weapon Tests in the Atmosphere, in Outer Space and Under Water, or Limited Test Ban Treaty (LTBT), prohibited nuclear tests in all spheres except underground. As its Article I (1) says: “Each of the Parties to this Treaty undertakes to prohibit, to prevent, and not to carry out any nuclear weapon test explosion…in the atmosphere; beyond its limits, including outer space…”[22]. It has come along as the first treaty to specifically prohibit certain military activities in outer space.

The 1967 Treaty on Principles Governing the Activities of States in the Exploration and Use of Outer Space, Including the Moon and Other Celestial Bodies (Outer Space Treaty, or OST), became “the cornerstone of the international legal regime governing outer space”[23]. The Treaty placed specific prohibitions on concrete military activities. Its Article IV obliges the states parties “not to place in orbit around the Earth any objects carrying nuclear weapons or any other kinds of weapons of mass destruction, install such weapons on celestial bodies, or station such weapons in outer space in any other manner. The Moon and other celestial bodies shall be used by all States Parties to the Treaty exclusively for peaceful purposes. The establishment of military bases, installations and fortifications, the testing of any type of weapons and the conduct of military maneuvers on celestial bodies shall be forbidden”[24].

Close reading of these provisions makes it clear that celestial bodies, including the Moon, shall be permanently and completely demilitarized. In contrast, open outer space with its orbit around the Earth shall be free from selected types of weapons only, i.e., “nuclear weapons or any other kinds of weapons of mass destruction”[25]. In the opinion of Yuri Kolosov and Sergey Stashevsky, the overwhelming majority of lawyers, when interpreting Article IV of the Outer Space Treaty, proceed from the fact that the regime of complete demilitarization has been established in relation to the Moon and other celestial bodies, whereas in relation to outer space itself it is the regime of partial demilitarization[26].

The range of prohibited military activities was expanded in the 1979 Agreement Governing the Activities of States on the Moon and Other Celestial Bodie (Moon Agreement). It came into force in 1984 but has only 13 ratifications with no participation of states with a significant outer space potential. If viewed as a legal option, its obligations are expanded in comparison to the Outer Space Treaty. It specifically urges not to place in orbit or around the Moon objects carrying nuclear weapons or any other kinds of weapons of mass destruction. The Agreement also prohibited any threat or use of force or any other hostile act or threat of hostile act on the Moon[27].

1972 Anti-Ballistic Missile Treaty (ABM Treaty) concluded by the US and the USSR prohibited for the both countries to develop, test, or deploy anti-ballistic missiles systems or components which are sea-based, air-based, space-based[28]. The Treaty had been in force for 30 years until 2002 when the US decided to withdraw from it, and that resulted in its termination. In spite of it, the USA and Russia continue to honor the commitment not to deploy anti-ballistic missiles in outer space.

With all its significance, international law imposes only selected bans and limitations on the deployment and use of weapons in outer space. Lack of definitions, incompleteness of prohibitions and their scope have exposed many legal lacunas and gray areas in that domain. Some experts distinguish the following weapons-related activities in outer space which are not regulated by international law: testing and deployment of anti-satellite weapons (ASAT); deployment of conventional attack weapons and weapons based on new physical principles that cannot be classified as weapons of mass destruction; deployment of weapons designed to attack targets on Earth; deployment of optical or radio-electronic suppression means, etc. Since the times of Ronald Reagan’s (1981-1989) Star Wars Strategic Defense Initiative, several combat attack systems have been under development, particularly anti-satellite kinetic weapons, Earth- or space-based lasers, electromagnetic guns, other directed energy weapons, etc.[29]. Anti-satellite weapons were tested by the USA, China, India, and Russia. Once deployed by one state they will inevitably provoke others to restore the upset military balance and thus will launch an inevitable arms race in outer space.

