GENEVA. DECEMBER 2, 2024. PIR PRESS. On November 20, PIR Center held a seminar titled “Security Index in a New World: What Future for Arms Control?” at the UN Palais des Nations in Geneva. Organized in collaboration with the Permanent Mission of the Russian Federation to the UN Office and other international organizations in Geneva, the event marked the launch of the Security Index Yearbook.

The seminar brought together Ambassadors to the Conference on Disarmament, senior diplomats from permanent missions to international organizations in Geneva, and experts from Belarus, Brazil, Hungary, Venezuela, the United Kingdom, Egypt, Israel, India, Nicaragua, Pakistan, Kazakhstan, China, Cuba, the United States, South Africa, and other countries. Representatives from UNIDIR, the United Nations Office for Disarmament Affairs (UNODA), the United Nations Institute for Training and Research (UNITAR), the Geneva Center for Security Policy (GCSP), the Center for Humanitarian Dialogue, and the Geneva Center for Democratic Control of Armed Forces (DCAF) also attended.

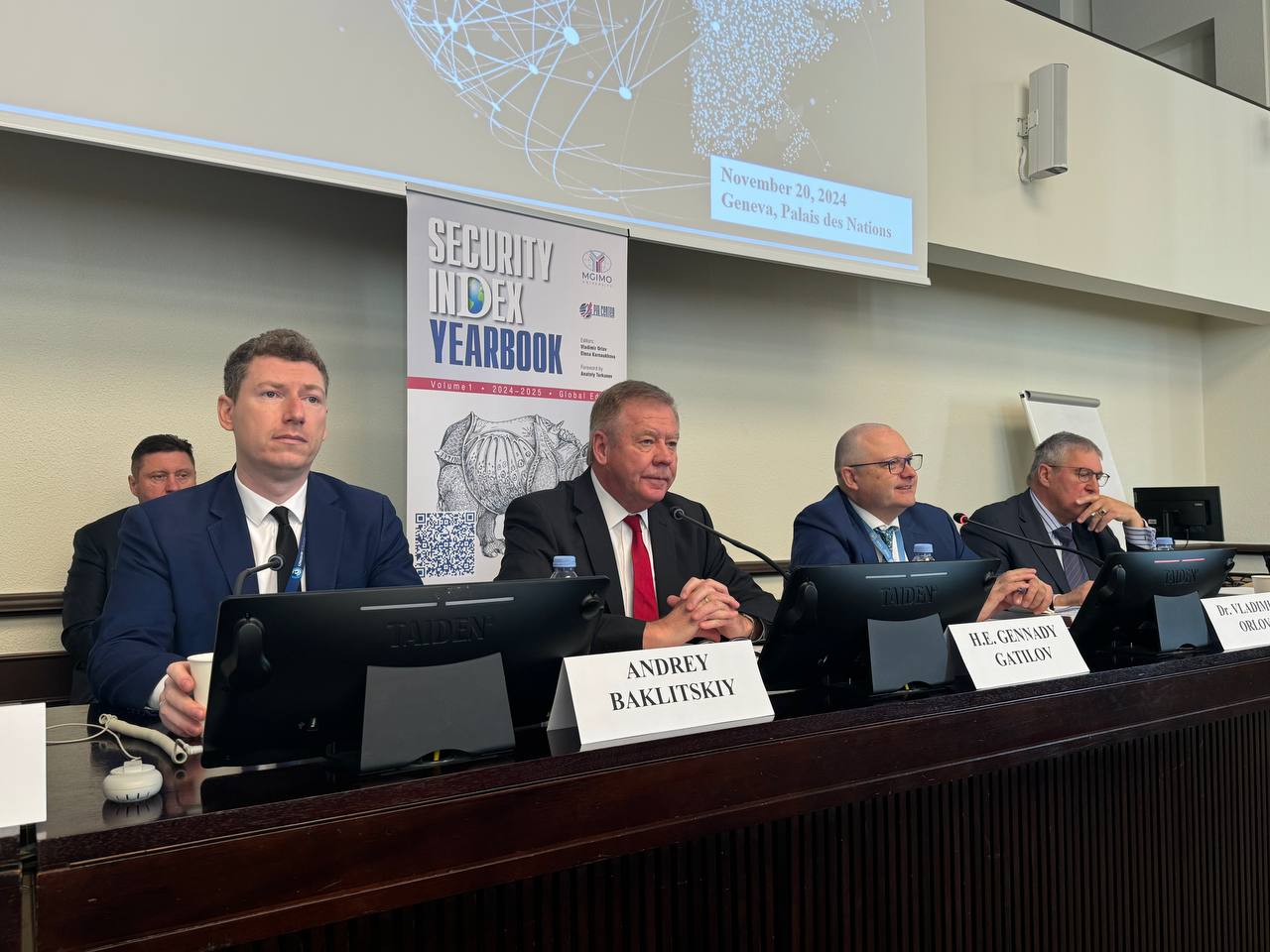

During the seminar, the Security Index Yearbook 2024-2025 was officially unveiled. The opening address was delivered by Amb. Gennady M. Gatilov, Permanent Representative of the Russian Federation to the UN Office and other international organizations in Geneva. Ambassador Gatilov emphasized the importance of highlighting Russian expert perspectives during a period of heightened international tensions: “In such circumstances, we believe that the first step in reducing the conflict potential is to search for and eliminate the root causes of fundamental contradictions. In this regard, specialized research and political science entities from various countries, such as PIR Center, can and must play an important role. Such think-tanks have the necessary potential to study the historical causes of modern conflict, they are able to provide an independent assessment of the current geopolitical realities. In addition, they have an opportunity to bring views of individual countries on the most topical issues to a wide audience when intergovernmental cooperation, through no fault of Russia, is virtually paralyzed. And by this, they can help to find compromise solutions.“

