Exclusive Interview

PIR Center interviewed Dr. Dmitry Polikanov, Deputy Head of Rossotrudnichestvo. During the conversation, we discussed the concept of Russian soft power, whether it is an effective instrument in international relations or merely an illusion, various aspects of the definition of soft power, Russia’s strategies and objectives, and the effectiveness of these strategies in the global arena.

The interview was conducted by Ksenia Mineeva, former PIR Center Information & Publications Program Coordinator.

Ksenia Mineeva: What impact has the Special Military Operation in Ukraine and the escalation of international tensions had on Russia’s positioning in the global arena?

Dmitry Polikanov: The start of the Special Military Operation in February 2022 seriously corrected Russia’s image abroad. One may say that there is nothing new about it – intoxication[1] began long ago, already in 2014 with the accession of Crimea or the conflicting view over the Malaysian Boeing case, let alone Novichok allegations and the social media hype over the opposition-minded Alexey Navalny who was clearly defined as a foreign agent. However, drastic changes that resulted from Russia’s new assertiveness and the use of force to defend the population in the South-East of Ukraine overturned the Grand Chessboard[2] and added turmoil to the global economy and politics.

As a result, this created a significant demand for new approaches towards positioning the country in the international arena as well as more coordinated and proactive efforts to convey to the world the key provisions of the Russian foreign policy and the fundamental values underpinning them. After all, Moscow pretends to be one of the poles in the international order and should be able to explain to other actors its national interests and the attitude towards the existing institutions.

For a long time, the Russian Federation had been regarded as a status quo power trying to preserve its weakening privileges in global affairs by conserving the Yalta-Potsdam system of international relations. Many would call Moscow enfant terrible[3] of the 21st century with its Andrey Gromyko’s Mister No style and inability to formulate the positive agenda for the future – be it the reform of the United Nations, the climate change, or a new architecture of regional security in some sensitive areas of the world. It can also be remembered how humiliating was for Russia its comparison with Upper Volta with rockets[4]pointing at Russia’s lame economic potential inconsistent with its global ambitions.

Nowadays the situation is different. Difficult times and the revival of the ideological resentment in a rapidly changing, unpredictable and generally inapprehensible world require a clear set of values and national objectives. In the last two years Moscow has managed to formulate them anew in the strategic documents – from the National Security Strategy to the updated Foreign Policy Concept and the Humanitarian Policy Concept of the Russian Federation.

Ksenia Mineeva: How does Russia define its values and national interests today?

Dmitry Polikanov: The National Security Strategy formulated 17 traditional values for the Russian multiethnic nation, which are normally reduced to three major guidelines – family, history, patriotism[5]. That means traditional family formed by a man and a woman[6], resistance to the falsification of historical truth and the devotion to serving your country. However, they are much broader and contain among others the rights and freedoms of citizens for life and dignity, constructive labor, priority of spiritual over material, collectivism, charity, mutual assistance, and mutual respect.

These values lay the foundation for further actions of the state on the global arena. They demonstrate Russia’s commitment to conservatism in close connection with progress. Methodologically they are opposed to neoliberal values with their absolutization of freedom and excessive concern about various minorities, the protection of whom becomes more important than the sentiments of the majority. Partly this indicates Russia’s response to the future world with its antihuman approaches – since people are less needed for the production of goods and create extreme burden for the environment, they can be replaced with artificial intelligence and robots which results in the promotion of child-free policies, multiple genders and LGBT agenda[7].

Besides, the Humanitarian Policy Concept emphasizes that Russia is committed to the principles of equality, justice, and non-interference in internal affairs of other states. The country is ready for mutually beneficial cooperation without preconditions and recognizes national and cultural identity and traditional spiritual values as the greatest achievements of the mankind and sees them as a basis for the successful progress of human civilization[8].

The 2023 Russia’s Foreign Policy Concept for the first time articulates clearly that the country is a civilization by nature, with a complex mix of its European and Asian roots. Moreover, Russia great claims itself as a great power in the Eurasian and Euro-Pacific region with its own world vision. The mission of the nation is to promote a fair and multipolar international order based on law (and not simply rules), to struggle against hegemonies (e.g., the collective West) and in favor of preserving the concept of sovereignty (which has eroded in the recent decades). The key foreign policy objectives serve to ensure Russia’s security and favorable external conditions for development[9].

Ksenia Mineeva: How have Russia’s geographical priorities been transformed?

Dmitry Polikanov: Under these circumstances, they are also clear. The key area for potential cooperation is the so-called Near Abroad, i.e., Russia’s neighbors which are organized into regional coalitions – from the Eurasian Economic Union (EAEU) to the Organization of the Collective Security Treaty (CSTO) and the Commonwealth of Independent States (CIS), which is sometimes called as the relic of the civilized divorce of the Soviet Union republics[10]). They are followed by the Arctic region with its immense and unexploited resources as well promising transportation routes. Then comes big Eurasia including China, India, the Asia-Pacific region, and the Islamic world – Russia’s pivot to the east proclaimed many years ago is finally reflected in the official documents. The next step is Africa – the continent of the 21st century which, like in the 19th century, becomes again the arena of global confrontation between some neocolonial powers. And last but not the least is Latin America and the Caribbean which are far away from Russia but demonstrate significant interest in maintaining ties with our country, including political cooperation[11].