Diplomatic efforts to prevent weaponization and arms race in outer space

Russia, China, and many other states are taking persistent diplomatic efforts to prevent weaponization of outer space. They are above all aimed at the promotion of several UN General Assembly resolutions. Below are several resolutions adopted at the 77th Session of the General Assembly in 2022/2023[30]. This is a set of resolutions adopted by consensus, i.e., without voting, which contain general recommendations.

- Resolution 77/40 Prevention of an Arms Race in Outer Space (PAROS) concludes that “the legal regime applicable to outer space by itself does not guarantee the prevention of an arms race in outer space” and reaffirms “the importance and urgency of preventing an arms race in outer space and the readiness of all States to contribute to that common objective”[31].

- Resolution 77/251 Transparency and Confidence-Building Measures in Outer Space Activities supports non-military uses of outer space. It is based on the corresponding Report of the Group of Governmental Experts prepared in 2013. The Resolution stresses the importance of that Report and “encourages Member States to continue to review and implement, to the greatest extent practicable, the proposed transparency and confidence-building measures contained in the Report”[32].

- Resolution 77/121 International Cooperation in the Peaceful Uses of Outer Space is an apparent alternative to outer space confrontation. It reiterates the need “to promote the benefits of space technology and its applications at the major United Nations conferences and summits for economic, social and cultural development and related fields”, and recognizes that the “fundamental significance of space science and technology and their applications for global, regional, national and local sustainable development processes should be promoted, including… in implementing the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development”[33].

- Resolution 77/120 Space and Global Health encourages peaceful “international cooperation in the field of space medicine on the basis of equal opportunities for all interested participants”[34]. However, when it comes to practical steps regarding prevention of arms race in outer space, Russian initiatives are opposed by the USA and their allies voting against.

- Resolution 77/42 No First Placement of Weapons in Outer Space was initiated by Russia as a first step and a provisional measure until the adoption of a legally binding treaty on the non-placement of weapons in outer space. It “encourages all States, especially space faring nations, to consider the possibility of upholding, as appropriate, a political commitment not to be the first to place weapons in outer space”[35] (122 voted in favor, 50 – against (almost all – USA and their allies), 4 – abstained). Apart from that Resolution, more than 30 countries followed Russia’s voluntary and unilateral commitment not to be the first to place weapons in outer space. Russian Foreign Ministry argues that such a commitment “is the highest form of interstate transparency and mutual trust and thus it is currently the most effective and actually working measure to prevent the launch of weapons to outer space”[36].

- Resolution 77/250 Further Practical Measures for the Prevention of an Arms Race in Outer Space declares that the “exclusion of outer space from the sphere of arms race and the preservation of outer space for peaceful purposes should become a mandatory norm of state policy and a generally recognized international obligation”[37]. It “urges the Conference on Disarmament to agree on and to implement…a balanced and comprehensive program of work that includes immediate commencement of negotiations on an international legally binding instrument on the prevention of an arms race in outer space, including on the prevention of the placement of weapons in outer space and of the threat or use of force in outer space, from space against Earth and from Earth against objects in outer space”[38]. It also requests the Secretary General to reestablish a UN Group of Governmental Experts to consider and make recommendations on substantial elements of an international legally binding instrument on the prevention of an arms race in outer space. Such a group was preparing a report on basic elements on such a legal instrument in 2017-2019, but its consensus adoption was blocked by the USA without any explanations (115 voted in favor of the Resolution, 47 – against, 7 – abstained).

With all the merits of the UN resolutions, it should be understood that they contain only general appeals and recommendations and cannot by themselves generate practical steps and initiate official talks. However, in the absence of political will they add up to a valuable public and political thrust towards future practical actions and legal arrangements.