The Yearbook presentation was then delivered by Dr. Vladimir Orlov, Founding Director of PIR Center and Professor at MGIMO University. He highlighted the Yearbook’s broad coverage of international security issues and its inclusion of articles by both established experts and emerging voices in the field: “The Editorial Board of the Yearbook unites leading Russian and international experts from South Asia, the Middle East, Eurasia, and North America,” – noted Dr. Vladimir Orlov – “We have already conducted three successful presentations for a specialized international audience in Zvenigorod (Russia), Astana (Kazakhstan), and Minsk (Belarus). Today, we are in Geneva at the UN. Next stop: Abu Dhabi, for the Middle East.”

The Security Index Yearbook is the result of fruitful cooperation between PIR Center and MGIMO within the Priority 2030 Strategic Academic Leadership Program.

Dr. Vladimir Orlov followed with his opening remarks and presentation, noting that “the risk of nuclear escalation, event of a nuclear war, is today higher than in recent decades. Needless to say, in today’s reality, escalation involving non-nuclear components, including medium range missile systems, is going on, and we all are witnesses to it. We have a war in Europe – a hybrid war between NATO states and Russia, in which interconnection between ‘nuclear’ and ‘non-nuclear’ has become a sensitive factor of growing importance.”

“Some suggest ‘compartmentalization’ as a solution,” – he continued. “However, this approach is misleading and unfeasible. What is needed is a holistic approach to strategic stability, including a comprehensive reconstruction of European security architecture in the context of Eurasian security. This would provide a foundation for future negotiations when conditions permit.”

“Don’t take my opening remarks as gloomy ones, however,” – stressed Dr. Vladimir Orlov. “What we are witnessing now is a dramatic, impressive, and very dynamic change in the whole international security landscape. And it is not a bad thing at all! The recent BRICS Summit in Kazan demonstrated that positive security approaches are not only possible – they are in high demand by the Global Majority of nations, some of whom are outspoken and others silent and in observing mode so far. Eurasian security construction planning is on the rise.”