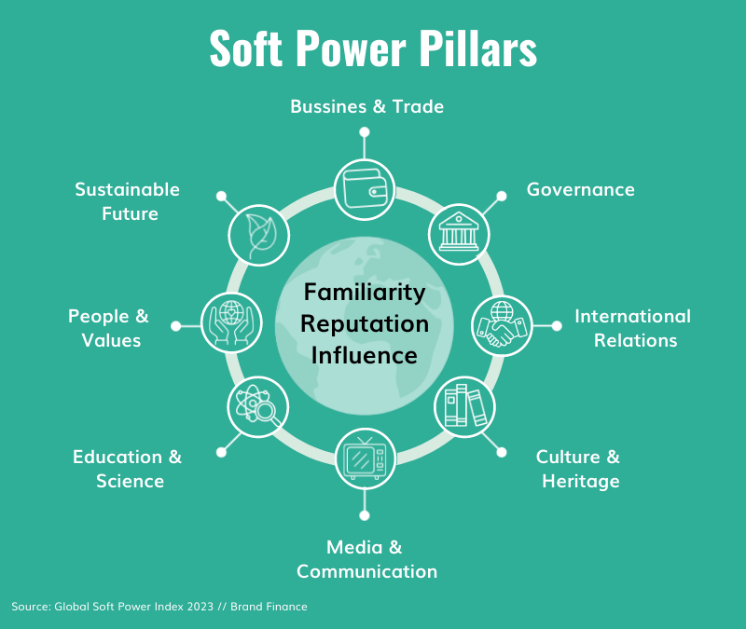

Ksenia Mineeva: How do the above-mentioned values and priorities influence the formation of Russian soft power? What are its mechanisms aimed at?

Dmitry Polikanov: For sure, all this provides the setting for the Russian soft power positioning. Our main efforts are focused on demonstrating that Russia is not isolated in this world despite the sanctions, and that its policy reflects the aspirations of Global Majority. As Vladimir Putin put it in his remarks at the Valdai Discussion Club Forum in 2023, the future world order should be based on six major pillars: the elimination of barriers for prosperity and self-fulfillment, preserving diversity, collective approach towards decision-making by the responsible parties concerned, respect to the interests of all states, universal justice and equitable access to the benefits of the progress, as well as equal rights[12].

This vision of the future and Russia’s global ambitions find their proof through various mechanisms. The most traditional ones are the permanent seat in the UN Security Council and constant reminders of the rapid upgrade of the Russian nuclear arsenal, with its superweapons capable of overwhelming all modern systems of defense[13].

However, peaceful agenda also makes its contribution. Moscow expands its official development assistance and tries to make it more visible. This requires the shift from traditional UN aid supply chains to bilateral cooperation – be it vaccines, grain, fertilizers, or the construction of Russian schools abroad. Such an approach helps to minimize administrative and traditional UN overhead costs (as well as some inevitable abuses in distribution) and makes Russia’s aid visible, especially if it is accompanied by an appropriate information support. The government points out that such assistance has no political bias, does not demand reciprocal steps from the recipients, does not lead to the outflow of resources from them and has purely humanitarian nature[14]. All this distinguishes it from the neocolonial aid mechanisms which only strengthen the dependence of the so-called third world countries on the golden billion.

Russia tries to contribute to the environmental agenda including climate change and global green energy transfer. The country does not neglect the UN Sustainable Development Goals (SDG) and elaborates its own ESG-standards for their further proliferation across the globe[15]. Moscow has several times attempted to promote the regulation of artificial intelligence (AI), as well the codification of the information security norms to meet the challenges of the upcoming decades[16].

Another focus of the Russian efforts is resistance to Russophobia – the rise of anti-Russian sentiments, especially after February 2022. In spring 2022, it became extremely dangerous for people to refer to their Russian roots – be it an organization of cultural events or making mortgage payments. Russian compatriots in Europe, Canada and the United States faced discrimination and humiliation, direct attacks and bullying in social media. Many cultural events were cancelled and even the names of the world art masterpieces were revised, as is the case for the Metropolitan Museum in New York[17]. Quick response including legal action helped to abate this negative wave, and common sense has prevailed in the end. Nonetheless, Russophobia has turned out to be such an attractive concept for the politicians on both sides that they fell into the classical trap of human mind – self-fulfilling prophecy, an ability of human brain to deliberately select facts to prove its case.

As a result, Russophobia comfortably explains the need for mental warfare. It is another fashionable notion in the arsenal of Russian philosophers, military experts, and political strategists. They accuse the West of trying to win the minds of the colonies’ populations as it becomes more profitable than the occupation of territories[18]. In the West they have their own cliché of that kind – Russian propaganda and Ruscism[19], which help to forget about freedom of speech, violate the rights and use their countries’ budgets for counterpropaganda.

Ksenia Mineeva: What role does the concept of Russia as a country of opportunities (RCO) play in its positioning in the world arena? How is the RCO concept implemented?

Dmitry Polikanov: The country has developed the concept of Russia as a country of opportunities (RCO) for internal use. It has already managed to change the attitude of the Russian youth towards patriotism and the future of the nation through various projects aimed at self-fulfillment and social elevation mechanisms. Nowadays, 76 percent of the Russian young people believe that they can realize their dreams in Russia[20]. This idea turns out to be advantageous also for international positioning. This explains Russia’s endeavors to hold the World Youth Festival on the Sirius Federal Territory in March 2024, to establish a new annual Russia-Islamic World, the KazanForum, to host various remaining international sports competitions from which Russian athletes are not banned for doping, etc.

One of the key elements of the RCO concept is Russia’s system of education, which is competitive and attractive at both secondary and higher levels. The Russian government has raised the annual quota for free university education up to 30.000 students. Despite the sanctions, logistical difficulties, and some problems with payment systems in 2022, there are about 300.000 foreign students getting education in Russia[21], nearly 90 percent of whom take commercial courses and pay tuition fees as well as all other expenses for their stay in the country.