The main focus of Russia’s diplomatic efforts is the promotion of the draft Treaty on the Prevention of Placement of Weapons in Outer Space, the Threat or Use of Force against Outer Space Objects (PPWT). In 2008, Russia and China presented at the Conference on Disarmament in Geneva a draft with elements of such a treaty, and in 2014 both sponsors updated the version, with taking into account the comments they received after the discussion[39]. In developing this document its authors worked proactively. They proceeded from the fact that it was much easier and more effective to prevent the placement of weapons in outer space than to negotiate it when the arms race had already begun. The draft treaty eliminates legal gaps in the current 1967 Outer Space Treaty. For example, a detailed definition of the term weapon in outer space is provided. The authors prudently avoided categorizing the types of possible weapons. Evidence from experience suggests that it is impossible to give a legally comprehensive universal description of each weapon. Future new weapons could neither be foreseen nor included in such a list. To avoid this trouble the draft focuses on the functions of weapons placed in outer space. According to Article I (b), such a weapon “means any outer space object or component thereof which has been produced or converted to destroy, damage or disrupt the normal functioning of objects in outer space, on the Earth’s surface or in its atmosphere, or to eliminate human beings or components of the biosphere which are important to human existence, or to inflict damage on them by using any principles of physics”[40]. The terms use of force or threat of force have been clarified. In Article I (d), the term use of force means any action intended to inflict damage on an outer space object under the jurisdiction and/or control of other states, and the term threat of force means the clear expression in written, oral or any other forms of the intention to commit such an action[41].

The obligations of the states parties to the draft PPWT are the following:

- not to place any weapons in outer space;

- not to resort to the threat or use of force against outer space objects of states parties to the treaty;

- not to engage, as part of international cooperation, in outer space activities that are inconsistent with the object and purpose of this treaty;

- not to assist or induce other states, groups of states, international, intergovernmental or nongovernmental organizations, including nongovernmental legal entities established, registered or located in territory under their jurisdiction and/or their control, to participate in activities inconsistent with the object and purpose of this treaty.

Source: Conference on Disarmament.

(https://cms.spacesecurityportal.org/uploads/DPROK_anglijskij_2014_e2530346b0.pdf)

The draft PPWT is being discussed at the Conference on Disarmament in Geneva, but without a negotiating mandate. The problem is that all negotiation tracks in the Conference on Disarmament since 1998 have been blocked because of disagreements on the agenda issues. The United States and their allies are opposed to negotiations on PPWT in any format. It is clearly visible in their voting records against the corresponding UN resolutions. Lately the chances for effective diplomacy towards PAROS and PPWT have become even slimmer. The main spoilers here are the announced development in the USA of large-scale missile defense systems with space-based components; claims to dominance in outer space; plans to privatize space resources.

In the current poisoned geopolitical juncture, it would be unrealistic to expect positive developments, at least in the mid-term future. Washington and its allies will definitely confront meaningful talks on the PPWT and PAROS. Moreover, the USA and their allies sponsored two UN General Assembly resolutions which could not be regarded otherwise but as an attempt to divert attention from the PPWT. The UN General Assembly Resolution 76/231 Reducing Space Threats through Norms, Rules and Principles of Responsible Behaviors promulgates the creation of an Open-ended Working Group “to make recommendations on possible norms, rules and principles of responsible behaviors relating to threats by States to space systems”[42]. Russia, China, and some other countries voted against because the Resolution sets out dubious new concepts and approaches towards the assessment of threats. Who and on which criteria will determine what kind of behavior is right or wrong, which one state is responsible, and which is not? Is it not clear either how in the current geopolitical situation Western countries will qualify just any type of Russian or Chinese behavior? It also seems that the term behavior has nothing to do with the legal language and legal terms.

The UN General Assembly Resolution 77/41 Destructive Direct-Ascent Anti-Satellite Missile Testing calls upon all states “to commit not to conduct destructive direct-ascent anti-satellite missile tests”; it also “considers such a commitment to be an urgent, initial measure aimed at preventing damage to the outer space environment, while also contributing to the development of further measures for the prevention of an arms race in outer space”[43]. This Resolution could have been supported if it were free from essential deficiencies. Why does it select only a certain type of outer space weapons and is silent about others? Why does it not call for the start of negotiations?