“What does it all mean for today’s roundtable’s primary topic – arms control?” – Dr. Vladimir Orlov addressed the panel – “Is arms control dead? Not at all. May I suggest that arms control goes in cycles? Now, one should be prepared – and patient – for a long, long cycle when it is put on hold. One should use this pause for at least two exercises: first, to keep the institutional memory of past negotiations, preparing the younger generation of arms control experts for their future mission. Secondly, to use platforms like today’s roundtable to think creatively about how new arms control should look.”

Dr. Vladimir Orlov’s presentation is available at the link.

The digital version of the Security Index Yearbook is available at the link. Also, a photo gallery of the event has been published on the PIR Center website.

The seminar featured a panel discussion that delved into the perspectives of the Yearbook’s contributors and analyzed contemporary challenges in international security. Speakers included UNIDIR expert and member of the PIR Center Advisory Board Andrey Baklitskiy; PIR Center Consultant and Yearbook’s contributor Alexandra Zubenko; and Col. (Retd.) Bruno Russi, former Swiss military attaché in Moscow, member of the PIR Center Advisory Board.

Summaries of Speakers’ Presentations:

Andrey Baklitskiy, Future for Arms Control in Europe:

- The future of arms control in Europe cannot be seriously discussed without considering broader global changes. Current uncertainties, including the prospects for foreign policy under the new US administration, underscore the need to create comprehensive approaches to solving security challenges that consider the interrelationships between global and regional dynamics.

- Arms control remains an essential foreign policy tool historically used by strong leaders to enhance international security and reduce defense spending. Its relevance extends beyond Russian-American relations; for example, the Agreement on the Mutual Reduction of Armed Forces in Border Areas among Russia, Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, Tajikistan, and China demonstrates its utility. Presenting arms control as a sign of weakness overlooks its historical role in fostering stability and trust.

- While nuclear disarmament remains the ultimate goal, immediate actions such as maintaining a moratorium on nuclear testing and freezing the arms race are critical interim steps to prevent further degradation of strategic stability.

- Future arms control agreements should adopt a holistic approach to the “strategic equation,” addressing nuclear and non-nuclear factors, offensive and defensive capabilities, and emerging areas like the prospect of an arms race in outer space.

- Europe must be integrated into broader arms control efforts that tackle specific issues, such as intermediate-range missiles and the confrontation between Russia and NATO.

Col. (Retd.) Bruno Russi, The Role of Diplomacy in Arms Control:

- In recent years, we have witnessed the erosion or collapse of many critical elements of the security architecture that was established even during the tensest times of the Cold War. At the same time, many diplomatic doors are being closed, and vital international institutions like the UN Security Council and the OSCE are being weakened. What are the consequences for arms control?

- Diplomacy remains a crucial element of arms control and disarmament – essential if the world wishes to avoid facing more dangerous alternatives. Diplomacy takes many forms, including multilateral diplomacy, bilateral diplomacy, and more informal formats such as “Track 1.5” and “Track 2” diplomacy.

- An important yet often overlooked aspect of arms control diplomacy is the expert advice provided in the background. The increasing complexity of weapons systems and delivery vehicles, as well as the risk of proliferation to transnational criminal groups, demands in-depth knowledge of the strategic, operational, and tactical aspects of these systems. Additionally, expertise is required to address the potential for illegal production or acquisition of sensitive materials.

- In addition to multilateral diplomacy, bilateral diplomacy plays a significant role in arms control and disarmament, particularly between nuclear powers. Bilateral diplomacy often begins with exploratory discussions and extends to supporting existing arms control venues, discovering new ones, assessing structures, positions, and options, analysing interests, and advising and supporting delegations.

- Smaller states can also make a difference. For instance, Switzerland developed its own Arms Control and Disarmament Strategy for 2022–2025. Key elements of this strategy include eliminating weapons of mass destruction and reducing the impact of armed violence. However, the strategy goes further, addressing new domains such as cyberspace and outer space and developing norms to govern the use of emerging technologies in conflict, such as autonomous weapons systems.