Education means language and the state is very much concerned about the promotion of the Russian language abroad. It is evident that number of Russian-speaking people is declining due to demographic problems inside the country, harsh attitude of the Ukrainian authorities to the Russian language and the efforts to eliminate any signs of Russian imperialism[22], fierce promotion of national languages in the former Soviet Union (from Latvia to Kyrgyzstan) and generational change. The last Soviet generation who studied proper Russian at school reaches its fifties, while young people prefer local languages or English, Turkish and Chinese[23]. The annual Russian Language Index published by the Puskin Institute ranks Russian as the 5th most used in the world, but this results from the large number of Russian-language websites, the official use of Russian in many international organizations and numerous academic publications[24]. Frankly speaking, without it Russian would be somewhere on the seventh-eighth place. Since the language continues to be one of the major criteria to identify the affiliation with the Russian World, the situation causes grave concerns.

To overcome this problem, in 2021 Russia adopted a special complex national program Support and promotion of the Russian language abroad which aims at coordinating the efforts of various actors in this field and provides for a fair distribution of financial resources. The plan implies different activities from language courses, festivals, advanced training of teachers to the establishment of the resource centers giving additional training in some subjects in Russian.

Ksenia Mineeva: How favorable are these settings for the Russian positioning in the global arena?

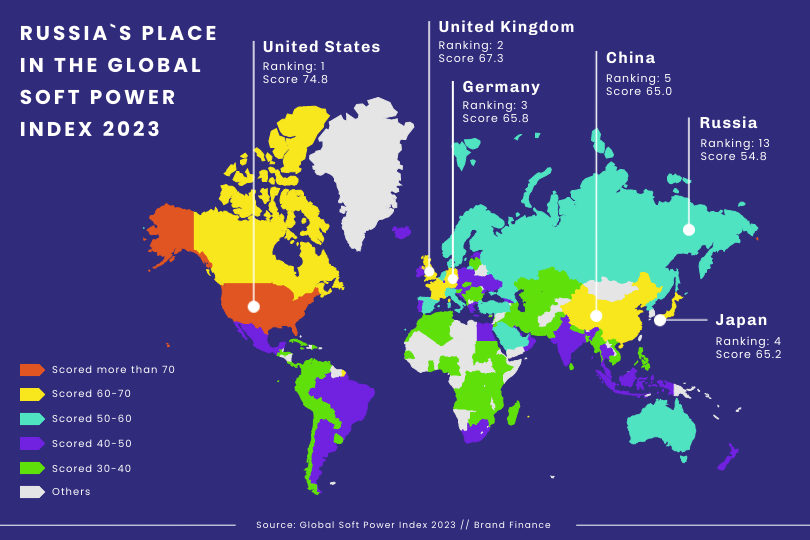

Dmitry Polikanov: It is important to look at the sociological data to understand how Russians perceive themselves and how they are viewed in other countries.

Public opinion polls indicate that Russia is a peaceful country promoting such values as kindness, mutual assistance, fairness and commitment to conscience and spirituality. At the same time, it is doomed to be a great power, or otherwise it will be a tasty morsel for other international actors due to its enormous territory and immense resources. The Russian bear is believed to be quite lonely in the eyes of the population[25] – it lacks true allies but does not stop its movement towards a new multipolar world based on equality and mutual respect. It can indulge in saber rattling but prefers to be attractive to others especially socially and economically[26].

The world perception of Russia is different. In 2022, Russia moved down in the Global Peace Index to join the group of most troubled countries including Syria, Yemen, and Afghanistan, as it was in the previous years[27]. According to the Pew Research, the majority of respondents in nearly 40 countries consider Russia to be a threat to the security of their nations (and even in 2017 this figure was not much better)[28]. The participants of the US News and World Report survey in 36 countries call Russia a global threat (72 percent) that exceeds China (66 percent) and the United States (50 percent)[29]. The results are even worse in the neighboring countries, such as Finland, Poland, or Japan. Russia also backslid on the list of the best countries in the same survey.

All this discrepancy in the image perception may be explained by the bias against and the demonization of Russia in the last years. Nonetheless, it also reflects the weakness of its efforts to improve its influence on the minds of people in various countries, i.e. the limits of Russia’s soft power mechanisms.

Ksenia Mineeva: What are the major impediments for the Russian soft power advancement?

Dmitry Polikanov: Simply put, the main obstacles for the expansion of Russia’s humanitarian influence can be divided into external and internal.

External constraints relate to various sanctions introduced against Russian authorities and institutions. Different packages of restrictions led to the fact that in the Western world the activities of Rossotrudnichestvo (the Federal Agency for International Humanitarian Cooperation), major funds (such as Russkiy Mir Foundation, or the Fund for Legal Aid and Support to the Compatriots Living Abroad), Russian media outlets (such as RT and key Russian TV channels) and think tanks (e.g. the Russian International Affairs Council, RIAC) were blocked. Financial transactions are limited except household payments (such as housing and utilities). Some countries practice mass expulsion of Russian diplomats, some of whom have also been involved in the implementation of humanitarian projects. Much depends on the position of individual countries within the EU After all there are always different ways to circumvent the sanctions and to maintain at least cultural diplomacy. However, the comeback to the normal functioning the way it was before February 2022 is unattainable. The media can try to reach their audience via the Internet and social networks, think tanks can continue to organize online events with the participation of foreign experts but generally speaking, the possibilities for maintaining the dialogue have been significantly reduced.

Another problem is censorship in social media, which today present the most popular source of information for people across the globe. Many networks (as they belong to large corporations) started to block pro-Russian content and impede the work of Russian official websites what makes them no longer accessible from abroad. Renewed actions of troll factories led to the disinformation overflow about Russia including mass production of fake news[30]. The promotion of content is also constrained for the duality of reasons – partly, due to the SWIFT cut-off and restrained availability of services for the users with Russian IPs, partly because Facebook, Instagram, Twitter or Tik-Tok are declared as extremist organizations in Russia and, hence, funding them is strictly prohibited and severely punished[31].