The motives which stood behind this Resolution were revealed in the Joint Statement on the Initiative on Undertaking Political Commitment not to Conduct Destructive Direct-Ascent Anti-Satellite Missile Tests adopted in 2022 by Russia, China, and a couple of other states. The Statement clarifies that “the adoption of such commitment does not imply the renouncement of developing and manufacturing the said anti-satellite systems, their combat use or non-destructive ASAT tests”[44]. The elimination of the already available weapons of this type is not envisaged as well. As a result, as soon as this initiative becomes universal, the advantages for a certain group of states that are already in possession of such means will emerge, while others, primarily the developing countries, will find themselves in a discriminated position[45]. Thus, Resolution 77/41 can be characterized as a half if not a quarter remedy.

What comes next?

Still, despite the current highly volatile and unpredictable geopolitical situation it is both imperative and possible for Russia to work for the PPWT and PAROS on the following tracks:

- To continue together with China to create a critical mass in favor of the draft PPWT. To circulate among the interested states a new updated questionnaire on their assessment of the draft and on its possible improvement.

- To expand the number of countries supporting the UN GA Resolution 77/42 No First Placement of Weapons in Outer Space.

- To increase the number of countries which have personally and voluntary committed not to be the first to launch weapons to outer space. It seems that additional efforts towards such an obligation should be taken within BRICS and the Shanghai Cooperation Organization (SCO). Not all their members have pledged such a commitment.

- Promote Russia’s comprehensive PAROS program vs emasculated Western proposals. It was summarized in the commentary issued by the Russian Foreign Ministry in 2022 and envisages the following commitments:

- not to use outer space objects as a means of destroying any targets on Earth, in the air or in outer space;

- not to create, test, deploy or use outer space weapons for anti-missile defense, anti-satellite tasks, or use them against targets on Earth or in the air;

- not to destroy, damage, or disrupt normal functioning and not to change the flight paths of outer space objects owned by other states;

- not to assist or encourage other states, groups of states, international, intergovernmental, or any nongovernmental organizations and legal entities… to participate in the above activities”[46].

The last proposal is especially relevant regarding the conflict in Ukraine. Numerous reports, official and non-official revelations indicate that private satellite communication systems including those owned by Elon Musk’s Starlink satellites are widely used to target and hit Russian troops and civilian facilities in the course of Special Military Operation in Ukraine. Previously “the US military relied on private networks during the First Gulf War [1990-1991] — a tactic that has become a mainstay of conflict zones globally”[47].

Russian diplomats have already raised great concern. For instance, they have warned that “we are witnessing the fact that civil space infrastructure, primarily communication and Earth sensing satellites are increasingly used… for direct participation in armed conflicts”[48].

“An extremely dangerous trend…has become apparent… in Ukraine. Namely, the use by the United States and its allies of civilian and commercial infrastructure elements in outer space for military purposes. Those states do not fully realize that such actions in fact constitute indirect participation in military conflicts. Quasi-civilian infrastructure may become a legitimate target for a retaliatory strike”.

From the Statement of the Deputy Head of the Delegation of the Russian Federation

and Deputy Director of the Russian Foreign Ministry Department for

Nonproliferation and Arms Control Konstantin Vorontsov at the Thematic

Discussion on Outer Space in the First Committee of the 77th Session of the UN

General Assembly

October 26, 2022

Source: Russian Foreign Ministry

(https://www.mid.ru/ru/press_service/1835557/?lang=en)

It seems that, indeed, direct incursion in a civilian outer space infrastructure of one state in an armed conflict on the territory of another one might become the most likely cause for a real military clash in outer space. This new development deserves the uppermost attention. It is highly dangerous, politically, and legally unacceptable. As the first step, what is needed is a novel UN General Assembly resolution on non-use of civilian satellites and infrastructure in support of military operations in foreign armed conflicts. Subsequently it might be integrated into general legal frameworks of PAROS.