- “Track 1.5” and “Track 2” diplomacy offer significant advantages for arms control and disarmament, as demonstrated by initiatives like PIR Center’s efforts. “Track 2” diplomacy, originally defined as unofficial and non-structured interaction, is characterized by open-mindedness, altruism, and strategic optimism. It leverages human goodwill and reason to bring experts from various fields together, fostering the generation of new ideas and enabling informal yet substantive discussions. This format is based on expertise and mutual respect, where consensus is not a requirement, making it a valuable tool for advancing complex issues.

Alexandra Zubenko, Russia’s Proliferation Threat Landscape: Strategies for Effective Communication and Countering:

- Threat 1: Vertical proliferation/build-up of the U.S. nuclear arsenal. The Republican Party is known for adopting more hawkish policies, particularly in nuclear matters. In recent years, there has been significant debate in Congress about whether the U.S. should expand its nuclear arsenal. In 2023, a U.S. Congressional Commission on Nuclear Posture, where Republicans were well represented, concluded that America should be prepared to address the dual nuclear threats posed by Russia and China and deploy more warheads than those currently allowed under New START. Figures like former Trump Security Advisor Robert O’Brien have stated that the U.S. must maintain numerical and technical superiority over both adversaries. Additionally, newly appointed National Security Advisor Mike Waltz has emphasized the need to deter China militarily.

- Despite these calls for a build-up, the U.S. faces budgetary constraints that limit large-scale expansion. For instance, deploying additional warheads using existing delivery systems would cost around $100 million – a relatively modest investment. However, effectively countering both Russia and China would require developing new delivery platforms, a far more expensive undertaking, estimated at $172 billion, with $8 billion in annual maintenance. This would elevate the existing cost by around a third, posing a significant constraint for any administration over the next 15 years. Modernization expenses have already surged by nearly 20% in two years, totaling $756 billion.

- Threat 2: Heightened proliferation risks in the Asia-Pacific region. In the past three years, interest in acquiring nuclear weapons has resurged in the Asia-Pacific. A 2024 study by the Center for Strategic and International Studies (CSIS) found that 76% of South Koreans now support nuclearization, with half favoring an independent deterrent. In response, the U.S. has sought to reassure South Korea by enhancing security commitments, such as establishing a Nuclear Consultative Group and deploying nuclear-armed assets – unprecedented measures compared to the last 40 years. Yet, despite these efforts, the South Korean Ambassador recently mentioned that his government intends to discuss nuclear reprocessing technology with the U.S., which poses a significant proliferation risk. While the U.S. is unlikely to entertain this suggestion, it reflects a persistent interest in independent nuclear capabilities despite U.S. security assurances. Furthermore, the Asia-Pacific region faces the growing challenge of dual-use technologies. Earlier this year, Japan made a deal to acquire 400 Tomahawk cruise missiles, which have dual-use potential. Additionally, the U.S. deployed advanced systems to the Philippines, with unconfirmed allegations suggesting these assets may remain permanently.

- Threat 3: Proliferation challenges in the Middle East. The ongoing conflict in Gaza has derailed significant diplomatic progress, including negotiations over the Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action (JCPoA) with Iran. Unofficial U.S.-Iranian discussions have stalled since October 2023. This situation is compounded by America’s unwavering military support for Israel and the lack of any viable diplomatic initiative in the Middle East, exacerbating nonproliferation risks in the region. However, there are ongoing nonproliferation discussions outside the Middle East, such as the Conference on Establishing a Middle East Nuclear-Weapon-Free Zone currently happening in New York. These discussions have achieved some successes over the last five years, despite Israel’s absence. There are also promising developments, such as the engagement of Middle Eastern nations with BRICS. In recent years, countries like Egypt, Saudi Arabia, the UAE, and potentially Turkey have sought closer ties with BRICS, where nonproliferation has featured prominently.

- Additionally, there is growing momentum for nuclear energy cooperation through initiatives like the Nuclear Energy Platform, which offers secure, no-proliferative energy solutions. This demonstrates that in times of crisis, forums like BRICS – offering more flexible and non-ideological platforms for dialogue – can provide opportunities for finding common ground in some areas of concern.

Key words: Global Security; Security Index Yearbook; United Nations

RUF, SIY

F4/SOR – 24/12/02