One can add to this some sort of self-censorship on maintaining business contacts with Russians in many countries – people unofficially declare the need for continuation of business as usual but in fact refer to political climate and try to avoid reputational risks, persecution by Ukrainian activists, and so on. The same relates to the work of international institutions – in many cases, it becomes difficult for Moscow to ensure the voting in favor of its resolutions at the United Nations, or to support the appropriate candidates for top offices in various multinational structures. Even key partners of the Russian Federation prefer to adhere to neutrality, be it the former Soviet republics or African states[32]. Their governments do their best to balance between the Western policies and the desire not to spoil relations with Russia, while pursuing their own national interests. Some are quite successful in getting concessions on both sides and in promoting domestic nation-building at the expense of conflicting giants.

Ksenia Mineeva: What are the internal obstacles to the promotion of Russian soft power?

Dmitry Polikanov: Internal barriers are also excessive. Some of them are related to the administration and coordination of the soft power promotion in Russia. It is still at the periphery of the attention of political authorities and there is no single leader who would lobby it within the elite and provide for adequate funding of the activities in this area. Unlike youth policy or integration of the new regions, soft power is not on the list of priorities. Hence, the budget of Rossotrudnichestvo, for instance, has not changed much in the recent years and amounts to about 4 billion rubles[33]. This makes only 40 million dollars for the work in the entire world at the current exchange rate as of October 2023, much of which goes to the salaries of employees and maintenance of buildings. This is not sufficient at all with the current air ticket prices, complicated logistics (after the closure of the European air space) and general inflation which affects the global economy. Unlike the Soviet Union which could afford to subsidize its influence, Russia’s financial assets are much more modest and are no longer comparable even to Sweden (which spends 2 billion euros on the Swedish International Development Agency[34]).

Another issue is the diversity of efforts and actors in humanitarian action. There is a dozen of ministries that are involved in the process through different projects and practice the silo approach, despite the supreme role of the Russian Foreign Ministry as it is enshrined in the legal acts. Numerous guidelines are issued – they are overlapping or sometimes even contradict each other. One should also bear in mind direct orders given by President Putin and the government ad hoc instructions after official visits – they aggravate the bureaucratic turmoil. Let alone the activities of business (within the framework of the corporate social responsibility policies), Russian regions (that have their own plans for international cooperation, which are not standardized), as well as nongovernmental organizations (NGOs) whose major objective is to obtain the grant and execute it in accordance with their vision of public diplomacy that often does not go beyond the hobbies of organization’s leaders. All these leads to the dispersion of scarce resources and permanent duplication of soft power endeavors.

Ksenia Mineeva: What steps are being taken by the Russian government to address these problems? How effective are the measures taken?

Dmitry Polikanov: There are some efforts to bring them under a single umbrella. A few complex state programs like the one on the Russian language and the other on the international development assistance were set up to monitor at least the key measures[35]. New department was established within the Russian Foreign Ministry to create and maintain the dashboard for humanitarian action[36]. Rossotrudnichestvo prepared methodological guidelines for the regions and municipalities concerning international cooperation – they are aimed at introducing some standards in the management system (unified structure) as well as planning. However, this work is yet at the initial stage.

Basic principles of the system imply that it is focused on reporting and keeping formalities rather than formulating clear key performance indicators (KPIs) that would focus on the output not on the process. Organic bureaucratic culture stands for the medical principle of inflicting no harm – it prefers stability and, in exceptional cases, some passive reaction rather than proactive approach. The staff overseas concentrates on classical diplomatic duties, i.e., collection, primary analysis, and transfer of information (frequently required for the complacency of their superiors[37]), rather on political technologies to attract, involve and mobilize various audiences through decent work with the leaders and opinion-makers. Most of the media activities are based on the resources of the international bureaus of the Russian, not foreign media – they mainly make up the pool of journalists for embassies. Thus, the information is closed within the quasi-international circuit but is actually designated for internal use in Russia mostly, since TASS or Sputnik news agencies are not extremely popular among the locals (with exceptions of some countries, of course[38]). No wonder that Russia loses media warfare[39] – the channels for spreading an objective and unbiased information about the country are extremely limited.

One can add to this the internal contradictory signals. For instance, on the one hand, Russia is interested in developing international cooperation – be it sister cities, or compatriots abroad, or NGOs, or scientific diplomacy and student exchange. On the other hand, the country adopts a legislation that tightens control over contacts with the foreign actors and kicks off paranoia about foreign funding (including money coming from the ally countries, such as EAEU members)[40]. The media climate and the statements of some politicians promote total spy-hunting and intimidate the newly relocated Russian diaspora abroad[41].

The discrepancy between the statements and reality becomes evident from time to time. For instance, according to the conceptual documents Russian foreign policy is supposed to provide favorable environment for the internal development. Meanwhile, in reality (even without considering the issue of sanctions) there is no even formal connection in the documents with the national development goals and national priority projects that are implemented by our government. Or it is quite difficult to promote traditional family values when official statistics indicates that the number of divorces in Russia nearly equals the number of marriages in the first semester of 2023[42], and a lot of children are born out of wedlock.

Ksenia Mineeva: Could you expand on major tools available for the promotion of Russia’s humanitarian influence abroad?

Dmitry Polikanov: They are petty numerous but overlapping, what makes them less efficient. Many activities are concentrated on the expansion of the usage of Russian language abroad. They include different academic competitions (contests for the knowledge of the Russian language, for example) at international and national levels – the winners get extra points to enter Russian universities. Quite often when it comes to national level some governments take advantage of these contests to push through their own agendas – a bright example is Azerbaijan, where pupils of the Russian-language high schools in the last two years have to compete in the knowledge of Azerbaijani history and literature[43].