Conclusion

Outer space technologies with their revolutionary innovative achievements have penetrated almost all aspects of our economic, social, and even personal affairs. Outer space global infrastructure is expanding in immense proportions. However, the unrestricted outer space exploitation and the lack of space traffic rules have also brought about numerous challenges such as density in orbits and an expanding cloud of uncontrolled debris. Total dependence of mankind on outer space and its fragility only reaffirm the urgent need to preserve outer space as a peaceful, safe and secure domain.

Outer space is militarized but, luckily, not weaponized. However, some not legally prohibited weapon-type systems have been created and even tested and are almost about to be deployed. If and when one country stations weapons in outer space, others will immediately follow suit in an inevitable arms race. Military clash in outer space will put the whole unprotected civilian space infrastructure on the brink of complete collapse.

Russia, China, and some other states continue taking diplomatic and legal efforts to prevent arms race in outer space and to prohibit deployment of any types of space weapons. But their initiatives are being blocked by the USA and their allies. Time will show whether outer space will be preserved as the last remaining weapon-free zone, or it will slide down into an arms race. In order to avoid the worst-case scenario, there is no alternative but to work proactively and resolutely to enhance international diplomatic and legal instruments to prevent outer space weaponization

[1] Committee on the Peaceful Uses of Outer Space: Membership Evolution // UNOOSA, 2023.

URL: https://www.unoosa.org/oosa/en/ourwork/copuos/members/evolution.html.

[2] 2022 Annual Report of the United Nations Office for Outer Space Affairs 2022 // UNOOSA, 2023.

URL: https://www.unoosa.org/documents/pdf/annualreport/UNOOSA_Annual_Report_2022.pdf.

[3] Our Common Agenda Policy Brief 7: For All Humanity – the Future of Outer Space Governance // United Nations, May 2023. URL: https://www.unoosa.org/res/oosadoc/data/documents/2023/a77/a77crp_1add_6_0_html/our-common-agenda-policy-brief-outer-space-en.pdf.

[4] Колосов Ю.М. Предисловие к монографии / Яковенко А.В. Прогрессивное развитие международного космического права. – М.: Междунар. отношения, 1999. – С. 8.

[5] Расширенное заседание Совета Безопасности // Официальный сайт Президента России, 16 апреля 2019 г. URL: http://kremlin.ru/catalog/keywords/123/events/copy/60301.

[6] Our Common Agenda Policy Brief 7: For All Humanity – the Future of Outer Space Governance // United Nations, May 2023. URL: https://www.unoosa.org/res/oosadoc/data/documents/2023/a77/a77crp_1add_6_0_html/our-common-agenda-policy-brief-outer-space-en.pdf.

[7] Space Foundation Releases The Space Report 2022 Showing Growth of Global Space Economy // Space Foundation, July 27, 2022. URL: https://www.spacefoundation.org/2022/07/27/the-space-report-2022-q2/.

[8] Convention on Registration of Objects Launched into Outer Space / International Space Law: United Nations Instruments // UNOOSA URL: https://www.unoosa.org/res/oosadoc/data/documents/2017/stspace/stspace61rev_2_0_html/V1605998-ENGLISH.pdf.

[9] 2022 Annual Report of the United Nations Office for Outer Space Affairs 2022 // UNOOSA, 2023.

URL: https://www.unoosa.org/documents/pdf/annualreport/UNOOSA_Annual_Report_2022.pdf.

[10] Our Common Agenda Policy Brief 7: For All Humanity – the Future of Outer Space Governance // United Nations, May 2023. URL: https://www.unoosa.org/res/oosadoc/data/documents/2023/a77/a77crp_1add_6_0_html/our-common-agenda-policy-brief-outer-space-en.pdf.

[11] Ibid.

[12] Ibid.

[13] Ibid.

[14] 2022 Annual Report of the United Nations Office for Outer Space Affairs 2022 // UNOOSA, 2023.

URL: https://www.unoosa.org/documents/pdf/annualreport/UNOOSA_Annual_Report_2022.pdf.