Another tool is the development of infrastructure – support to the Russian-language departments at universities and opening of the Russian corners. This has been done for many years by Russkiy Mir Foundation in libraries and universities, but their function is mostly confined to the collection of books and organization of the modest range of events (due to the problems with further maintenance and the lack of market-based wages for the staff). A new concept of the Ministry of Education implies the creation of resource centers of extra-curriculum education which are primarily established at private educational institutions – Russian-language or bilingual schools, cultural facilities or universities, etc[44]. The ministry provides the equipment (in most cases without the IT-component) and methodological support.

Besides, Russia has recently started the process of constructing secondary schools (in accordance with Russian educational standards) in the countries of the former Soviet Union – five of them were opened in Tajikistan in 2022[45] and proved successful despite their expensiveness (especially compared to the construction costs in Russia). Such facilities become the point of attraction for the local elites and function as resource centers for other Russian-language schools in the region. New projects imply the construction of five schools of the same design in Kyrgyzstan[46], and more countries are in the process of negotiations.

Several agencies have their own programs to supply textbooks and literature in Russian to schools, libraries, and universities. Not to mention that Russian regional governors and federal officials have acquired a good habit of bringing with them boxes of books during their visits abroad particularly to the CIS countries. Despite all these endeavors (several hundred thousand copies) and regardless of the abuses (when freely supplied books are then sold at the market by locals), the volume of supplies is miserable compared to the actual demand (if the goal is to provide help to millions of pupils, students, and teachers).

People make difference in the modern world. In many cases teachers of the Russian language belong to the older generation and their skills were formed in accordance with the Soviet teaching methods; they are not susceptible to innovations in language training. There are no stimulating payments for teaching Russian or in Russian and there is an increasing shortage of Russian-speaking teachers of other subjects, such as mathematics, history, or geography. To improve the situation, there have been set up various annual courses within diverse formats including summer schools, conferences, Russian-language weeks, contests, etc. organized by different actors – from the Ministry of Education and Rossotrudnichestvo to regional universities and the Pushkin Institute. Besides, Russian teachers are seconded by the Ministry to work abroad or are sent there as volunteers, e.g., via such programs as the Ambassadors of the Russian language (283 participants since 2015)[47] and Masters of the Russian language (90 people in 3 years). In some cases, all these low-scale activities overlap or do not take into account the level of skills of local teachers, and this decreases their effectiveness and does not help in solving the real problems of motivation.

The root cause here is the inappropriate interest of national governments towards promoting Russian, as their focus is on identity-building and the promotion of their own languages. Russian loses its positions as the second official language, turns into a working language and a tool for migrants striving to get to the labor market of the Russian Federation. Hence, young teachers in these countries do not see any career possibilities or monetary benefits in choosing Russian as their future profession. A way out could be the engagement of the International Organization on the Russian Language established under the Kazakhstan initiative in 2023 within the CIS. However, its mandate duplicates the powers and functions of the abovementioned actors, therefore its success depends on the ability to streamline them all, which will most probably be not the case.

Ksenia Mineeva: But what about the sphere of education?

Dmitry Polikanov: In the sphere of education, the Russian government provides 30.000 scholars and fellowships for potential university students and post-graduates. The number has increased threefold since 2013[48] but is applied only to about 10 percent of the foreign students, studying in Russia. Besides, they do not cover travel and some other essential costs – together with fears about safety in the current geopolitical situation which hampers the inflow of students.

Nonetheless, Russian universities continue to be an attractive goal for many people in CIS, India, Vietnam, or Africa, especially when it comes to training in medicine, agriculture, or engineering. Every year they hold educational exhibitions and fairs together with Rossotrudnichestvo, as well as employ other marketing tools to increase the outreach – from public lectures to opening pre-university courses in other countries, as well as benefiting from the alumni associations.

The major drawback of the system is its non-holistic approach. A potential student gets into the hands of different ministries and agencies on his way to a university and within the university, and this is not always well coordinated, or not coordinated at all. Afterwards he or she does not get any assistance in getting employment or career growth. This makes it a challenging soft power tool, even though many alumni manage to get top positions in business and in government of their countries, especially in Africa.

Ksenia Mineeva: In your personal life you are actively taking part in theatrical performances and pay much attention to traditional arts in general. How can you assess different cultural products of this kind as a tool for the promotion of Russian soft power abroad?

Dmitry Polikanov: In terms of promoting Russian cultural product, the major focus is on traditional art – folk or classical music and dance, as well as exhibitions of different kind. The Ministry of Culture conducts Days of Russia and Russian Seasons several times a year with the tours of symphonic orchestras and ballets. In 2023, it also launched a comprehensive program to support neglected Russian drama theaters abroad[49]. Those of them who follow the traditions of the Russian theater school and stage the performances in Russian are renovated, get new sound and light equipment and new opportunities for cooperation and joint activities with the best drama theaters in Russia. A number of special festivals for them is organized in Saint Petersburg and other regions as well. All this may help to resolve the similar problem as with pedagogical community – the ageing generation of actors, directors, and management in the Russian drama theaters in other countries.

Russian movies can also be a very promising soft power tool. Unlike many countries, Russia has a well-developed cinema sector and can produce export-oriented contents (as well as to help other nations with their film production). The major difficulties here are the specific stories (which are not always understandable to the foreign audience, as they are based on national realities, involve actors and music that are known mainly in Russia) and the copyright problems. Russian movie companies’ concerns about possible leaks makes it quite difficult to hold non-commercial movie shows or to supply foreign TV-channels with free Russian content. Besides, most of the embassies and cultural centers abroad do not possess special DCP-equipment to show movies, while leasing a movie-theatre can be quite expensive.

Roskino (a special GO-NGO established by the Ministry of Culture) with its limited budget conducts Russian movie festivals and Days of Russian Cinema abroad, as well as invest in the promotion of the movies at different online platforms (together with Rossotrudnichestvo). Nonetheless, these are non-regular one-time events held mostly on the promising commercial markets and available to a narrow circle op people such as movie professionals, Russian and friendly countries’ diplomats, and Russian compatriots abroad rather than to general public.

Ksenia Mineeva: What initiatives is Russia implementing with regard to youth policy and civil society development?

Dmitry Polikanov: Russia’s activities in this area have a good but underestimated potential. In the recent years, the country has managed to launch a large number of different youth projects that enhance teenagers’ and students’ self-fulfillment opportunities. Some of them are united under the RCO brand, others set up various organizations be it Tavrida Academy for Creative Industries or renovated children camps on the Black Sea coast, or festivals and fora (like the World Youth Festival or Eurasia Global Forum), or the Russian Movement for Children and Youth (Movement of the First), or historical clubs and patriotic tourism movement sponsored by the Russian Society for Military History.

However, few of these initiatives are available to foreigners or export oriented. Most of the contests imply that the participants should have Russian citizenship – as a prerequisite for budgetary allocations to them due to tough regulations of the Ministry of Finance. Among the exceptions are the International Prize We are together and related forum for the volunteers from all over the world, the international track of the Leaders of Russia contest for medium-level and top managers (it grants Russian citizenship as a reward), different conferences of the Young Diplomats Council, Dobro.com international volunteer platform or bilateral fora and roundtables of the National Council of Youth and Children Organizations.

Rossotrudnichestvo implements the Young Generation program, bringing approximately 1.000 young people per annum (from journalists to engineers) to Russia to provide them with knowledge and new connections within their professional communities. Another initiative is aimed at 700 teenagers annually representing Russian diaspora who can upgrade their skills and get to know the places of interest in Russian regions within the Hello, Russia! program. Russian volunteers can travel abroad to train their peers and render assistance within the framework of the Missiya Dobro (Mission of Kindness) project. However, most of these activities lack rational and systematic follow-up work – the alumni communities are yet to be set up.

Ksenia Mineeva: What role can NGOs play in strengthening Russia’s soft power potential?

Dmitry Polikanov: Russian NGOs possess exclusive experience in tackling social issues and elaborating advanced social innovations although they have quite modest budgets. Nonetheless, so far most of the NGOs that are present in the international arena have been think tanks, friendship societies and various public diplomacy associations. Their major objective is to maintain communication; therefore they concentrate on organizing different roundtables, conferences, publications, and rituals such as the erection of monuments in commemoration of some events and personalities. This kind of activity is also quite popular with regional authorities and municipalities – they confine their international cooperation to such dialogues, mainly involving senior generation of activists. They regard as their key performance indicator the circulation of published books or the number of adopted resolutions instead of efficiency of communication – via community management, changing perceptions or growing media audiences.

Another problem is the lack of grant-making organizations in this sphere. While many countries use different foundations to maintain humanitarian cooperation, Russia does not have many tools to give grants, fellowships, or any other subsidies to its foreign partners in the NGO and media sector. The list of funds contains less than a dozen of organizations, most of which specialize at supporting Russian NGOs in their international efforts. Besides, even this funding is dispersed and frequently duplicates the projects. So, there is an urgent need for the concentration of resources (e.g., by the establishment of a single international grants fund) or better coordination of their distribution with clear division of labor.

It is important these days to create the opportunities for international cooperation for the Russian socially oriented NGOs – they have no connection with the alleged Russian propaganda, are open to the exchange of good practices and are capable of undertaking joint cross-country projects with foreign partners designated to help people in need. In 2022, Rossotrudnichestvo launched the Time of Kind Deeds project, which assists the delegations of Russian social NGOs to travel abroad and to meet their peers – be it the aid to the homeless animals or people with disabilities. Besides, a few educational courses were developed with partners in 2021-2023 to train the NGOs on the issues of international humanitarian cooperation and to support them in integrating these matters into their strategies.

Another form of engaging NGOs is the establishment of nongovernmental Russian Houses abroad. Rossotrudnichestvo announced this project in the fall of 2021[50]. It implies a framework agreement with an NGO or a business entity aimed at expanding Russia’s cultural presence outside capital cities (which host the majority of official Russian Houses) and to the new countries that lack inter-governmental agreements with Russia on the functioning of its official cultural centers. The most effective model combines the efforts of the pro-Russian business (or a representative office of the Russian corporation) and a group of activists (belonging to the community of compatriots or university alumni, for example) who can organize Russian language courses, hold different cultural and sports events and, hence, establish the point of contact for those who are interested in learning more about contemporary Russia.

Ksenia Mineeva: From your point of view, will the role of the Russian soft power change in the future? What reforms should be put in place to build Russia’s effective positioning abroad?

Dmitry Polikanov: It is worth noting that the role of Russian soft power will only increase in the future – Moscow needs efficient tools to promote its image in the modern world of turbulence and in the post-war reality. It is clear what should be done from the point of tactics, and it is practically impossible to optimize the system further. It requires radical investment and change to achieve a real breakthrough. There are no signs yet of the readiness of the key actors to conduct such reform – they continue to rely on organic growth in a number of events and duplicate activities without significant accumulation of funds for critical and purposeful efforts. However, if there is more coordination and strategic planning, even these modest contributions can make some difference. Russia deserves to have a soft power appropriate to its great power ambitions.

[1] Bami X. Even for Likes of Serbia, Putin’s Russia Now “Toxic” – Russian Journalist // Balkan Insight, August 30, 2023. URL: https://balkaninsight.com/2023/08/30/even-for-likes-of-serbia-putins-russia-now-toxic-russian-journalist/

[2] Brzezinski Z. The Grand Chessboard: American Primacy and Its Geostrategic Imperatives. New York: Basic Books, 1998.