[15] Our Common Agenda Policy Brief 7: For All Humanity – the Future of Outer Space Governance // United Nations, May 2023. URL: https://www.unoosa.org/res/oosadoc/data/documents/2023/a77/a77crp_1add_6_0_html/our-common-agenda-policy-brief-outer-space-en.pdf.

[16] The Kessler Syndrome: 10 Interesting and Disturbing Facts // Space Safety Magazine. URL: http://www.spacesafetymagazine.com/space-debris/kessler-syndrome.

[17] International Space Law: United Nations Instruments // UNOOSA, May 2017. URL: https://www.unoosa.org/res/oosadoc/data/documents/2017/stspace/stspace61rev_2_0_html/V1605998-ENGLISH.pdf.

[18] Guidelines for the Long-Term Sustainability of Outer Space Activities of the Committee on Peaceful Uses of Outer Space adopted // UNOOSA, June 22, 2019. URL: https://www.unoosa.org/oosa/en/informationfor/media/2019-unis-os-518.html.

[19] 2022 Space Doctrine Note (SDN) Operations. Doctrine for Space Operations // Headquarters. United States Space Force, January 2022. P. 15. URL: https://media.defense.gov/2022/Feb/02/2002931717/-1/-1/0/SDN%20OPERATIONS%2025%20JANUARY%202022.PDF.

[20] Ibid. P. 15-16.

[21] Our Common Agenda Policy Brief 7: For All Humanity – the Future of Outer Space Governance // United Nations, May 2023. URL: https://www.unoosa.org/res/oosadoc/data/documents/2023/a77/a77crp_1add_6_0_html/our-common-agenda-policy-brief-outer-space-en.pdf.

[22] 1963 Treaty Banning Nuclear Weapon Tests in the Atmosphere, in Outer Space and Under Water // United Nations. URL: https://treaties.un.org/doc/Publication/UNTS/Volume%20480/volume-480-I-6964-English.pdf

[23] Беркман П.А., Вылегжанин А.Н., Юзбашян М.Р., Модюи Ж. Международное космическое право: общие для России и США вызовы и перспективы // Московский журнал международного права, 2018; 106(1). С. 10. URL: https://www.mjil.ru/jour/article/view/239.

[24] Treaty on Principles Governing the Activities of States in the Exploration and Use of Outer Space, including the Moon and Other Celestial Bodies // UNOOSA. URL: https://www.unoosa.org/oosa/en/ourwork/spacelaw/treaties/introouterspacetreaty.html.

[25] Treaty on Principles Governing the Activities of States in the Exploration and Use of Outer Space, including the Moon and Other Celestial Bodies // UNOOSA. URL: https://www.unoosa.org/oosa/en/ourwork/spacelaw/treaties/introouterspacetreaty.html.

[26] Борьба за мирный космос: Правовые вопросы / Ю.М. Колосов, С.Г. Сташевский. – 2-е изд., стер. – М.: Статут, 2014. – C. 45.

[27] Resolution 34/68. Agreement Governing the Activities of States on the Moon and Other Celestial Bodies // UNOOSA. URL: https://www.unoosa.org/oosa/en/ourwork/spacelaw/treaties/moon-agreement.html.

[28] 1972 Treaty on the Limitation of Anti-Ballistic Missile Systems // United Nations.

URL: https://treaties.un.org/doc/Publication/UNTS/Volume%20944/volume-944-I-13446-English.pdf.

[29] Малов А.Ю. Предотвращение гонки вооружений в космосе. Военно-политические аспекты: монография. М : МГИМО-Университет, 2021. С. 28; Политико-правовые аспекты предотвращения милитаризации космического пространства и пути укрепления и совершенствования международно-правового режима использования космического пространства (доклад на международной космической конференции) // МИД России, 24 мая 2001 г. URL: https://www.mid.ru/ru/foreign_policy/international_safety/disarmament/1722120/.

[30] Resolutions of the 77th Session // United Nations General Assembly.

URL: https://www.un.org/en/ga/77/resolutions.shtml.