[3] Russia is as Enfant Terrible. In the Eye of the “Others” // Baltic Worlds, January 21, 2014. URL: https://balticworlds.com/russia-as-enfant-terrible/

[4] You’re still Upper Volta with Rockets, Mr. Putin // The Times, June 30, 2019. URL: https://www.thetimes.co.uk/article/you-re-still-upper-volta-with-rockets-mr-putin-fdc7rqv7m

[5] The National Security Strategy of the Russian Federation, 2021 // Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations, July 2, 2021. URL: https://www.fao.org/faolex/results/details/en/c/LEX-FAOC203816/

[6] The Constitution of the Russian Federation, Article 72 // Government of Russia. URL: http://archive.government.ru/eng/gov/base/54.html

[7] Ильницкий, А., Лосев, А. Индуцированная деградация мира. Глобальные угрозы человечеству — что делать России // Парламентская газета (Москва), 26 августа 2023 г. URL: https://amicable.ru/news/2023/08/08/20380/degradation-as-west-strategy-in-mental-war/

[8] Указ Президента Российской Федерации от 05.09.2022 № 611 «Об утверждении Концепции гуманитарной политики Российской Федерации за рубежом» // Официальное опубликование правовых актов. URL: http://publication.pravo.gov.ru/Document/View/0001202209050019?index=2&rangeSize=1

[9] The Concept of the Foreign Policy of the Russian Federation, 2023 // Russian Foreign Ministry, March 31, 2023. URL: https://mid.ru/en/foreign_policy/fundamental_documents/1860586/

[10] Burkov V., Mescheryakov K., Shamgunov R. The Commonwealth of Independent States as a Way to a “Civilized Divorce” // Eurasian Integration: Economics, Law, Politics, 2016, №2, Pp. 63-70. URL: https://www.eijournal.ru/jour/article/view/81?locale=en_US

[11] The Concept of the Foreign Policy of the Russian Federation, 2023 // Russian Foreign Ministry, March 31, 2023. URL: https://mid.ru/en/foreign_policy/fundamental_documents/1860586/

[12] Valdai International Discussion Club Meeting // Official Website of the Russian President, October 5, 2023. URL: http://en.kremlin.ru/events/president/news/72444

[13] Advanced Military Technology in Russia // Chatham House, September 23, 2021.

URL: https://www.chathamhouse.org/2021/09/advanced-military-technology-russia/03-putins-super-weapons. Chatham House is included by Russia in the List of foreign and international nongovernmental organizations whose activities are recognized as undesirable on the territory of the Russian Federation – Editor’s Note.

[14] Musallimova R. Russia Seeks to Help Africa Transform into Influential Center of World Development, Ambassador Says // Sputnik.Africa, September 13, 2023. URL: https://en.sputniknews.africa/20230913/russia-seeks-to-transform-africa-into-influential-center-of-world-development-ambassador-says-1062087661.html

[15] MGIMO Centre for Sustainable Development and ESG Transformation Digest № 3 // MGIMO University, April 19, 2022. URL: https://english.mgimo.ru/news/mcur-digest-3

[16] Tolstukhina A. Russia’s Global Information Security Initiatives // Russian International Affairs Council, September 22, 2023. URL: https://russiancouncil.ru/en/analytics-and-comments/analytics/russia-s-global-information-security-initiatives/

[17] Article “Russophobia as a Malignant Tumor in the United States” for the Russian Newspaper “Rossiyskaya Gazeta” // Embassy of the Russian Federation to the USA, February 28, 2023. URL: https://washington.mid.ru/en/press-centre/news/russophobia_as_a_malignant_tumor_in_the_united_states_article_for_the_russian_newspaper_rossiyskaya_/

[18] Ильницкий, А., Лосев, А. Индуцированная деградация мира. Глобальные угрозы человечеству — что делать России // Парламентская газета, 26 августа 2023 г. URL: https://amicable.ru/news/2023/08/08/20380/degradation-as-west-strategy-in-mental-war/

[19] Ruscism // Wikipedia. URL: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ruscism

[20] Business Guide. Тематические приложение к газете «Коммерсантъ» № 8 // ИД Коммерсантъ, 22 мая 2023 г. URL: https://www.kommersant.ru/doc/5985985

[21] Фальков рассчитывает, что число иностранных студентов в вузах России не сократится // ТАСС, 27 апреля 2023 г. URL: https://tass.ru/obschestvo/17623459

[22] Kuzio T. Ukraine is Finally Freeing Itself from Centuries of Russian Imperialism // Atlantic Council, August 1, 2023. URL: https://www.atlanticcouncil.org/blogs/ukrainealert/ukraine-is-finally-freeing-itself-from-centuries-of-russian-imperialism/. Atlantic Council is included by Russia in the List of foreign and international nongovernmental organizations whose activities are recognized as undesirable on the territory of the Russian Federation – Editor’s Note.

[23] Исследования о русском языке // Eurasian Monitor, 21 октября 2022 г. URL: https://eurasiamonitor.org/news/zagholovok_stat_i0123456

[24] Индекс положения русского языка в мире, выпуск № 2, 2022 // Государственный институт русского языка имени А.С. Пушкина, 2022. URL: https://cis.minsk.by/img/news/24669/63bfff90826a3.pdf

[25] Токарев А. К великому будущему осторожными шагами // Российский совет по международным делам, 20 февраля 2023 г. URL: https://russiancouncil.ru/analytics-and-comments/analytics/k-velikomu-budushchemu-ostorozhnymi-shagami/

[26] Official Website of VCIOM. URL: https://wciom.com

[27] Global Peace Index 2022. Measuring Peace in a Complex World // Vision of Humanity, June 2022.

URL: https://www.visionofhumanity.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/06/GPI-2022-web.pdf

[28] Fagan M., Poushter J., Gubbala S. Large Shares See Russia and Putin in Negative Light, While Views of Zelenskyy More Mixed. Overall Opinion of Russia // Pew Research Center, July 10, 2023.

URL: https://www.pewresearch.org/global/2023/07/10/overall-opinion-of-russia/

[29] Davis E. Survey: Russia Rates Highest as a Threat to the World, Half See US as a Global Danger // US News & World Report, September 7, 2023. URL: https://www.usnews.com/news/best-countries/articles/2023-09-07/russia-rates-highest-as-threat-to-the-world-half-see-u-s-as-global-danger

[30] Игорь Ашманов о секретах производства «картинок с ужасными преступлениями русских» // Ukraina.ru, 13 сентября 2022 г. URL: https://ukraina.ru/20220913/1038688372.html

[31] Internet Censorship in Russia // Wikipedia. URL: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Internet_censorship_in_Russia

[32] Serhan Y. A New UN Vote Shows Russia Isn’t as Isolated as the West May Like to Think // Time, October 13, 2022. URL: https://time.com/6222005/un-vote-russia-ukraine-allies/

[33] Federal Law “On the Federal Budget for 2023 and for the Planning Period of 2024 and 2025” // ConsultantPlus, December 5, 2022. URL: https://www.consultant.ru/document/cons_doc_LAW_433298/

[34] Finansiering av biståndet // Sida. URL: https://www.sida.se/sa-fungerar-bistandet/finansiering

[35] Государственные программы // Правительство России. URL: http://government.ru/rugovclassifier/section/2649/

[36] Рустамова С. В МИД РФ появится департамент «мягкой силы» // News.ru, 31 октября 2022 г.

URL: https://news.ru/world/v-mid-rf-poyavitsya-departament-myagkoj-sily/

[37] Bort C. Why The Kremlin Lies: Understanding Its Loose Relationship with the Truth // Carnegie Endowment for International Peace, January 6, 2022. URL: https://carnegieendowment.org/2022/01/06/why-kremlin-lies-understanding-its-loose-relationship-with-truth-pub-86132. Carnegie Endowment for International Peace is included by the Russian Ministry of Justice to the register of foreign agents – Editor’s Note.

[38] Kling J., Toepfl F., Thurman N., Fletcher R. Mapping the Website and Mobile App Audiences of Russia’s Foreign Communication Outlets, RT and Sputnik, across 21 Countries // Harvard Kennedy School, December 22, 2022. URL: https://misinforeview.hks.harvard.edu/article/mapping-the-website-and-mobile-app-audiences-of-russias-foreign-communication-outlets-rt-and-sputnik-across-21-countries/

[39] Fox R. Ukraine Knows Winning the Information War Gives it the Edge on the Front Line // The Standard, November 23, 2022. URL: https://www.standard.co.uk/comment/ukraine-russia-war-information-vladimir-putin-twitter-elon-musk-volodymyr-zelensky-b1041997.html

[40] Russia: Bill Bans Work with Most Foreign Groups // Human Rights Watch, July 25, 2023.

URL: https://www.hrw.org/news/2023/07/25/russia-bill-bans-work-most-foreign-groups

[41] Володин предложил отправлять релокантов на рудники вместо Магадана // РБК, 11 октября 2023 г. URL: https://www.rbc.ru/rbcfreenews/652684219a79470e7640126c

[42] Чем больше детей, тем легче пожертвовать штампом о замужестве. Демограф объяснил, почему на Кавказе разводятся чаще // Фонтанка.ру, 30 июня 2023 г. URL: https://www.fontanka.ru/2023/06/30/72451745/

[43] Алиева К. Названы победители посвященной Шуше Олимпиады по русскому языку // Sputnik. Азербайджан, 3 июня 2022 г. URL: https://az.sputniknews.ru/20220603/nazvany-pobediteli-posvyaschennoy-shushe-olimpiady-po-russkomu-yazyku-442501217.html

[44] В Республике Индонезия начались занятия в Центре открытого образования на русском языке и обучения русскому языку // Минпросвещения России, 18 июля 2023 г. URL: https://edu.gov.ru/press/7304/v-respublike-indoneziya-nachalis-zanyatiya-v-centre-otkrytogo-obrazovaniya-na-russkom-yazyke-i-obucheniya-russkomu-yazyku

[45] В Таджикистане открылись пять школ с обучением на русском языке // Минпросвещения России, 1 сентября 2022 г. URL: https://edu.gov.ru/press/5711/v-tadzhikistane-otkrylis-pyat-shkol-s-obucheniem-na-russkom-yazyke/

[46] В Киргизии стартовало строительство русских школ // Вести, 1 сентября 2023 г. URL: https://www.vesti.ru/article/3530057

[47] «Послы русского языка в мире» // Государственный институт русского языка им. А.С. Пушкина. URL: https://www.pushkin.institute/projects/posly-russkogo-yazyka/

[48] Квота на обучение в РФ иностранцев выросла в полтора раза // Российская газета, 9 октября 2023 г. URL: https://rg.ru/2013/10/09/kvota-site-anons.html

[49] Бугулова И. На поддержку русских театров за рубежом направят 10 миллионов рублей // Российская газета, 7 апреля 2023 г. URL: https://rg.ru/2023/04/07/na-podderzhku-russkih-teatrov-za-rubezhom-napraviat-10-millionov-rublej.html

[50] Россотрудничество готовится открыть 20 «русских домов» в некоторых странах // ТАСС, 4 сентября 2021 г. URL: https://tass.ru/politika/12302683

The preparation of the interview was carried out for the Security Index Yearbook 2024/2025 Global Edition, elaborated in frames of the joint project of PIR Center and MGIMO University Global Security, Strategic Stability, and Arms Control under the auspices of the Priority-2030 Strategic Academic Leadership Program.

Key words: International security; Politics; Strategic stability

RUF

F4/SOR – 24/07/05