[31] Prevention of an Arms Race in Outer Space / Report of the First Committee // United Nations General Assembly, November 14, 2022. URL: https://documents-dds-ny.un.org/doc/UNDOC/GEN/N22/690/30/PDF/N2269030.pdf?OpenElement.

[32] International Cooperation in the Peaceful Uses of Outer Space / Report of the Special Political and Decolonization Committee (Fourth Committee) // United Nations General Assembly, November 01, 2022. URL: https://documents-dds-ny.un.org/doc/UNDOC/GEN/N22/666/87/PDF/N2266687.pdf?OpenElement.

[33] Ibid.

[34] Ibid.

[35] No First Placement of Weapons in Outer Space : Resolution / adopted by the General Assembly // United Nations Digital Library, 2022. URL: https://digitallibrary.un.org/record/3996913?ln=en.

[36] Предотвращение размещения оружия в космосе (ПГВК) // МИД России.

URL: https://www.mid.ru/ru/foreign_policy/vnesnepoliticeskoe-dos-e/mezdunarodnye-organizacii-i-forumy/voprosy-kontrola-nad-vooruzeniami-i-nerasprostranenia/#18.

[37] Further Practical Measures for the Prevention of an Arms Race in Outer Space : Resolution / adopted by the General Assembly // United Nations Digital Library. URL: https://digitallibrary.un.org/record/3999153?ln=en.

[38] Ibid.

[39] Letter dated 10 June 2014 from the Permanent Representative of the Russian Federation and the Permanent Representative of China to the Conference on Disarmament addressed to the Acting Secretary General of the Conference transmitting the updated Russian and Chinese texts of the draft treaty on prevention of the placement of weapons in outer space and of the threat or use of force against outer space objects (PPWT) introduced by the Russian Federation and China // Conference on Disarmament. URL: https://documents-dds-ny.un.org/doc/UNDOC/GEN/G14/050/66/PDF/G1405066.pdf?OpenElement.

[40] Draft Treaty on the Prevention of the Placement of Weapons in Outer Space, the Threat or Use of Force against Outer Space Objects // Conference on Disarmament. URL: https://cms.spacesecurityportal.org/uploads/DPROK_anglijskij_2014_e2530346b0.pdf.

[41] Ibid.

[42] Reducing Space Threats through Norms, Rules and Principles of Responsible Behaviors : Resolution / adopted by the General Assembly // United Nations Digital Library, December 30, 2021.

URL: https://digitallibrary.un.org/record/3952870.

[43] Resolution 77/41 “Destructive Direct-Ascent Anti-Satellite Missile Testing” Adopted by the General Assembly on 7 December 2022 // United Nations General Assembly. URL: documents-dds-ny.un.org/doc/UNDOC/GEN/N22/738/92/PDF/N2273892.pdf?OpenElement.

[44] Joint Statement on the Initiative on Undertaking Political Commitment not to Conduct Destructive Direct-Ascent Anti-Satellite Missile Tests // Russian Foreign Ministry, October 26, 2022.

URL: https://mid.ru/en/foreign_policy/international_safety/1835220/.

[45] Ibid.

[46] Foreign Ministry Spokeswoman Maria Zakharova’s Comment on the US Initiative in the UN General Assembly First Committee // Russian Foreign Ministry, October 25, 2022. URL: https://www.mid.ru/ru/foreign_policy/un/organs/general_assembly/1835061/?lang=en.

[47] UkraineX: How Elon Musk’s Space Satellites Changed the War on the Ground // Politico, September 6, 2022. URL: https://www.politico.com/news/2022/06/09/elon-musk-spacex-starlink-ukraine-00038039.

[48] Statement by the Head of the Russian Delegation at the First Session of the Open-ended Working Group, Established by UNGA Resolution 76/231, on the Agenda Item “General Exchange of Views” // UNOOSA. URL: https://www.unoosa.org/documents/pdf/copuos/2023/Statements/2_AM/4_Russian_Federation_2_June_AM.pdf

E16/MIN – 24/04/15